Mending a Better Ending

Rachelle Francis and Diana Francis

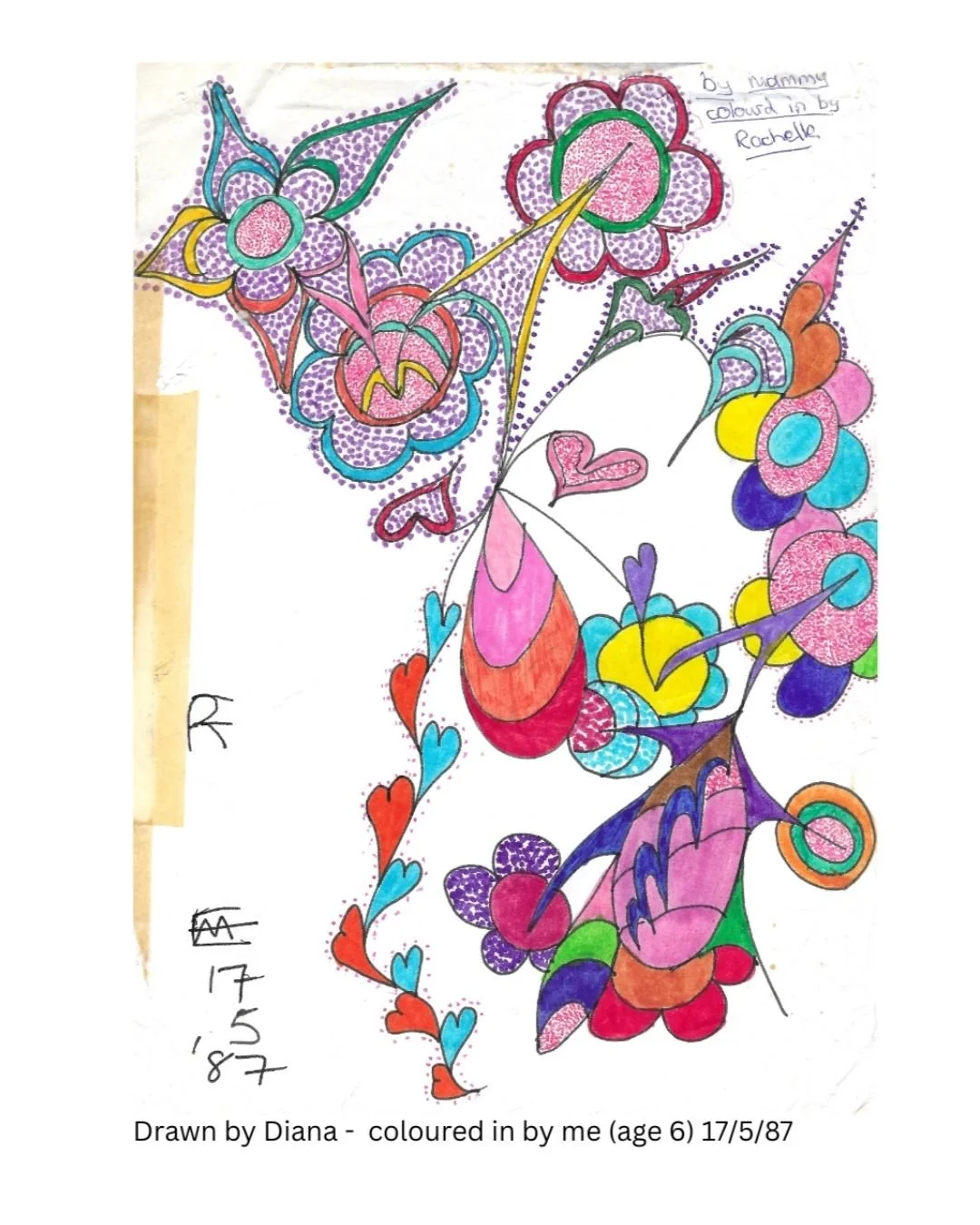

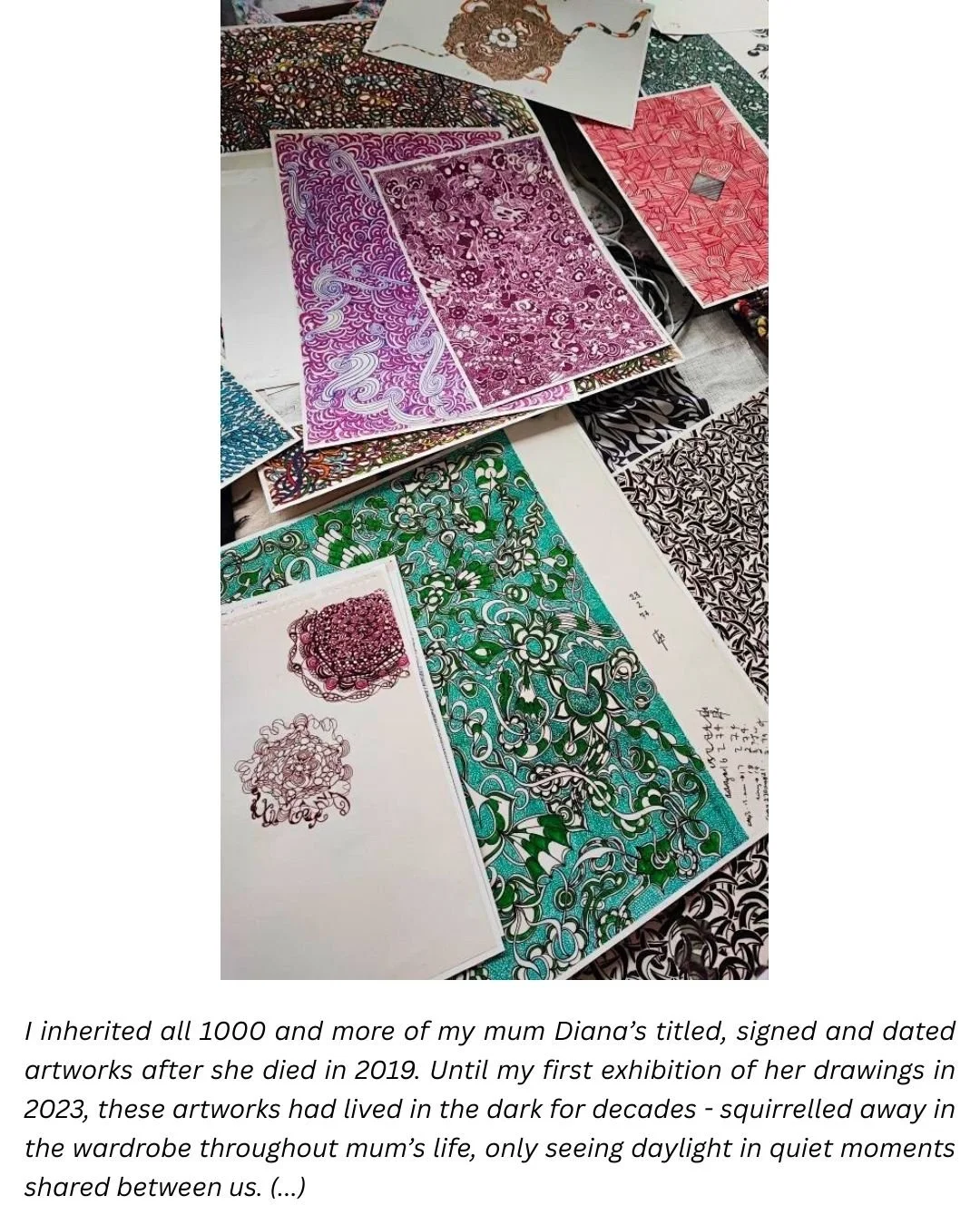

I inherited all 1000 and more of my mum Diana’s titled, signed and dated artworks after she died in 2019. Until my first exhibition of her drawings in 2023, these artworks had lived in the dark for decades - squirrelled away in the wardrobe throughout mum’s life, only seeing daylight in quiet moments shared between us.

Diana grew up living and working in her family's hotel. She was dealt a sharp hand in life, and her sensitive skin experienced the blade deeply. Some of the significant markers in her life read like a shopping list of things you would never want to buy: an abusive elder brother; a dad I knew she loved deeply (but who I have discovered might also been abusive); a mother who told her she was ugly (paying for a nose job in an attempt to ‘fix her’), mental illness and suicide attempts; a parental affair and divorce; an alcoholic dad who fell down the stairs and died on her wedding anniversary; a stillbirth and a failed pub business in the same year as her dad’s death; an estranged relationship with her twin; a hysterectomy, a husband’s affair followed by a divorce; a diagnosis of chronic anxiety and depression; doctors suggestions of autism and / or a personality disorder (we’ll never know) - and an alcohol addiction, cirrhiosis and COPD, a terminal lung disease caused by her addiction. I think the birth of myself and my two siblings interrupted this dark shopping list like three warm glows - mum told us that giving birth were the happiest moments of her life.

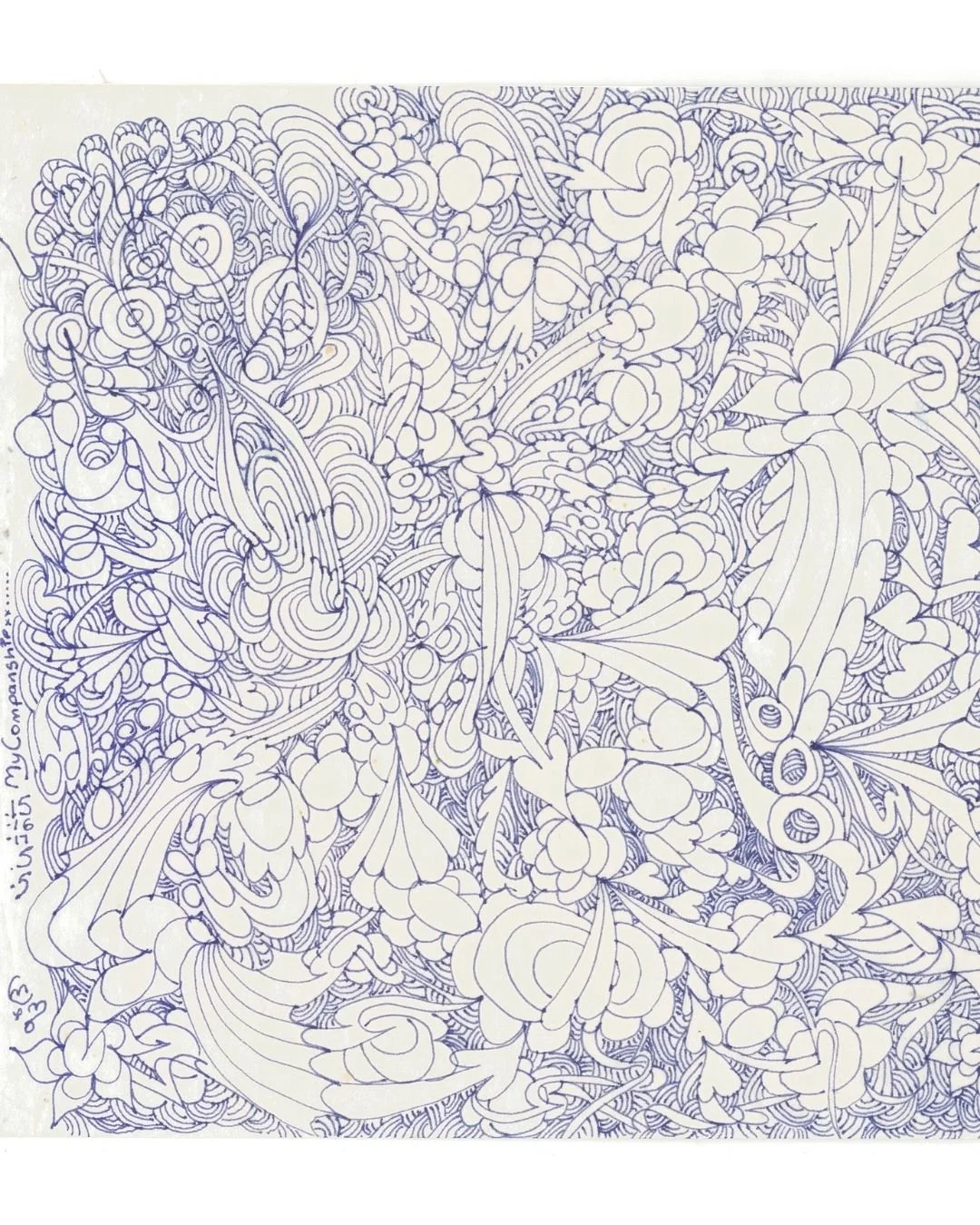

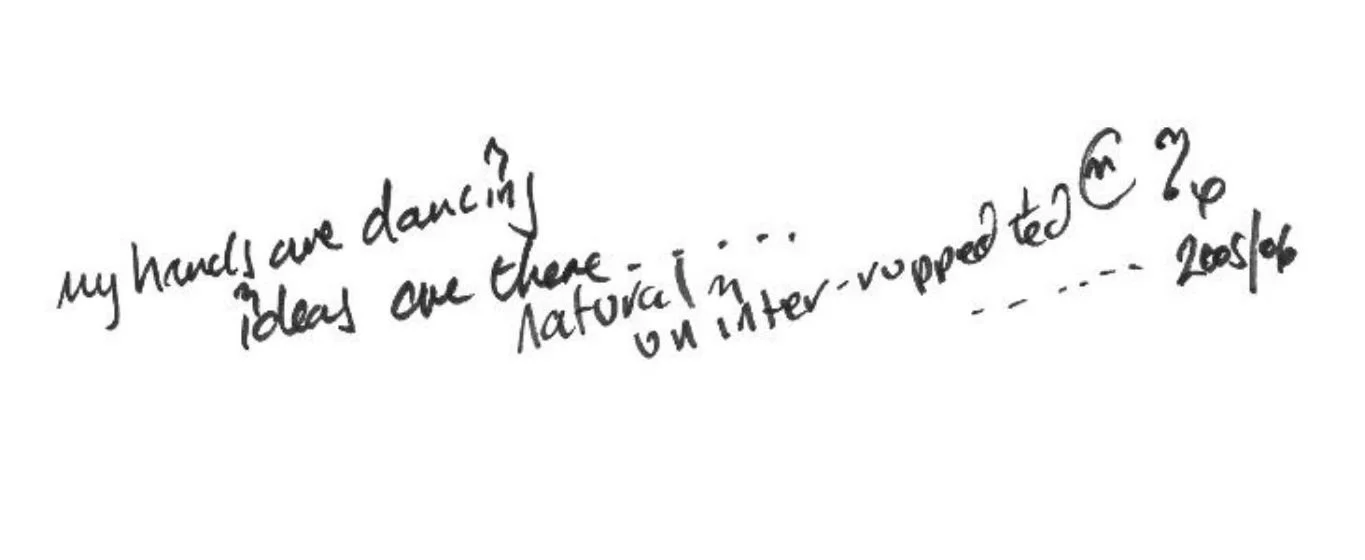

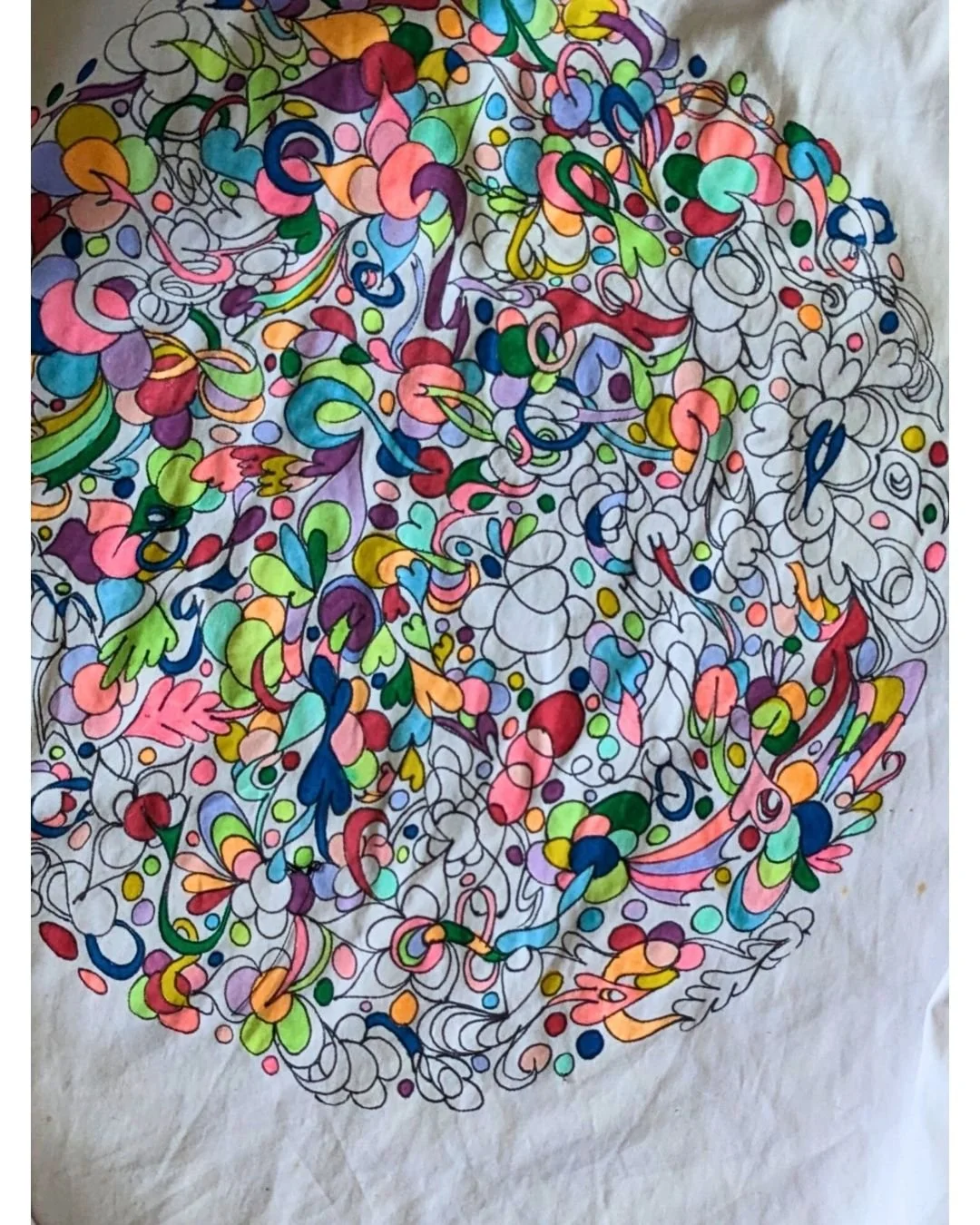

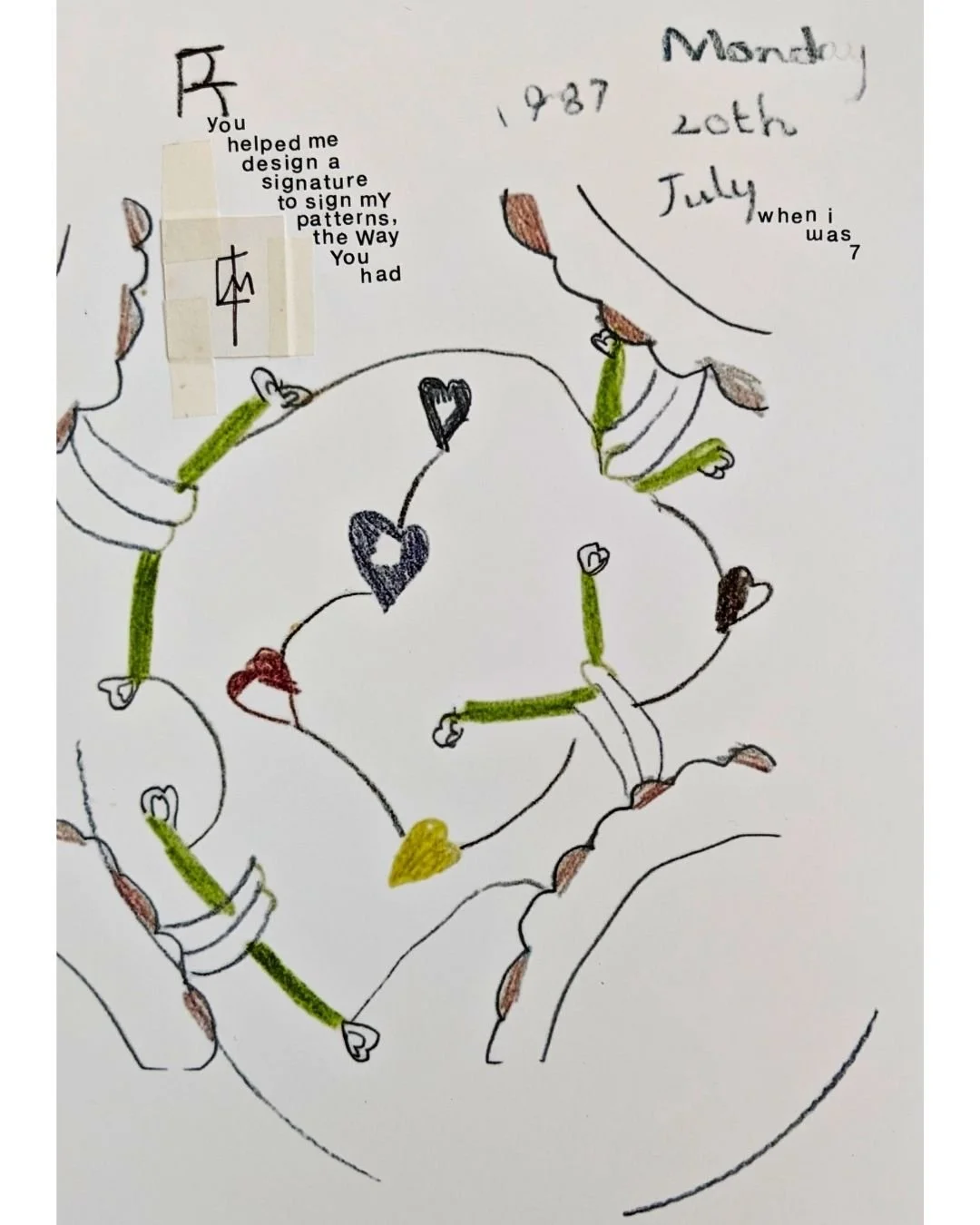

The artworks she made in this life of hers, I think they too were a series of warm glows that helped her see in the dark. For 50 years, compulsive pattern doodling - private calming acts of self expression - provided sanctuary, escape and company. Felt tip and paper were her friends; her home and her passion. Mum's drawings lit my world too - although always stored in that wardrobe, her artworks burned bright in my subconscious and guided me towards my career in textile design. A deep rooted love of pattern-making connected me to mum. My hands naturally spoke her visual language - her shapes, my shapes.

I grew up aware that the value of mum’s drawings ran deeper than their paper surface. When dad divorced her I found myself on some kind of long distance unofficial suicide watch. Knowing that her gift of drawing had been her past lifeline I was more than absolutely grateful to encourage her to reunite with her old felt tip friends. So, after a 20 year hiatus she started drawing again and we emailed almost daily. She would draw and I would cheerlead. If she was drawing, I knew she was alive. She eventually went on to obtain a degree in Fine Art aged 60 at the local college.

Making art bought mum numerous benefits - but she needed real friends in human form and professional mental health care to help unpack that shopping bag of traumatic ingredients. And so tragically, during these mature student years she also began self medicating with alcohol.

And so began what appeared to my eyes a kind of long slow suicide. Witnessing the gradual landslide of her body and mind, I felt scared for her - and eventually, scared OF her.

Just before she became bed bound she handed me her final 300 artworks, nestled in an old envelope I had once posted to her. I hid them in a drawer because I couldn’t bear to look at these patterns made by someone I no longer recognised, who had hurt me and pushed me away whilst gripped by addiction. Now it was too late and the words were stuck in my throat and I didn’t want her drawing’s, I wanted her.

Her last artwork was left unfinished just three months before she died. A blanket of tiny half drawn stars in blue biro on the back of a ripped up bill. The only thing that was crystal in the dark sky of this period were her repeated words “I’m worried about my arts and crafts, look after my arts and crafts.”

She died to a backdrop of fireworks on NYE in 2019.

All the artworks left her house and arrived in mine.

Unable to look after mum in her addiction bound period, to look after her arts and crafts in her deathtime period is a cathartic relief. Now she WAS the artwork and now I could care for her.

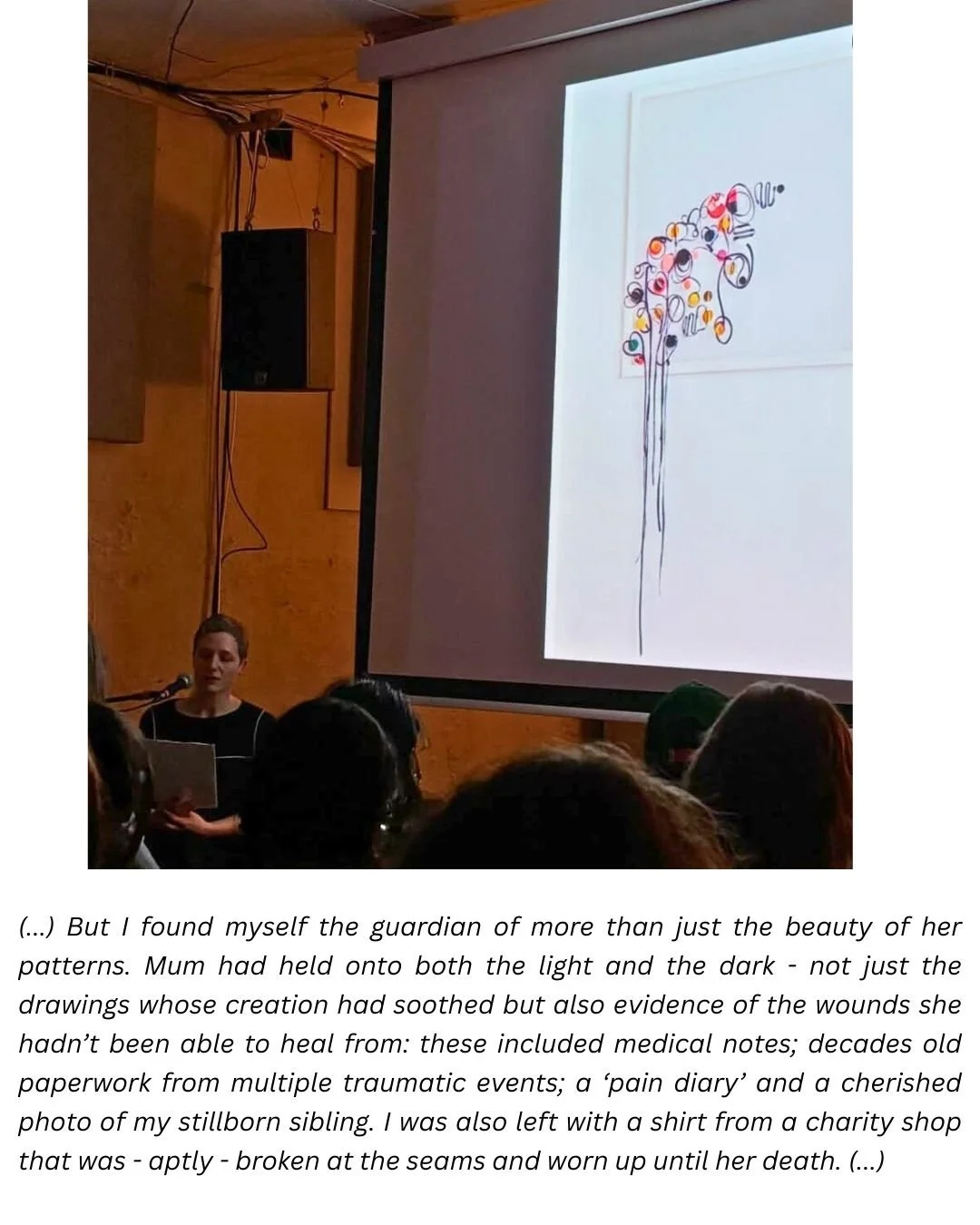

But I found myself the guardian of more than just the beauty of her patterns. Mum had held onto both the light and the dark - not just the drawings whose creation had soothed but also evidence of the wounds she hadn’t been able to heal from: these included medical notes, a ‘pain diary’, divorce paperwork and a cherished photo of my stillborn sibling. I was also left with a shirt from a charity shop that was - aptly - broken at the seams and worn up until her death.

Her wounds, now in my living room. My heart, now broken.

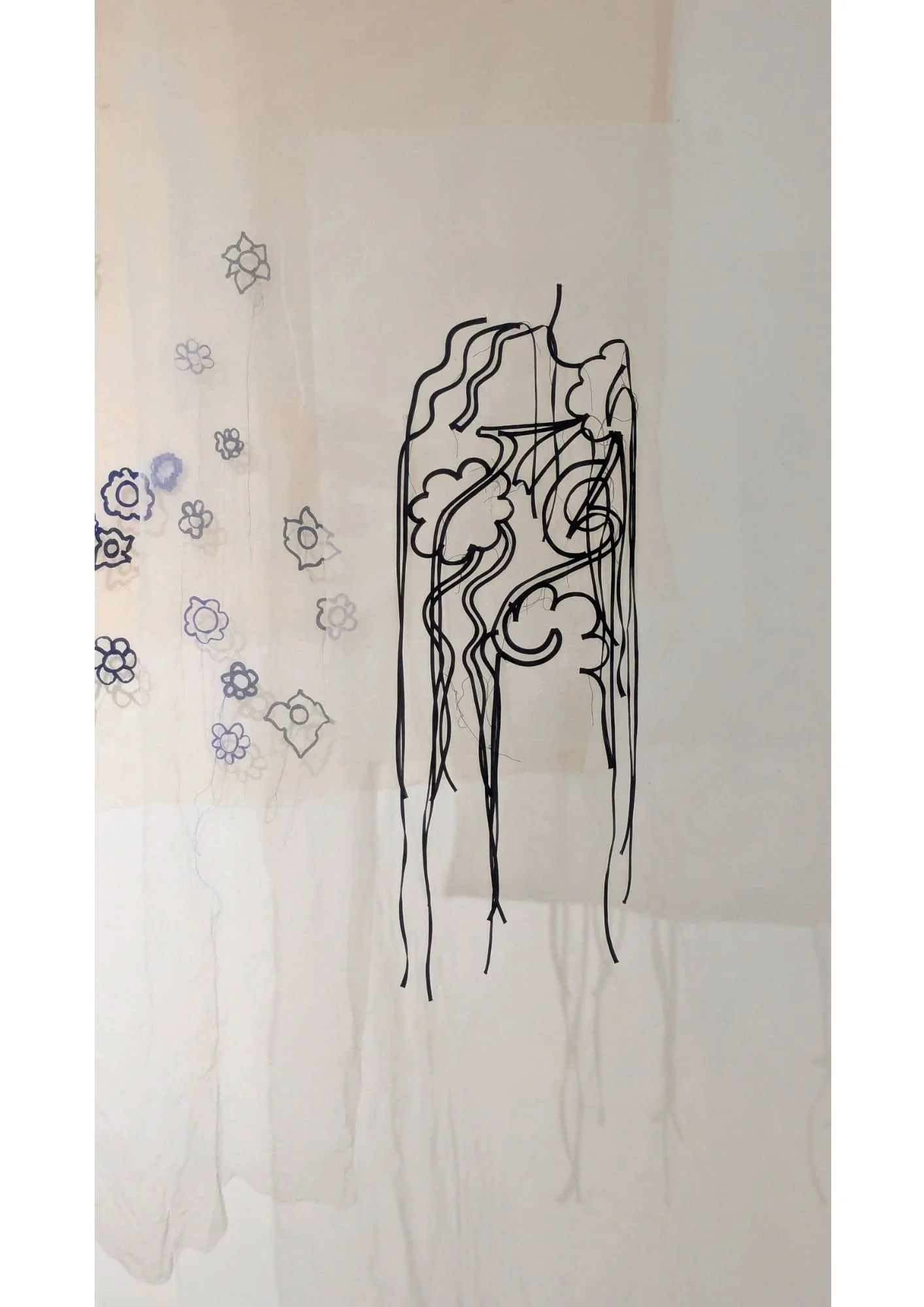

Confronted with this painful body of pieces of mum, I found myself naturally turning to sewing for self expression and self medication, comforted in the company of needle and thread in the way mum had been comforted in the company of felt tips and paper.

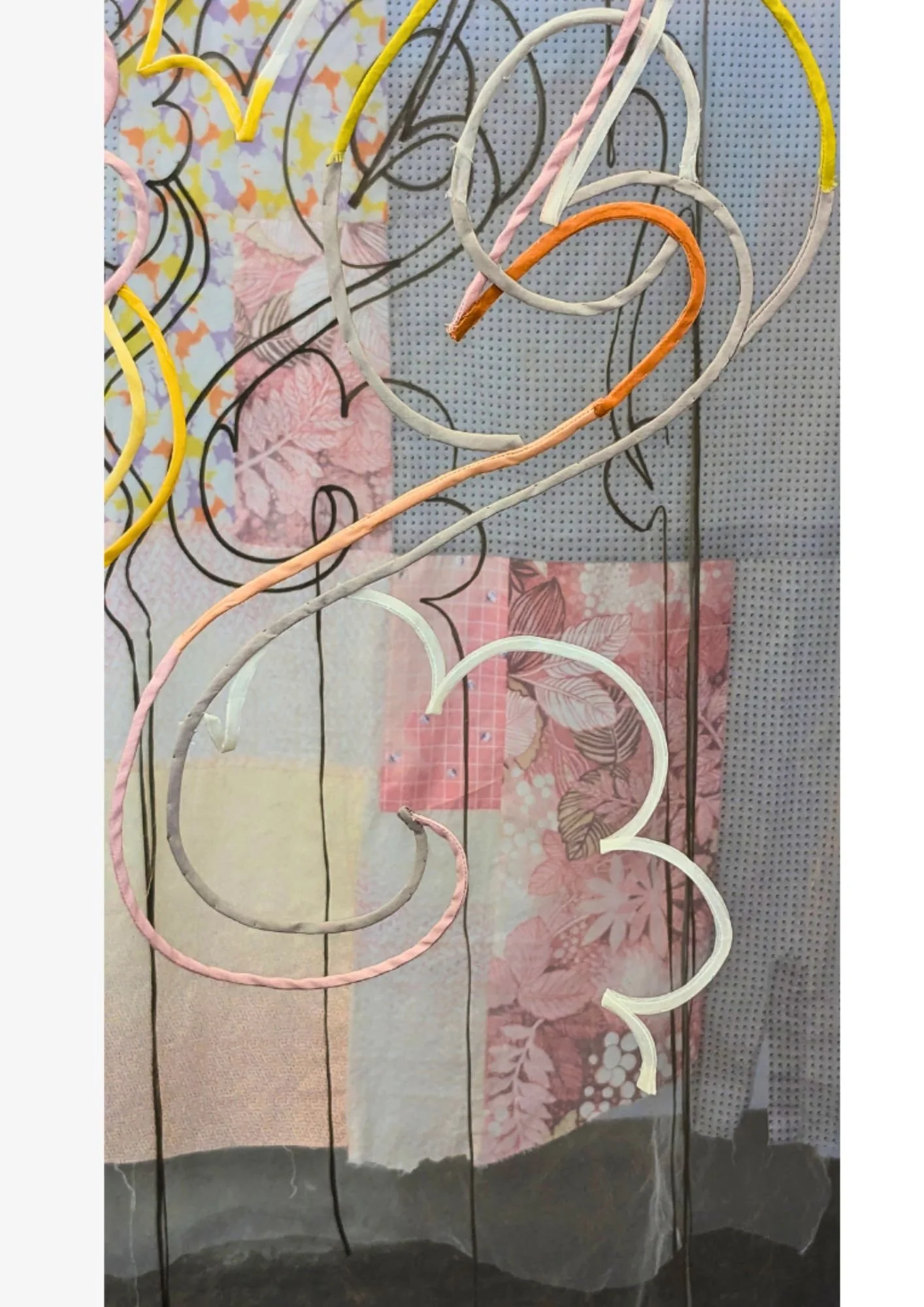

It's no surprise I turned to the creative thread that tied us. Sewing was always my shortcut to feeling close to mum. She was the definition of patient, teaching me to knit, stitch, thread and unpick from as early as I can remember. So obviously 8 weeks after she died I turned to sewing when looking to find her. With my breath out that followed her full stop I now had the lungpower to begin the work that had sat in my peripheral vision for years: a creative collaboration. Because she WAS the artwork, my needle now had the ability to set her pattern and her Self into movement and flight, to help free her from the living room and the mind she had become trapped. Blowing up minuscule areas of her intricate drawings into 3d embellishments I was now able to tempt her out of the tight spaces in which she had lost herself and announce ‘she WAS here, and look how beautiful she IS’.

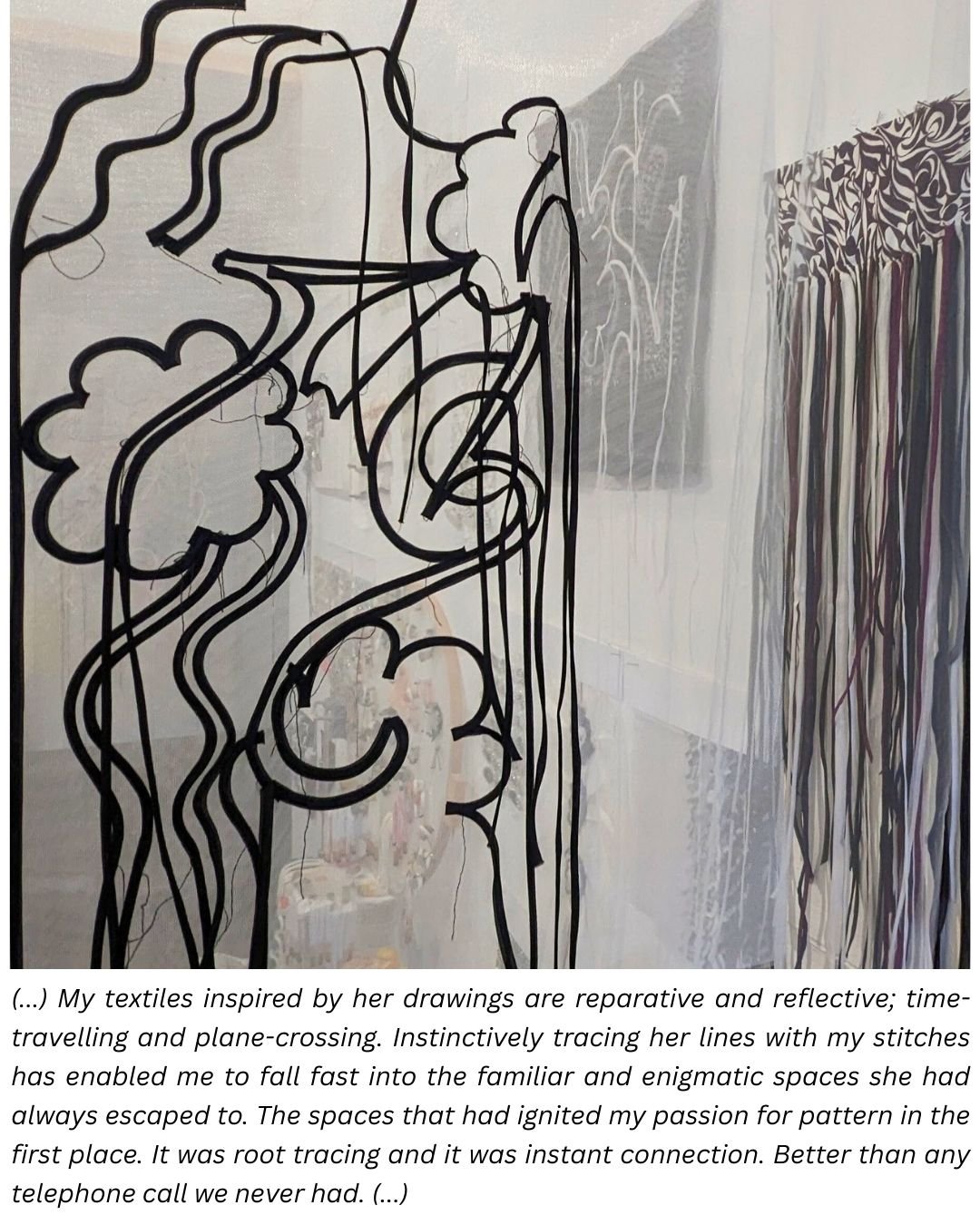

My textiles inspired by her drawings are reparative and reflective; time-travelling and plane-crossing. Instinctively tracing her lines with my stitches has enabled me to fall fast into the familiar and enigmatic spaces she had always escaped to. The spaces that had ignited my passion for pattern in the first place. It was root tracing and it was instant connection. Better than any telephone call we never had.

Working with the shapes and swirls of her inked soul I have spoken to her more than I ever could in her lifetime. Leaning into the light and dark of her archive, I can now break the silence and start the hard conversations. Beneath the waters of her paper pond lie all the versions of her: abused child; suicidal teen; romantic twenty something; doting mum; grieving mum; anxious mum; depressed mum; isolated mum; addicted mum; absent mum; terminally ill mum; dead mum. Slow stitch-work gifts me a soft space for these meetings; these dives into the past. I can safely move with my needle to shift heavy secrets and shame, exposing all the messy ends to repair and craft my own narrative. It's like turning a light on in a dark room. Through my stitches born from her patterns I can really see the Diana I want to be reminded of and spend time with the mother I wish I'd never lost.

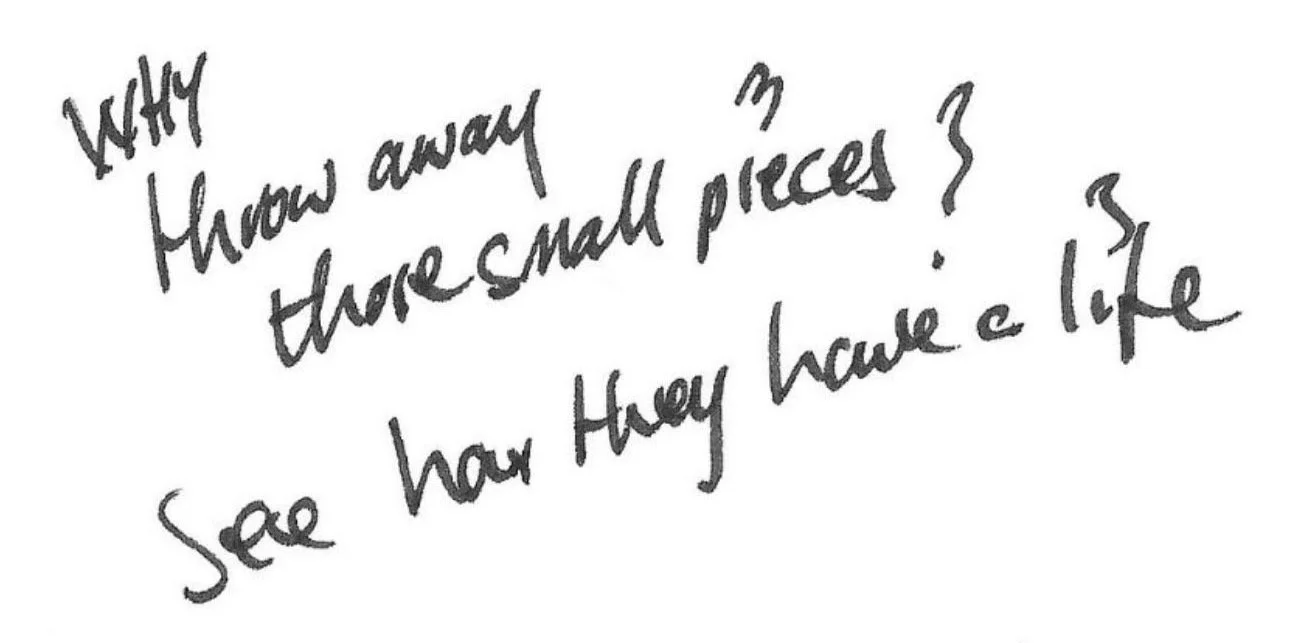

With this work I feel I am mending a better ending to our story: an afterlife in fabric form - and I really think mum is ok with this. Handwritten notes found amongst her artworks give me the thumbs up. One of which seems loud in agreement - it reads: ‘Why throw away those small pieces? See how they have a life' …

words: Rachelle Francisall images courtesy of Rachelle FrancisThis beautiful text was shared at the Amurmur launch event at The Horse Hospital 18/12