An Ascertainable Eternal Time

The landscapes of Sabin and Tudor Bălașa

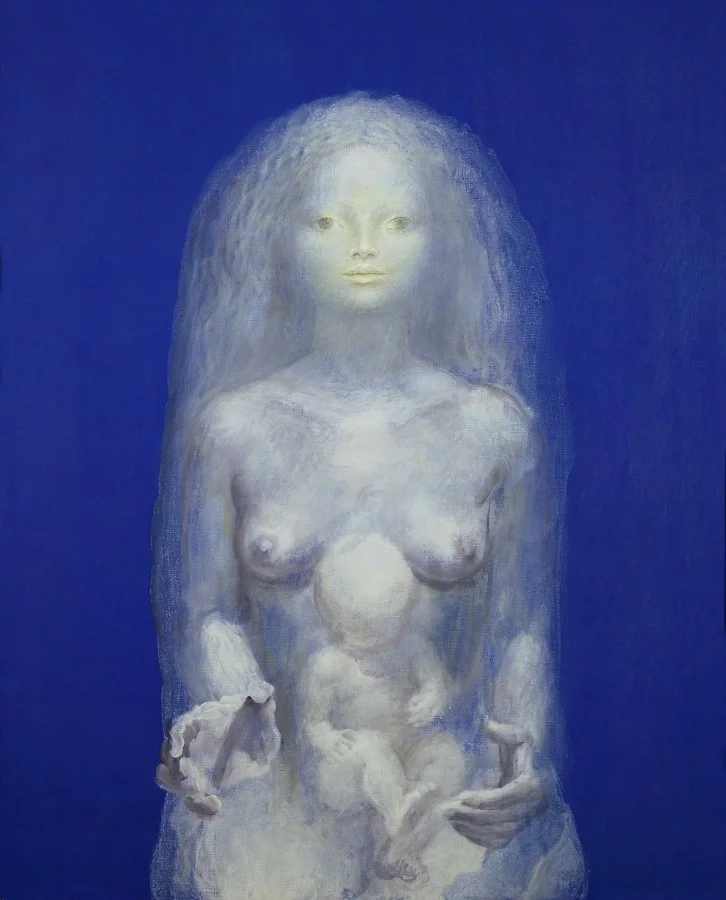

Sabin Bălașa Motherhood

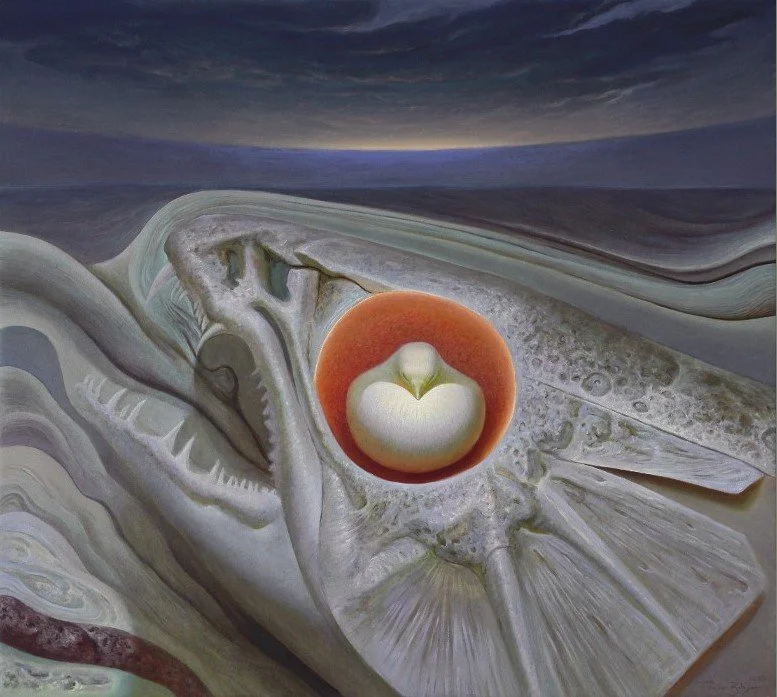

“How does your head look to your eyes? Well, I'll tell you. It looks like what you see out in front of you. Because all that you see out in front of you is how you feel inside your head.” These are the words of Alan Watts (The World as Emptiness II, Part 6: Consider Death Now.) To someone well-acquainted with - or freshly introduced to - the work of Romanian artist, painter, muralist, poet, animator and writer Sabin Bălașa (1932-2008) these words could also nod to the description of the process that released the beauty of the blue hues that follow us even after the quickest glance. Sabin Bălașa described his work as belonging to Cosmic Romanticism. The word cosmic in itself suggests vastness, a cluster of concepts beyond earth and time and a rebellious travel through universal laws. Whichever words critics and historians have used to describe him or the effect of his work, they always hark back to the depths of what lives inside his head or rather, what his mind was able to reach. They speak of the way it stored diverging knowledge inside an undulating brain to then digest it, understand it and lastly, present it. How strange it is, then, that I came to know of the work of this golden artist through a coincidental purchase of 1982 Romanian postage-stamps that feature his paintings. Is this what Bălașa does? Did what he saw inside his head help him travel beyond our logical understanding of time? Did his eyes reach ours by his own disobedient world-mail system? In the words of Mircea Deac, in his living and still today, Bălașa aspired to “an ascertainable eternal time.”

“Art is an individual message addressed to the collective. I live in the abyss and paint what I see with my mind; for me, art is a vision, an act of generosity, a supreme exercise of personal freedom, a great capacity to love.” - Sabin Bălașa

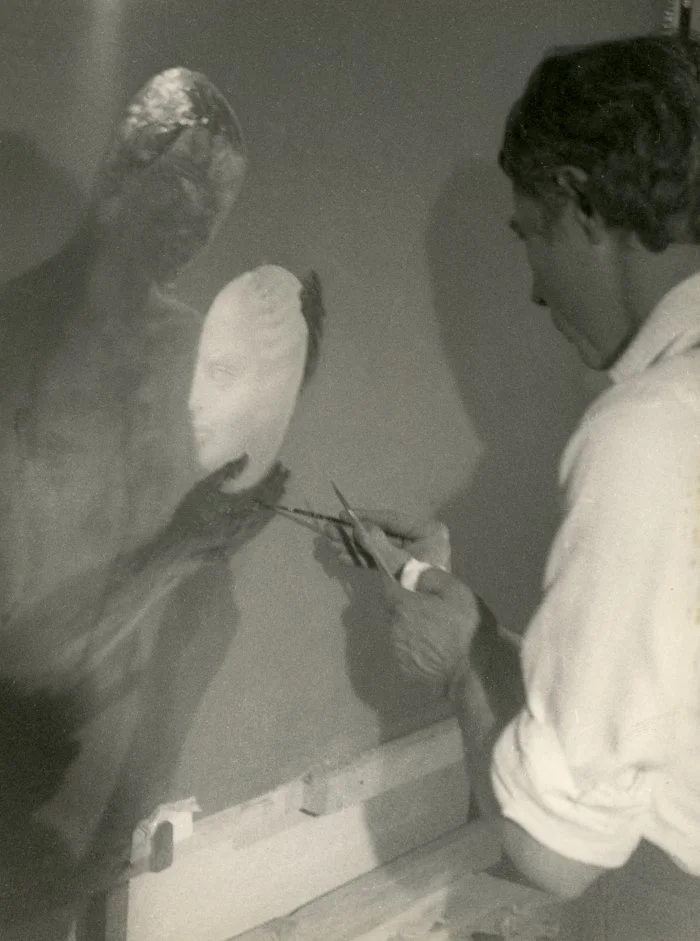

(Tudor Bălașa, Sabin Bălașa 1932-2008)

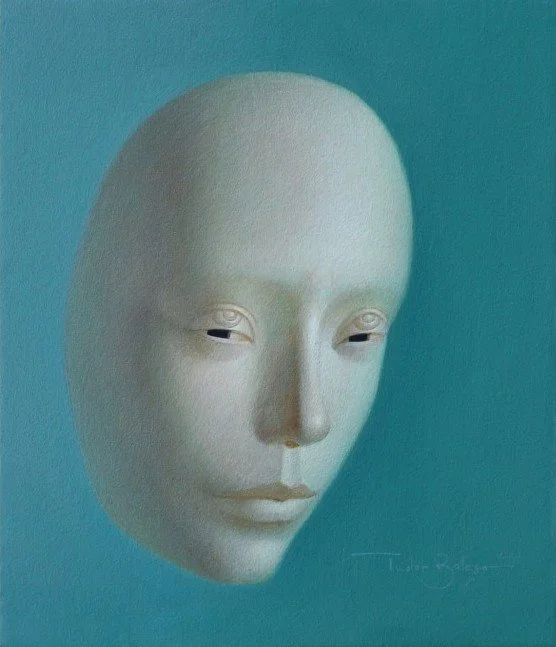

Tudor Bălașa The Painted Mask

Sabin Bălașa painting Galaxy

Discovering Bălașa and each of his “charming oddities” (Mirea Deac, Sabin Bălașa. 1984) cements the existence of parallel worlds and the theoretical thrills escaping the laws of science. Freedom found in pulsating colour and illusions speak of the regeneration of life. The viewer knows to trust in the forces that exceed the limits of coherence and reason. A few moments with Bălașa introduce us to the geological explorations of a future very much within the reach of our imagination… but only if we let them reach us.

“You realize that his hand was not made to occupy itself with anything else in this world. Bălaşa hunts and devours the model. He touches with his gaze all the silences and distances of the model. He gradually ignites the spiritual lights within it. He paints with all his strength, as one runs with all one’s strength. The studio fills with a suffocating tension. You witness something so intimate that you feel indecent seeing the artist elevate the work patiently […] He constantly controls the work, [...] moving his torso left and right, head tilted back, thus inspecting the resurrection of the work. His mouth twists continually, moved by who knows what impressions. He is charged with a great and perceptible power, a contained active force, when he paints. And with a natural pride, with a pure and fiery momentum.”

(Romulus Balaban, Români celebri, 1979)

Sabin Bălașa Solitude

Born the 17th June 1932, Sabin Bălașa spent his entire career stretching and bending clocks, joining the dots between philosophy and personal intuition, extending his personal mythology onto murals in public places, receiving awards for the lucid sways of his paintbrushes and creating animations deemed controversial as ahead of their time. His curriculum vitae bursts. He left behind a few murals around his home country, some in universities, another in a what today functions as a Radisson Blu Hotel. His animations are continually referenced and marvelled at. He exhibited in an extensive list of cities and countries, including Cairo, Alexandria, Torino, Cuba, Japan, Finland and wrote a constellation of novels, The Blue Desert (1996) The Exodus Towards the Light (2002) and Democracy in Mirrors (2006.) He relentlessly fought for his emancipation and “opposed mirages, falsity and oppressions. He did not have a partisan political opposition or advocacy, his concerns had a humanistic perspective.” (Tudor Bălașa) He never succumbed and never swayed, he was just like his work: indomitable.

“Everyting we imagine exists somewhere in infinity. There is also what we have not imagined.”

Sabin Bălașa

Tudor Bălașa Anima

A moment with paintings such as Nymph’s Play, or The King’s Daughter or Thoughts, helps one understand his “pursuit of [the] restless and what it looks like,” his painting of “a refuge in which the combustion of man with the universe can be shaped according to his thoughts.” (Mircea Deac, Sabin Bălașa. 1984) Creatures conjured and moulded appear silent, dynamic and free in their muteness. A belief in the static nature of humanity quickly disappears. A few moments later, the viewers find themselves confused again, longing for the vigor emanating from the paintings. One looks for him through his animation this time. The images gather together as stories unfold, unwind and unhinge things gone numb. Like the creator of these animations, the watchers find themselves gazing at humanity, questioning tyranny and challenging oppression. The cycle continues as we continually yearn for all the lessons that radiate from his distinctive work and crave the continual opportunity to rest in these other dimensions. Emphasized, of course, by the lack of precise dates on most of his work.

Sabin Bălașa The King’s Daughter

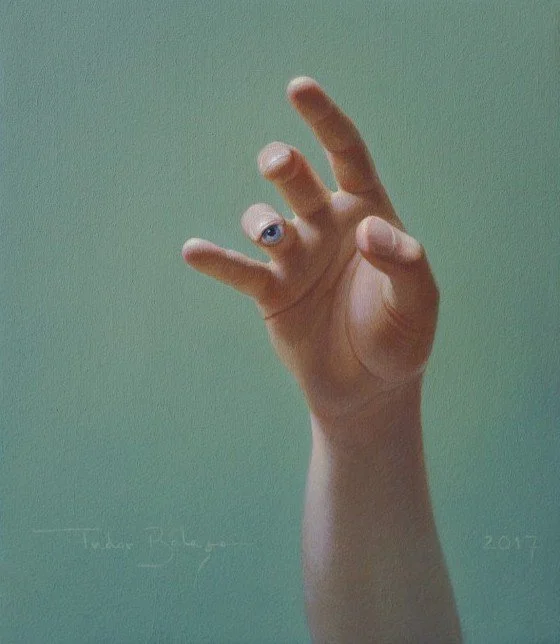

His son, Tudor Bălașa, is a painter too. His scenes speak of his own eyes, of a mind that reached his hands, as seen in Study of Painter's Hand (2017.) “My creations are metaphors that are evocative of my wonder about the mysteries of existence and reflective of my comprehension.” As father was always “looking forward not backward,” (Tudor Bălașa) son assumed the responsibility of the writing of an album: a collection of memories, photographs, writings and artworks that Sabin had begun putting together. “This album was meant to be put together by him alone; this text was meant to be written by him. For that is how he lived and created: alone before the world. He believed he would have all the time necessary to complete this project, and I now take upon myself the role of not contradicting him in any way, of granting him the time he believed to be eternal.” (Tudor Bălașa, Sabin Bălașa 1932-2008)

With the beauty and fluidity of both their rhythmical writings comes a greater grasp of the constant questions that animate their offerings: whether separately or together, theirs is a movement of grace and a celebration of infinite possibilities. Our own comfort in chronology is dismantled as Tudor takes the halted hand of Sabin and meanders with it through his father’s childhood, “in the village of Dobriceni, Olt County, into a family belonging to the rural intellectuals and thinkers educated in veneration of universal values ‘with Oltenian particularities,’ as he used to say with a smile.” The reader is acquainted with his hopes and fears as a child, with his son’s understanding of his father’s spiritual mother, his aunt Florica. “She was the seed that opened the locks of the mythological universe for Sabin. She mediated his access to the unseen world that later shaped and transformed him: the world of Oltenian fairy tales, of the forces and beings of earth and light, the boundless world of the universe.” (Tudor Bălașa, Sabin Bălașa 1932-2008)

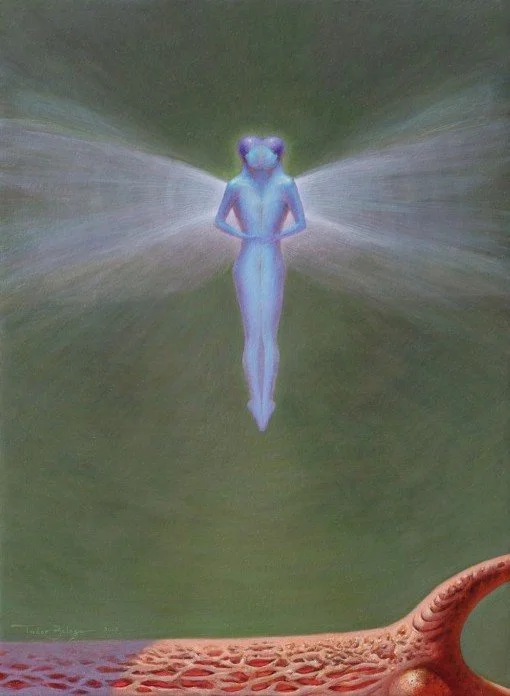

Tudor Bălașa Dragonfly

painting by Sabin Bălașa

Interrupting Tudor’s understanding of the things that shaped his father, we read Sabin’s lucid thoughts, childhood stories and feelings that educate us on the paths, hard or softer, that shaped the artist. The experiences that left a mark on Sabin, recorded by father and retold by son, show us the hardships of being surrounded by political silencing and imprisonment. In Sabin’s own words, “There exists within me the capacity to transmit the feeling of joy, and the hardships of life cannot diminish it.” (Tudor Bălașa, Sabin Bălașa 1932-2008) It also shows the power of revolutionary existence: wherever the struggle, the Bălașa way was to open difficulty to new possibilities by facing it, questioning it and reconceiving the outcome. Celebrated or vilified for it, onwards he moved even if girdled by unrest as his luminous hope was embalmed within his creative process.

For a mind that knows how to discern in harmony with the soul, the message of art appears clearly, eternally human. Despite historical amputations, it transcends the themes imposed by the politics of different eras, remaining detached from them. The message flashes instantly back to its source: the creator of the work. The individual power, will, and sensitivity of the artist come alive in the soul of the sensitive viewer. This does not happen without consequences. Those moved by art recognize a great artist to the extent that his art produces in them desired and lasting transformations.

(Tudor Bălașa, Sabin Bălașa 1932-2008)

Sabin Bălașa The Drop

In a final attempt to cage strange lands, I spoke to Tudor. Through meandering thoughts and discussions over my understanding of father and son (or rather, my misunderstanding…) the separate and conjoined immensity of their work and perception intensified. Both Bălașas hold onto the firm understanding that impressions are seeds. Their deliverance offers a humanist explanation of the ways the universe chooses to unfold around its subjects. I see clearly now, that the only inevitability in existence is the beauty of laying in the uncertain, refusing to let it settle.

Tudor Bălașa Study of a Painter’s Hand

Tudor Bălașa The Nest

Sabin Bălașa Fantastic Landscape

If I have learned anything, I have learned it only from the greatest artists in the world—and not from their painting; I learned something else, namely how not to imitate, to be equally free, personal, nonconformist, and unfettered as they were.

- Sabin Bălașa

Can you describe your father in a few words?

Sabin possessed a core of high sensibility with some inclinations towards an idealized romantic disposition, and all his other qualities and features deliberately subordinate to it. He was highly energetic and tenacious and he spent most of his life painting at his easel, but when among other people he was very social. He always grabbed the attention and very easily created polarized positions around him. He had a volcanic temperament that he educated with age managing to use it mostly to his own advantage. He used to assert his opinions like they were axiomatic deductions of the universal laws, so he wasn’t exactly a great diplomat, yet he successfully managed to navigate difficult times, always walking on the edge, being unpredictable in his actions and being always ready to quit and try something else rather than to allow anyone to have authority over him. He wasn’t by any means claiming to be perfect, nor did he seek perfection in his work but, instead, from an emotional perspective, he sought beauty and reason.

Sabin in his studio, 1984

In your own words, how would you describe his worlds?

Embracing humanity. Energizing, positively charged towards life and uplifting. Spiritual, emotional and mysterious, coherent, recognizable and impossible to forget. These are just a few words that rushed to my mind., not describing the work, but referring to it. I would not really favor the use of language to depict/describe painting, as its purpose is to be experienced visually. Maybe, only if a poet does it as a necessity, for the use of the blind.

Do you have memories of him painting, what was it like to watch him work and create?

It was a live demonstration of the thinking behind an intuitive and emotional process. He was all into action, immediately materializing each and every thought on the canvas. Sometimes he would change his mind again and again, in a matter of seconds and the metamorphosis on the canvas would build up as a layered record of his actions. Other times he would work for hours in one focused direction until the apparent completion, only to abruptly destroy most of the painting with a quick gesture in order to make room for a new intention that was about to emerge. His great skill allowed him to work extremely fast thus making effective this otherwise meandering process.

Your father is famous for his animation work too, can you explain how this came about?

He was always fascinated by the medium but lacked the possibilities. In fact, during most of the soviet rule, Sabin lacked all the possibilities, as from 1959 he was officially stigmatized due to his father being imprisoned for political reasons. In 1964, following a declaration of independence from the soviet influence, the Romanian state released all the remaining political prisoners and a period of cultural cooperation with the west began as a result of the policy of de-satellization from the soviets. At least by law, Sabin was no longer regarded as persona non grata, and a window of opportunity was opening: in 1966, the poet Marin Sorescu who was a friend of Sabin’s was working at Animafilm (the state owned and only Romanian animation studio) and he invited Sabin to create a short film based on his script. This was The Drop, Sabin’s first animation. Being internationally awarded in the same year, he was able to create more animation films, this time based on his scripts too, gaining more attention and recognition with each one. At some point he drew too much attention and he was stopped, against his will, as the cultural policy was shifting again. After the fall of the iron curtain, Sabin was contemplating the idea that later in life he would make a new one, this time a full-length film that he would independently produce, as the technology was becoming affordable, but he didn’t live long enough to do it.

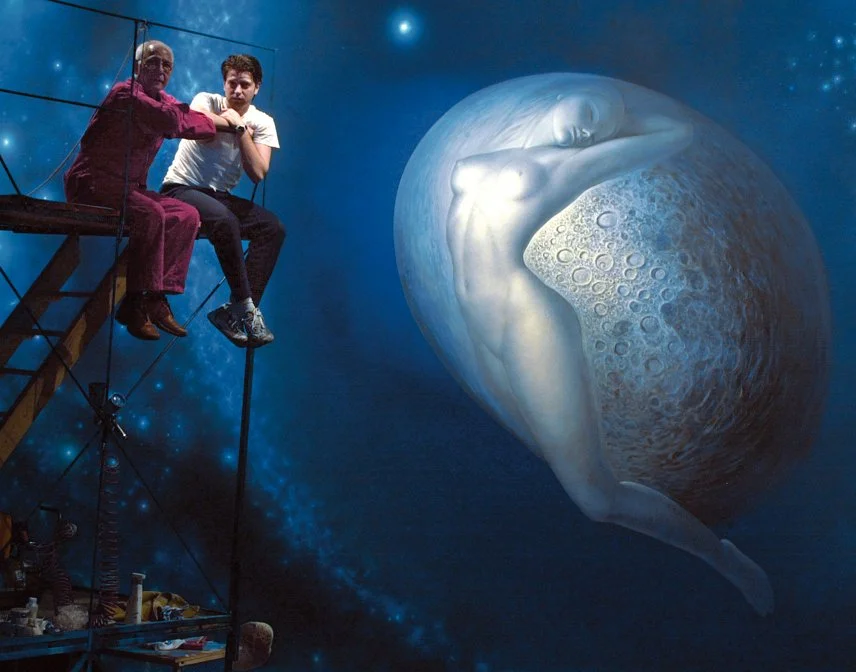

Father and son, Galaxy of Love

How successful was he in his living, and have you witnessed a change in the present?

Highly successful and very popular, not as much due to the formal international and national recognition which reached competent, but limited circles, but especially due to the continuous accumulation of exposure to the general population through his murals in public places and his animated films. His active personality which was either loved or hated, was also a contribution. Obviously, the iron curtain did not help, nor the official cultural policies, as they support a completely different artistic direction to his. As for the present change, only the obvious; he was alive and then he was dead. So, no more new artwork and whatever personal influence he had exerted on his success, these all ceased, naturally.

Apart from that, I notice that his art continues to create the same strong and positive response from most people, just as when he was alive. For now, his success is still being limited mostly by the extent that the general public discovers that Sabin’s art exists. As an example, the latest public presentation of his films took place in Los Angeles recently in a theater and I was informed that the tickets sold out well before the screening and that it was very well received by an audience in first contact with his art. Sabin’s work cannot change, but people continuously are. Maybe it is already received differently by younger generations. By comparison with people’s response to Sabin’s films from 30 years ago, many of today’s YouTube comments are different in content. They describe an interest emerging from an emotional connection but, often, also a confused relatedness to general themes of the world and humanity.

In that respect, was it through your father that you discovered your love for painting?

No, I was doing it first, he came only after. As it happens, I have memories from early on so I remember how it unfolded. I recall myself scribbling before I spoke simple words, very actively drawing and painting from before. Only later did I realise that my father also had the same habit. At that age, being so exalted, I was seeing my works as sublime, I didn’t mind his. I also assumed that this was what we all usually do. It was a revelation, when I fully understood and accepted that the reality and how I saw it are different things. Since then, I always keep this in mind when I think about reality.

What are the main reasons why you also paint?

I love it, all the rest derives from that. If I should interpret your question in the direction of me painting because my father, Sabin, was a painter too: I grew up surrounded by Sabin’s paintings, shelves of art books and lots of painting materials. My attraction for painting remained predominant and the only constant among all other interests that I took. That allowed me to have the perseverance to pursue it in the detriment of other possible outcomes. And I had a great art teacher at my disposal, for free. To me, all the art that is known are teachers/lessons to learn from, including Sabin. The obvious predetermination of my entire biographical constellation was so striking, that later in life I felt compelled to look into it, in order to observe where I lay as a factor in this equation. I changed and realigned my view on many things, but my preference for painting remained unchallenged. So, it is my choice even from this perspective, after all.

Sabin Bălașa Chimera

How has your father’s world shaped you?

I can only tell of how he was trying to shape me, what were his actions/intentions… Well, he tried his best not to directly interfere in any way. That was very considerate of him and quite fortunate for me, given that, sometimes, having his example was already enough. As a parent, he preached the highest respect for individual freedom, I was very loose as a child. He had an open, supportive and equidistant position towards all the interests that I manifested, without showing particularly favoring any of my activities. He sent me to a regular school, not an art school, and he didn’t voluntarily offer any suggestions, indications or advice of any kind on painting and drawing until I specifically asked him to teach me. I was already 17 years old when I came up with this request. He started by dividing painting in two parts, nicknaming one “No.1-what you want to do” and the other “No.2-how No.1 can be done”, he taught only the latter, leaving the first to my own freewill and discretion. His teaching style was that I was not to lose track of my own intentions, during and because of the difficulties related to the learning process, so both should go together. It was a very interactive way of learning and I had the luxury of being the only apprentice.

Your paintings evoke spiritual states, mystery and altered-consciousness, are these themes you look at in your day to day?

My general views are very broad. I don’t have any generic preconceived ideas or taboos about what art should or should not approach as a subject. I believe that each artist is entitled to construct his artistic universe with its own logic. Assuming that others value freedom as well, I find it most preferable if they should be able to control their medium so completely that they can bend, exaggerate, or suppress its conventions without losing coherence. This includes not only the art materials and artistic skills but also the language and the aesthetics of art. To narrow it down even more and answer your question, yes, it is my natural disposition, regardless of what I look at from the ordinary world, to very quickly realize that I exceeded the limit of my comprehension and that I find myself gazing into a mystery and a wonder. My interest is not just to stare into the reverie, but to actively interact, to extract some sense out of it and, hopefully, to grow from that effort. I also have this urge to build objects with my own hands. To make a material object that represents more than the sum of its constituting parts, has both a physical and a spiritual dimension. This suits both of my needs and keeps me balanced. Spiritual states vs. material world- I find the exterior life is of no less importance than the inner life. If I were not to inspect any of these aspects of my existence, I would suffer. My paintings are means through which I organize my thoughts, feelings and intuitions. It can be done also by many other means. The basic idea is to arrange them in various intentional ways, until when you look at them from a distance it helps you to understand more, as people say “to see the bigger picture”. When it happens that the real theme(s) and message(s) of a painting are revealed to me, or at least I understand them better when contemplating the finished work, it means that I have succeeded in doing something. If, sometimes, the results are different, or even in contrast to my initial intentions, it is even better.

Mystery – we are shrouded in mystery, life itself is a mystery, at least to me. I don’t happen to believe that God is an old man with a white beard, nor that a random lighting stroked into a pound and a “Swiss watch” resulted from that, by chance. Mystery is my emotional response to the above. I try to represent it in painting just as realistically (with the same clarity, intensity..) as I would paint a material object.

About altered-consciousness - If something in my painting evokes altered states of consciousness, it springs from my wonder and if it brings forth expanded consciousness instead, then it comes more from my understanding. I have more questions than answers. Apart from that, communication being a matter of both emission as well as reception, a glitch or poor signal on either side should not be excluded.

Have you ever collaborated on any pieces together?

Yes we did. Being both in the same studio, we would often exchange opinions. Sometimes he would ask me to paint on top of his work in order to demonstrate how I would fix or solve a particular painting of his that he was indecisive about or felt was going nowhere. I must’ve learned to sense what he was after, as many times he took my advice, sometimes even keeping my interventions into the final work as such, which ended up working unexpectedly well considering they were not meant to be definitive. I also did some work for him at his request, painting on some of his commissions, based on his sketches or other reference, at times when he was busy doing other paintings. He later asked me to work on his latest three mural paintings, in 2002 The Galaxy of Love, then in 2004-2005 Genesis and Enchantment. I am very grateful for being given the opportunity to paint on such a large scale, it was a very useful experience for me. My contribution made the execution a lot faster but in exchange for that, Sabin had to change his habitual process. If he would’ve worked alone, he would’ve normally made several small and unpolished projects that he would have taken the liberty to disregard in the final work, reliving the whole thing fresh. This would’ve impregnated every brushstroke with his life’s vigor and, sometimes, convoluted paths leading to unanticipated revelations. Now he constricted himself to consume all this activity on the reduced scale as he had to produce the detailed projects needed as reference for me to paint from. The careful projects benefited the works with more precise drawing and carefully considered compositions but to the same extent left less room for Sabin to surprise himself on the final execution.

Words: Alexia Marmara and Tudor BălașaImages courtesy of Tudor Bălașahttps://www.tudorbalasa.comhttps://www.sabinbalasa.com