With and Without Diana

Mother speaks through daughter as daughter speaks to mother

How many times have I written about this project, privately, publicly, to friends, to family? I compare this project to everything I do and write about. I rest with this project when I attempt to articulate the unexplainable bonds within a collection of things. I use this project as a shield when I feel ashamed of my own archive fever. A project so beautiful, in so many ways it propelled the idea of Amurmur into me. In every way, it gives confidence and depth to everything I’ll be leaving behind. The best side of this project might just be the project leader, Rachelle Francis, an immeasurably treasured friend of mine. Specialness beyond my comprehension of the word, partly because she carries the memory of the distinctiveness of her late mother, Diana Francis.

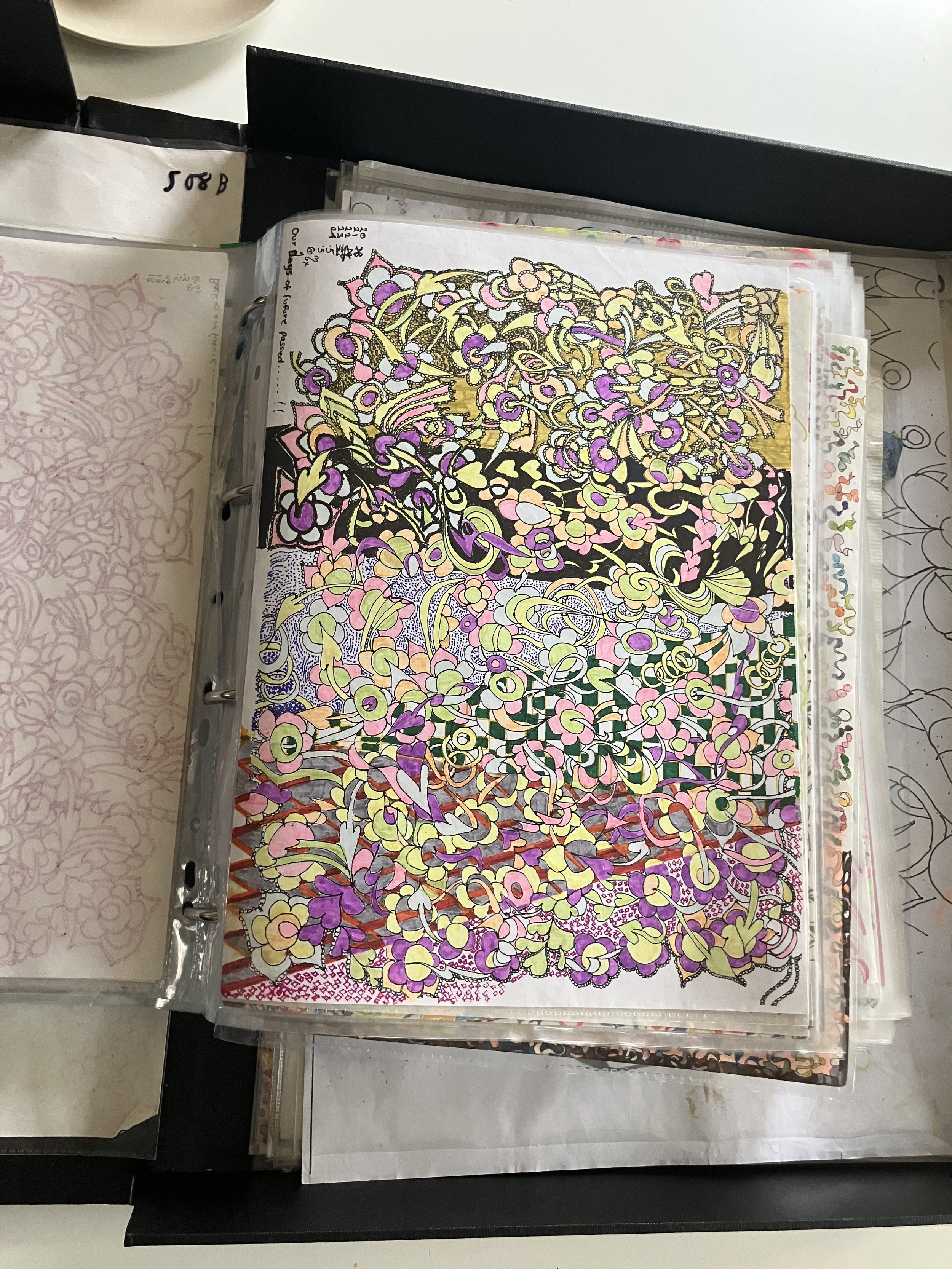

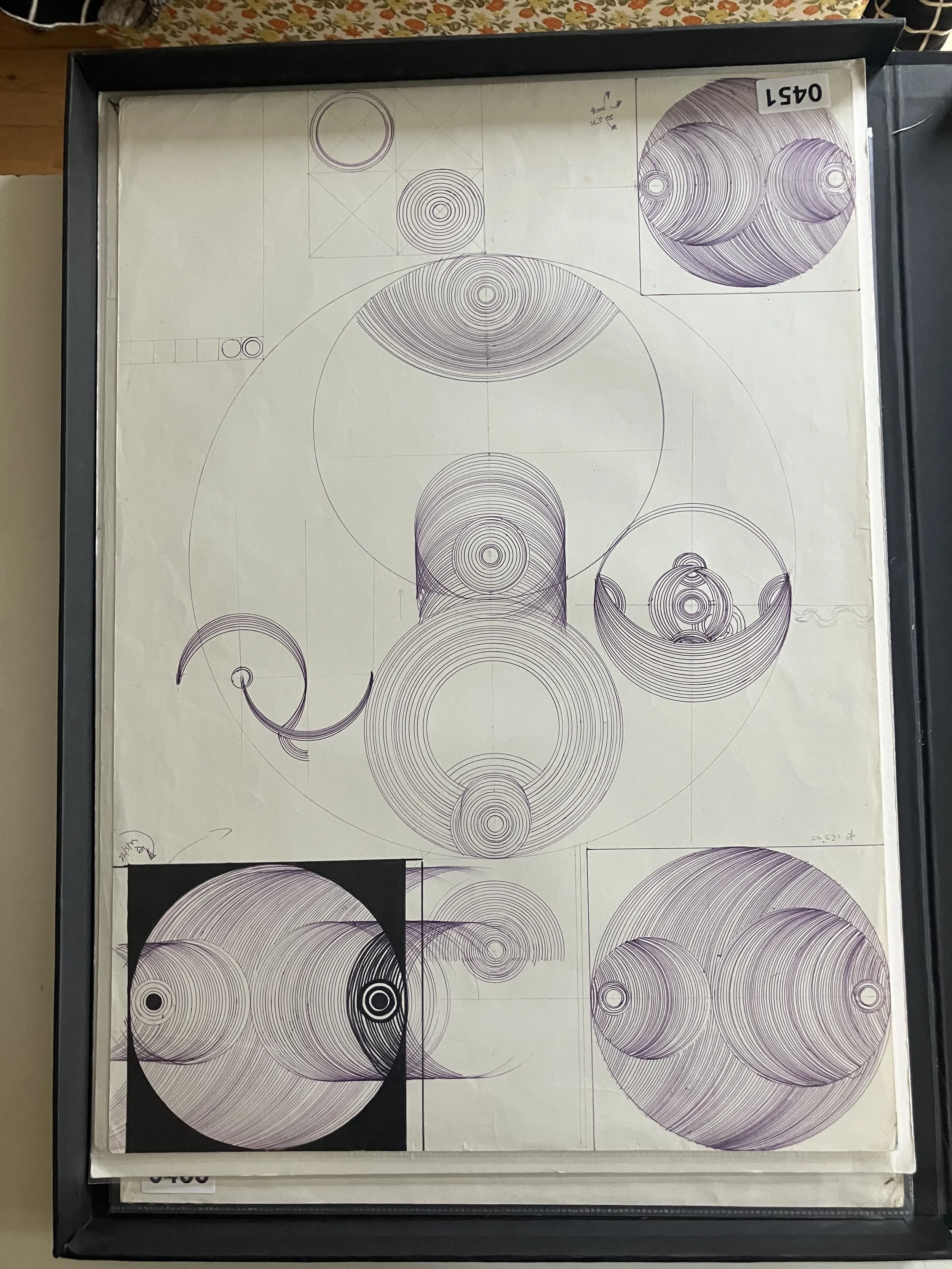

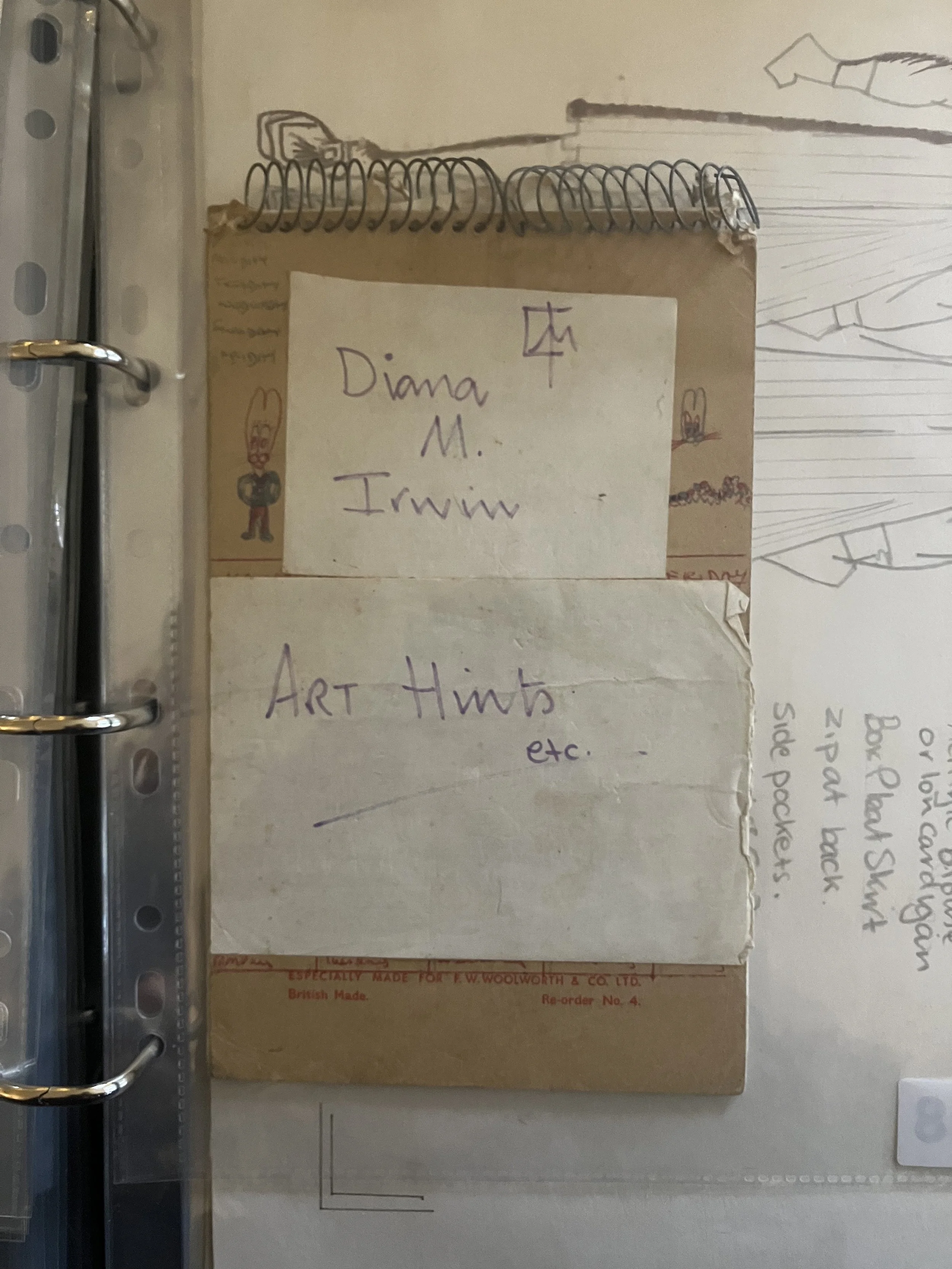

The Archive of Diana Francis, née Irwin - annotated by her daughter Rachelle.

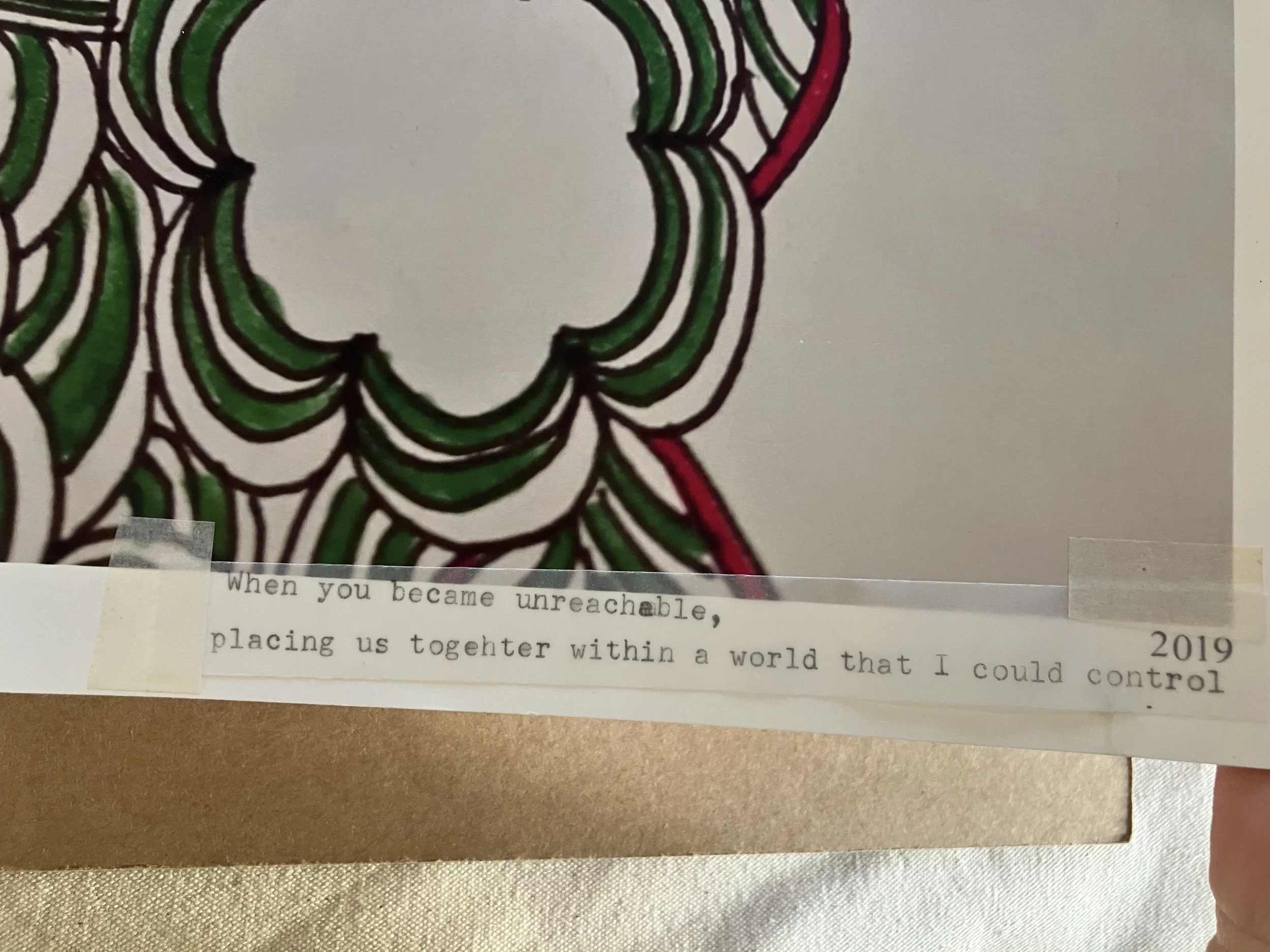

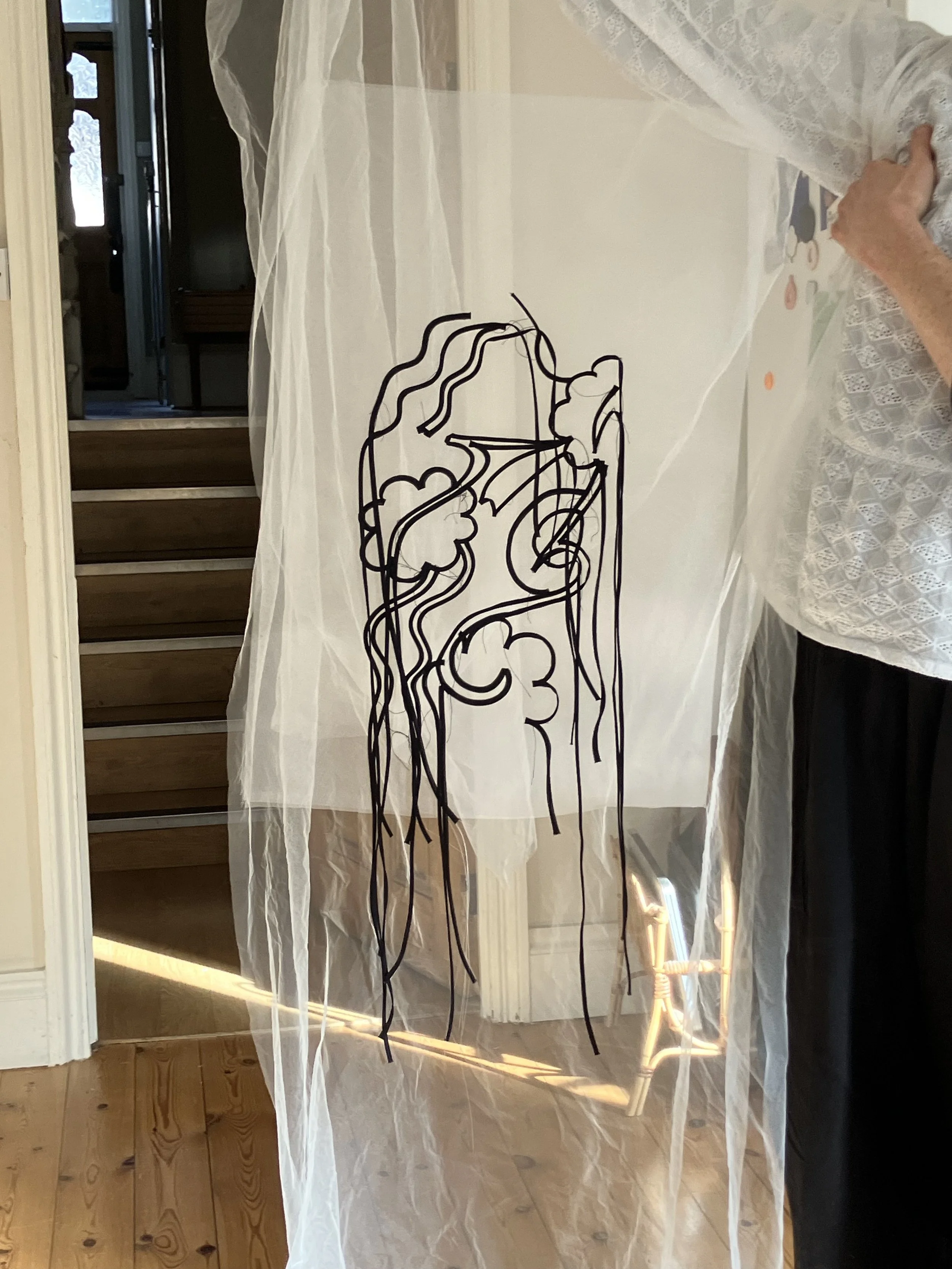

Picture embroidery and all the movement that led to it, all the feelings it contains. Think about the shapes and the fingers that shaped them. Imagine also what might contain the embroidery itself, the envelopment and the synaptic gestures that brought the contours to tangible form. Deliberate over the reasons behind who made the pattern. Remember who showed you the creation and encourage the person who arranged it into existence. Thank yourself, the one carrying it now. You, the person now outlining the new specks of life swimming inside the drawing that made the embroidery. This cocoon, this love and fascination that surrounds it, feel the presence within, with and without the embroidery and its shapes and all the ways it had to exist to become a shape. Did I say “with and without the embroidery”? Sorry, I meant to say “With and Without Diana.”

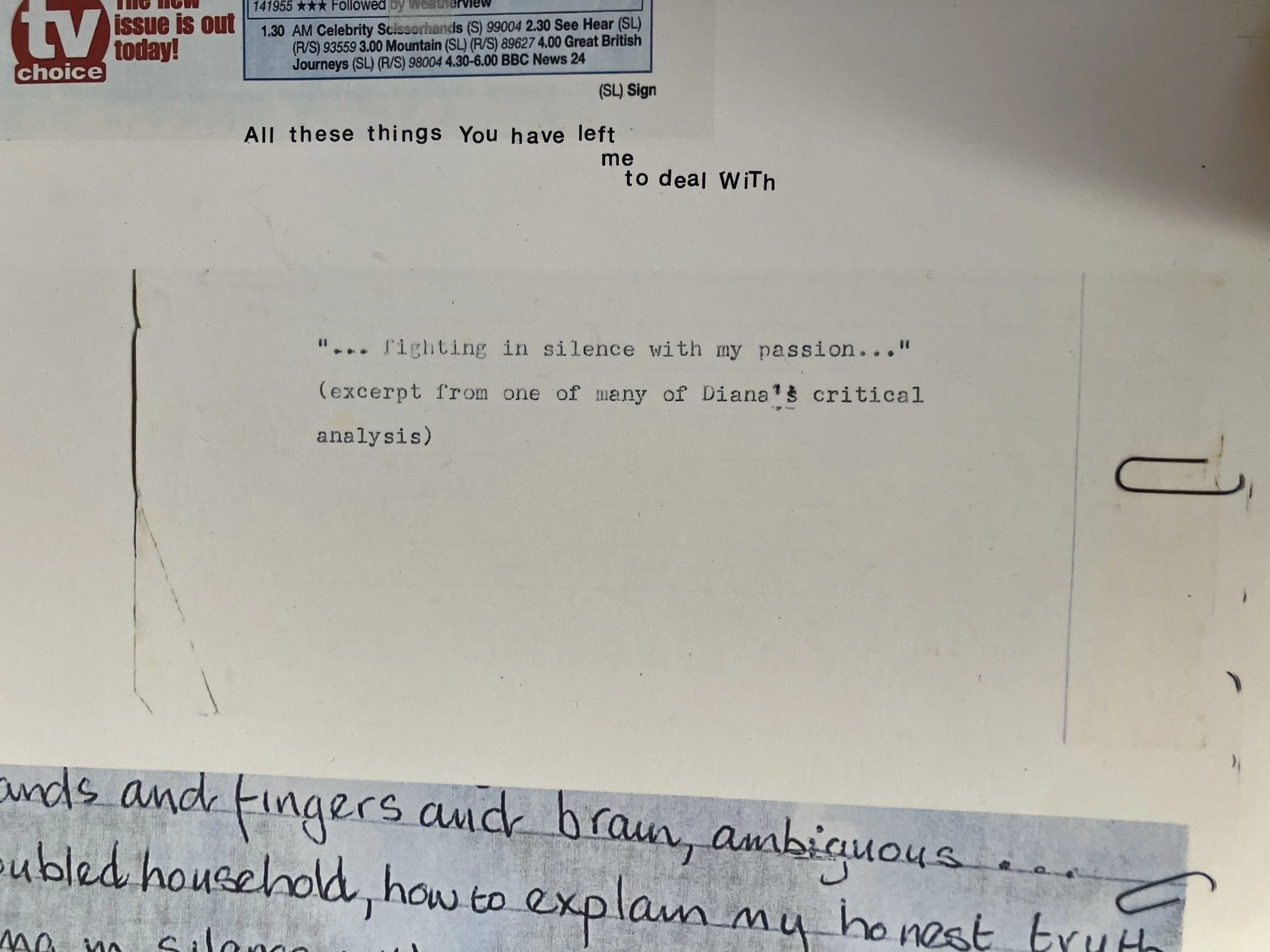

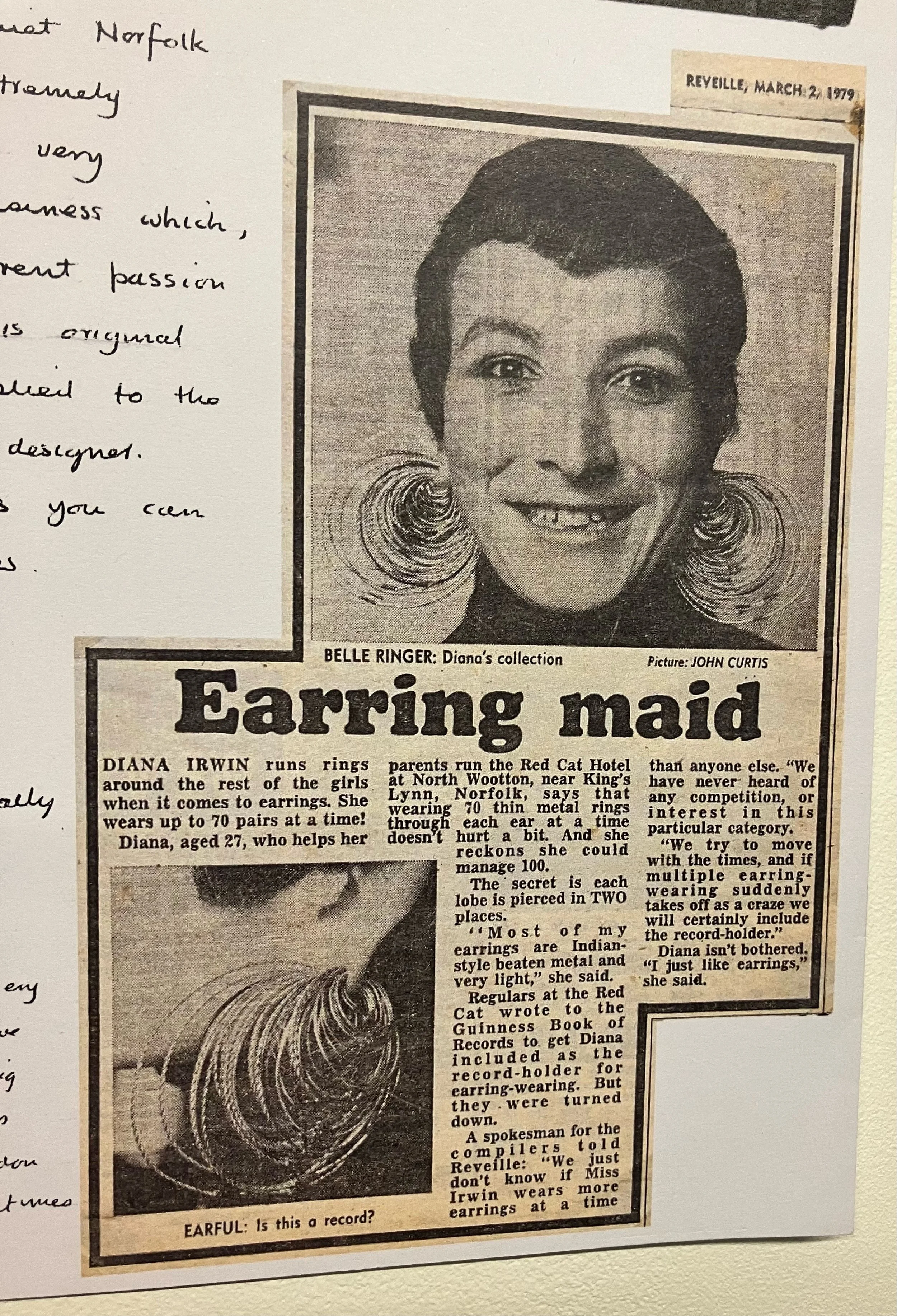

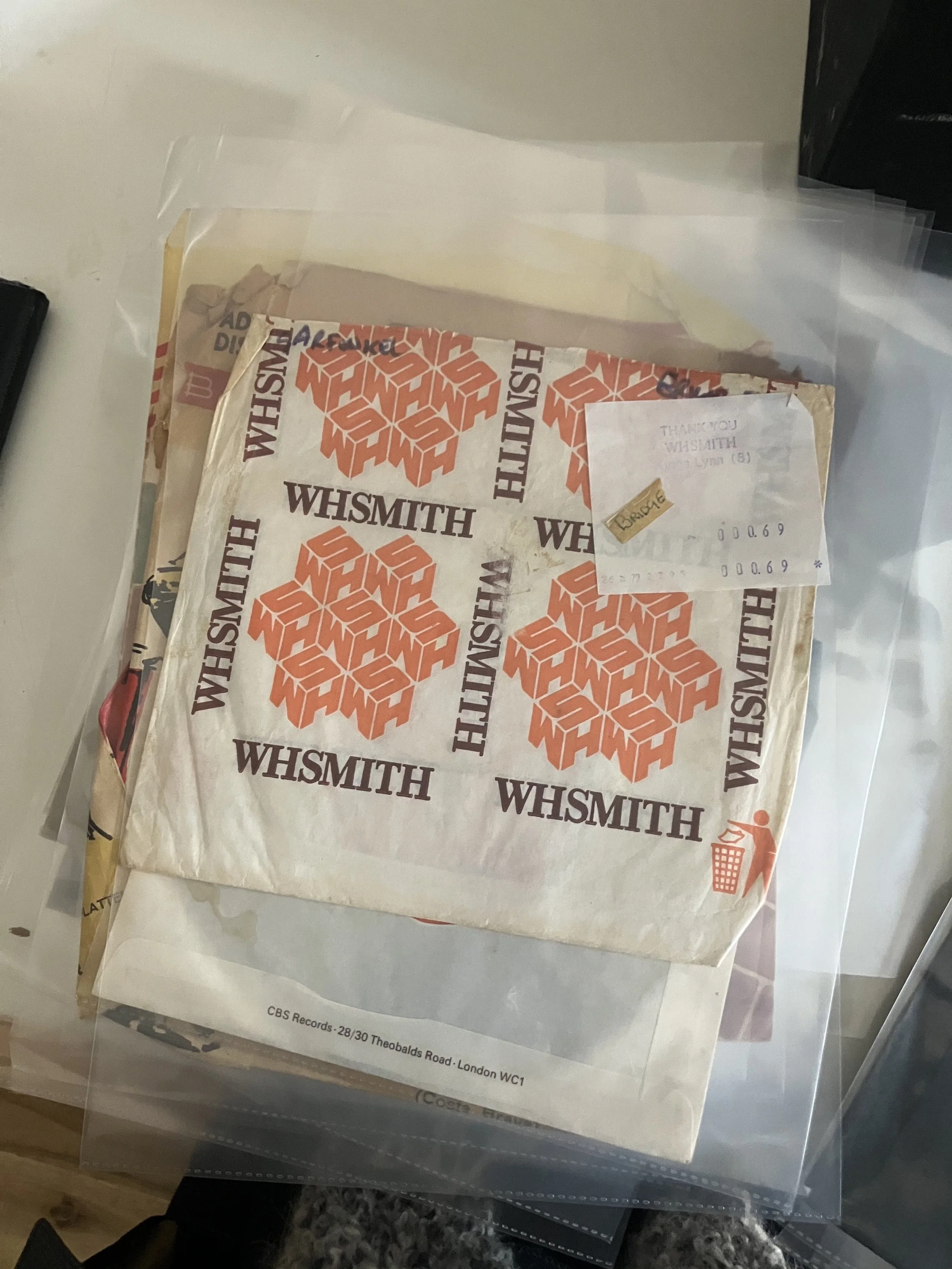

The bones of this project were growing before there even was a Rachelle. They began in a secret, soundless defiance, a protest against being misunderstood and unseen. Without guidance or accompaniment, a young girl with 75 hoop earrings in her ears began to draw. Her drawings elucidated her own mysteries, challenged the way humankind had misconstrued her. She gave herself the gift of respite: flowers, shapes, words and kindness that her surroundings weren’t offering her. Diana was drawing her own nature, trees and roots that carried the buds emanating from the skeleton of a singular mind. Doors of perception opening to herself only, where she could hide and smile and be the Diana she deserved to be. This young girl, the one with 75 hoop-earrings in her ears, the one who would change the covers of her record sleeves in a tender effort to understand them in her own way, was forced to grow up on shaking ground. She found reduced space in the world for her hastened drawings so made sure they remained hidden away. Theft during art college and a complicated marriage chipped away at the spirit she’d contained in a pen and pencil fortress. Addiction took over, a bubble self-administered against turmoil, because very few had reminded Diana how important the power of her drawings were. We’ll never know whether she chose to draw new nature because a garden grows, and from the sprouts, Rachelle was able to flourish dependant on her own weather. Plants change size, colour, grow cold and thirsty, regenerate when taken care of, spill onto other yards and back again, breathe, speak to each other and finally, they stay true to their roots. The flowers had sowed seeds, and the seeds grew into a daughter who knew exactly where to keep planting what mother had begun instinctively and meditatively gardening.

In her lifetime, Diana would show her drawings through the eyes of Rachelle, who constantly battled and encouraged a talent she always admired and recognised in her mother. I have countless recordings of my friend venturing through time, its early days apparent when she was just a child enamoured by her mother’s concealed drawings. This child lengthened their effect in an effort to want to hold the strength she perceived her mother was losing. In her adult life, overseeing the vast movement happening within the pen drawings, she began understanding doodling was Diana’s attempt to survive her past and present as “[an] abused confused child, to suicidal twenty-something, to romantic in love, to doting mother, to grieving mother, to anxious mother, to isolated adult, to depressed adult, to mature student artist, to addict and absent mother/grandmother, to isolated adult, to terminally ill.” Why do we hide? How do we conceal the things we hide within us? What does it mean when someone un-hides you but only once you’re not around anymore, no longer of-earth asking to be hidden? Why does one yearn to “unquieten” things hidden?

“I’m looking for signs, all the time. I’m so scared, all the time.” We laugh when Rachelle says this as we sit, in our time warp, imagining an unwanted pair of ears misinterpreting this kind woman speaking of a ghost, spectral and scary. This project courts haunting, yes, but of a kind and soft nature: Rachelle speaks of the spirit of what she wishes to repair, a story that took a turn it never should have. Rachelle yearns to redeem all the truths of her beloved mother and speak to her through Diana’s belongings. Through the movement of her twirling hands comes a continuation of the sighs of her mother. Rachelle adds magic and love to her motion as a staunch believer in this textile based remix. A joyous peace at an evolving pace. A lucid and bending collage of three truths that learned to exist with each other: the Diana in tragedy, a Rachelle enamoured with Diana despite sad punctuation marks in the flow of her life and the Rachelle of today, “looking for signs, all the time. Scared, all the time.” So Rachelle took to bringing to 3D the 5D worlds Diana could imagine within the confines of her eyeballs and produce on a 2D surface. The lands within Diana grew tails and who better than her own child to render these to new life using the bonding and healing movement of needle and thread. Rachelle has curated an exhibition of her mother’s work combined with her own, put together myriad workshops with charities, all inspired by the girl with 75 hoops in her ears, offers one-on-one sessions with patients suffering from Dementia or other obstacles of the mind and has them interact with shape, published a mindful doodling activity book also inspired by her mother now sold in the Wellcome Collection, produced an upcoming documentary about the project, is in the throes securing a final resting space for Diana’s archive of work in an institution and is working towards an exhibition showcasing the way Diana has inspired many. Whichever form creativity takes, Rachelle finds herself chatting and exchanging with her mother, with herself about her mother, or simply for her mother. Thread is their unbreakable umbilical chord, the one repairing and mending, moving alongside time lost. After all, from repetition comes understanding. Diana left clues of herself by replicating shapes many times over and her daughter’s reprise of the duplication testifies for the most potent comprehension.

The colours of the flowers melt in and out of our minds and this started with Diana. Finger tip to finger tip the two women saw their steps accelerating and rebelliousness sparked out within each of their worlds. With Mum the insubordination was an alternative way of understanding and seeing, one less palatable to the living world but producing paper results filling the dreams of her little girl. Rachelle's rebellion lies in kindness, the slow reconciling with her mother’s ebbs and flows, and the staunch belief in the certainty of individuality and its tangled branches. Rebellion means following a feeling regardless of the constricting equations one has to solve in order to get to peace. My friend is a gentle renegade: with her, thanks to her, and through her, the faith she had in her mother has been transferred onto the work she does on a social level. She believes in all of us. I’ve been to one of Rachelle’s workshops, privy to the encouragement, cheered to move and exist in harmony with the material and tools of myself. I’ve been pushed to free what Diana had to silence and I’ve been acclaimed for my choices. I remember feeling embarrassed by the ugly emanating from what I produced and a cackling Rachelle reminded me “What does ugly even mean if it made you feel good?” We select a drawing by Diana and added our own landscapes to the bones of her imagination. Somehow we find ourselves collaborating with the breath of someone. Someone unconfident in her time who whispers her whole entire originality onto you. Attending the fruit of this glittering collaboration as a workshop is a rarity and a gift, one filled with care and compassion. An afternoon that sits with you and accompanies you whenever you next find yourself in despair.

This is a time-capsule allowing a posthumous pairing because the Francis girls spoke their own language. Today it is held high, forever celebrating the humanity of the dreamscapes and the varied figures that beauty can take. Creators without their Rachelle, where do their lovely flowers go? and who will speak to their swirls if the magic of these shapes have no conversation?

This project and its selfless ways makes me wonder about all the casualties of “otherness.” All those who didn’t have a preventative dictionary granted to them to help them navigate their fears or understand the outlines of their convictions so they could have seen and felt how beautiful their thoughts were. I like to imagine Diana knows just how much encountering her in paper form uplifts. I’m persuaded she knows that getting to know her, sides good or bad, through the eyes and thread of her doting daughter shifts something within. If I find myself cursed with the irritant feeling of inadequacy, or slightly mishandling my judgement in regards to the beat of someone else’s drum, I remind myself that they too, are planting the beginnings of their very own embroidery. I hope we all find a friend, a daughter, an archivist, a teacher and a gardener exactly like Rachelle Francis. The Rachelle with and without Diana.

All images are photographs of the archives of Diana and Rachelle Francis.words: Alexia Marmara, based on hours and hours of conversation and recordings of Rachelle Francis