Did I find you, Jean de Bosschère, through your undaily cosmos?

In love with the brush of a ghost again!

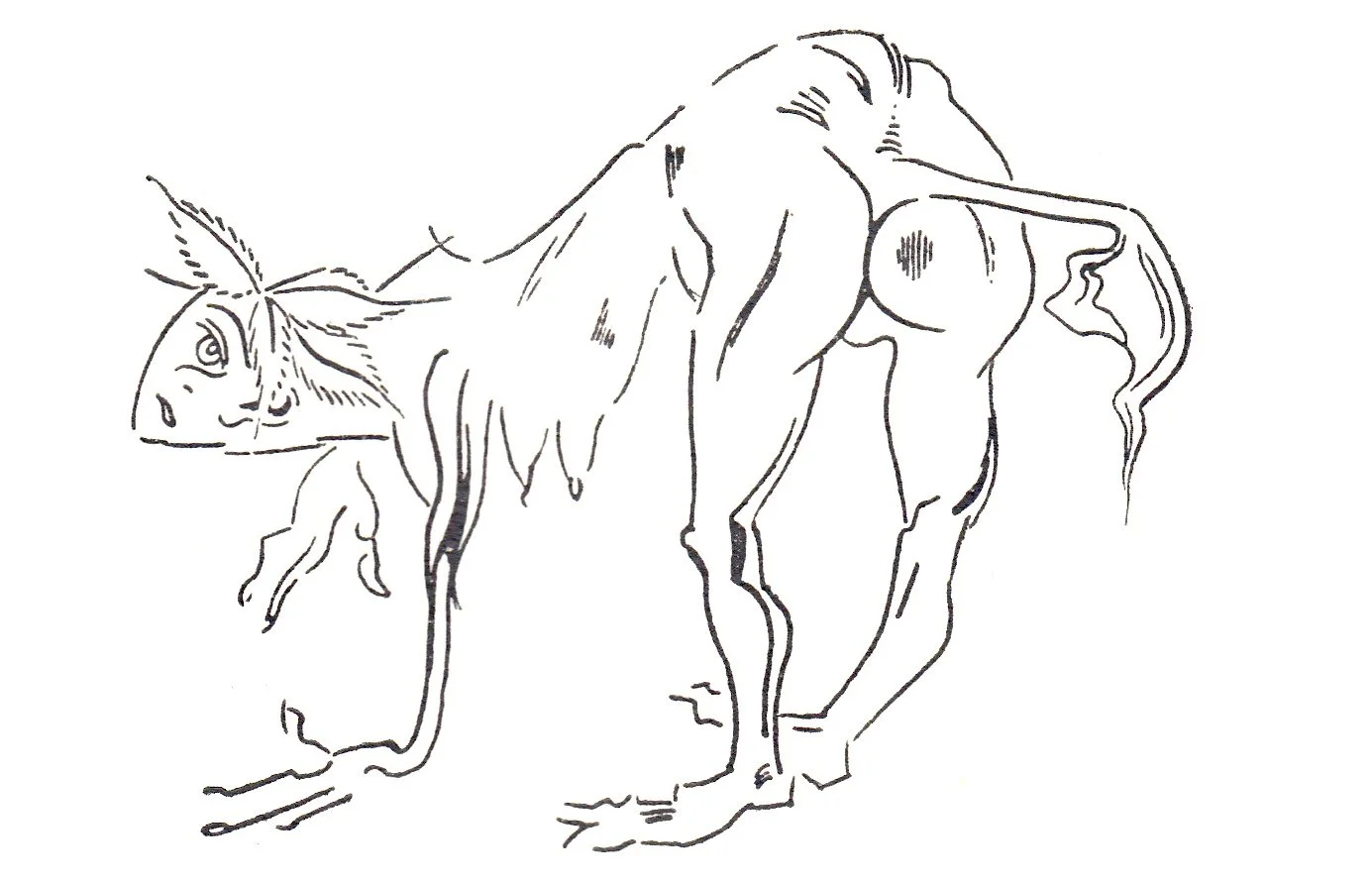

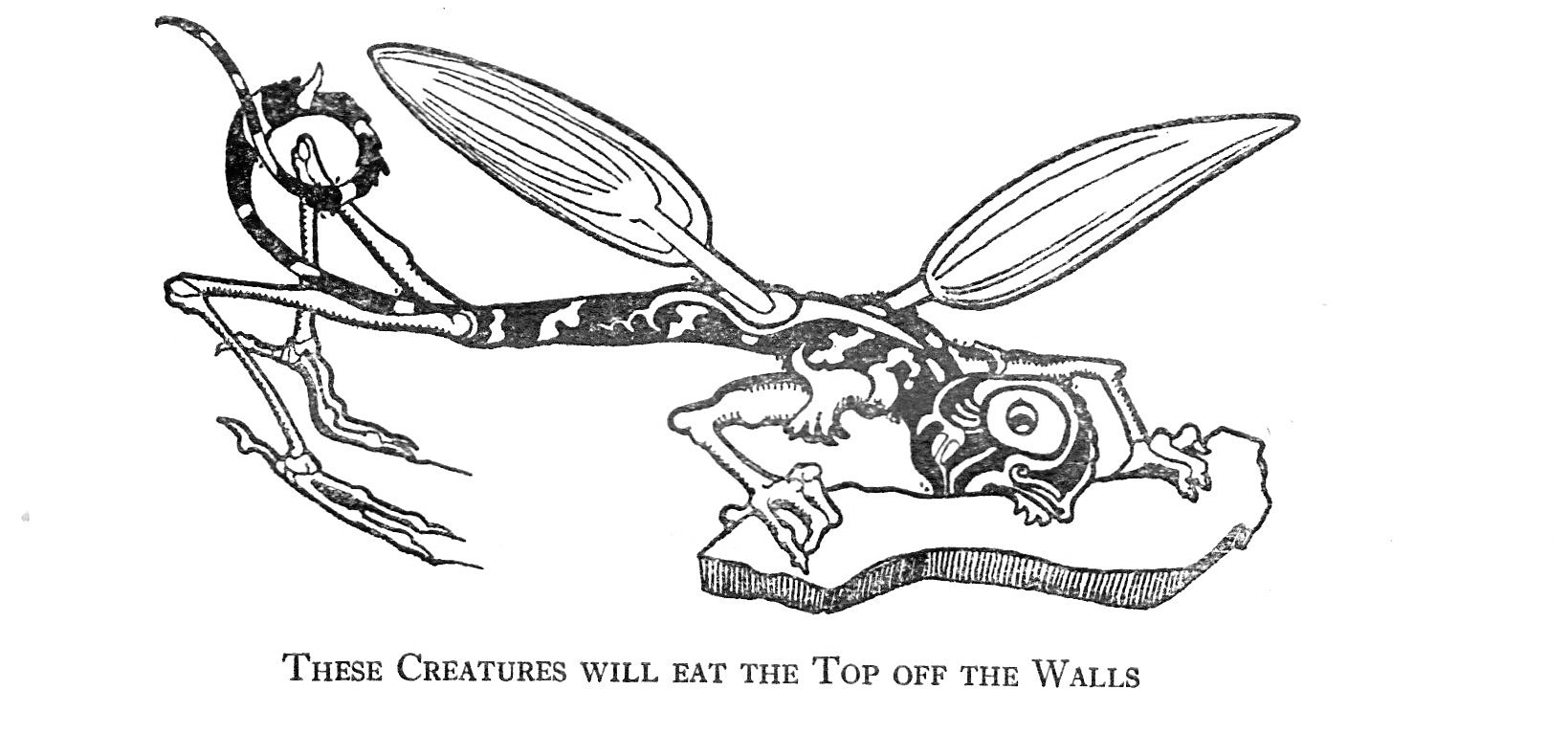

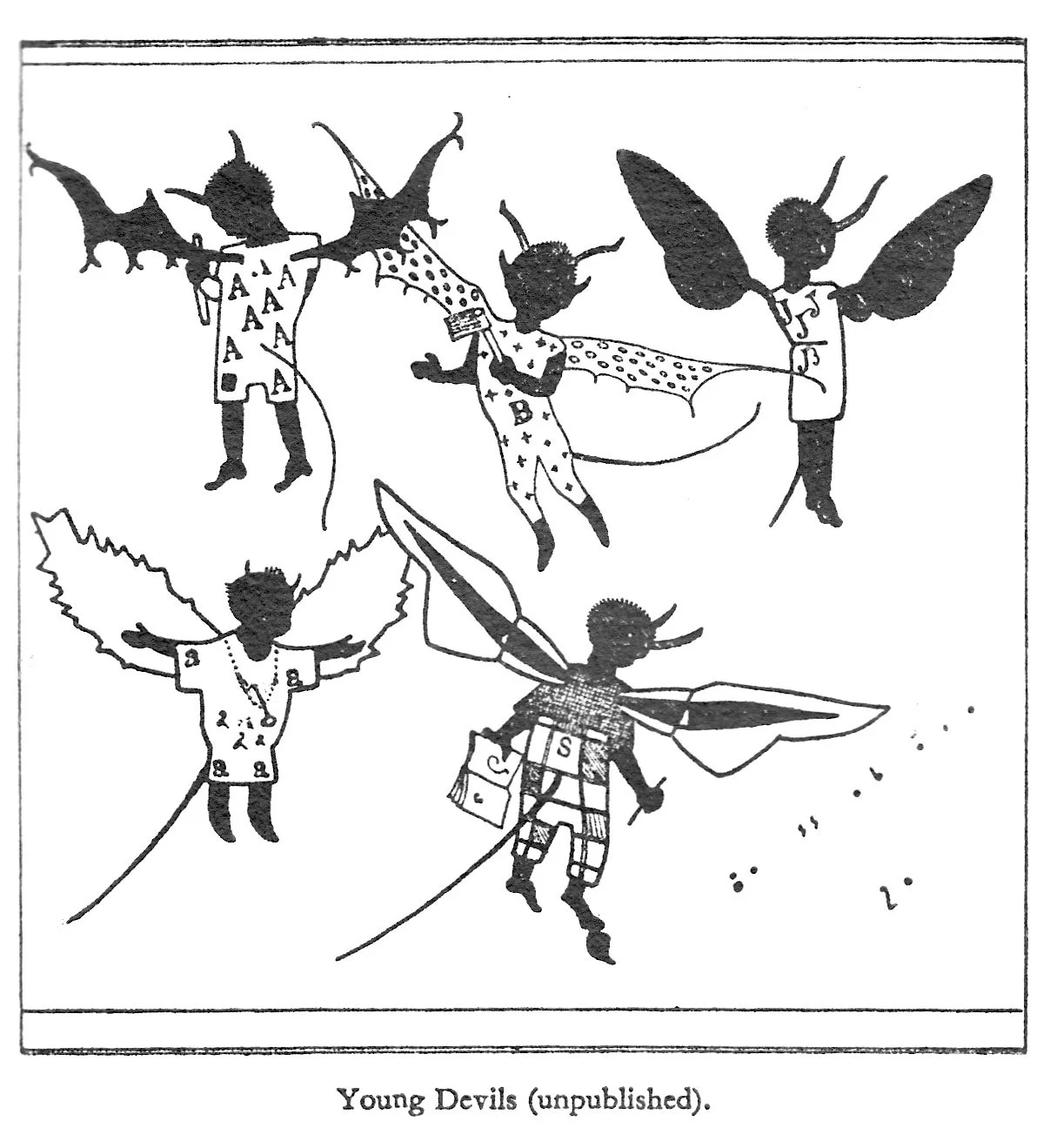

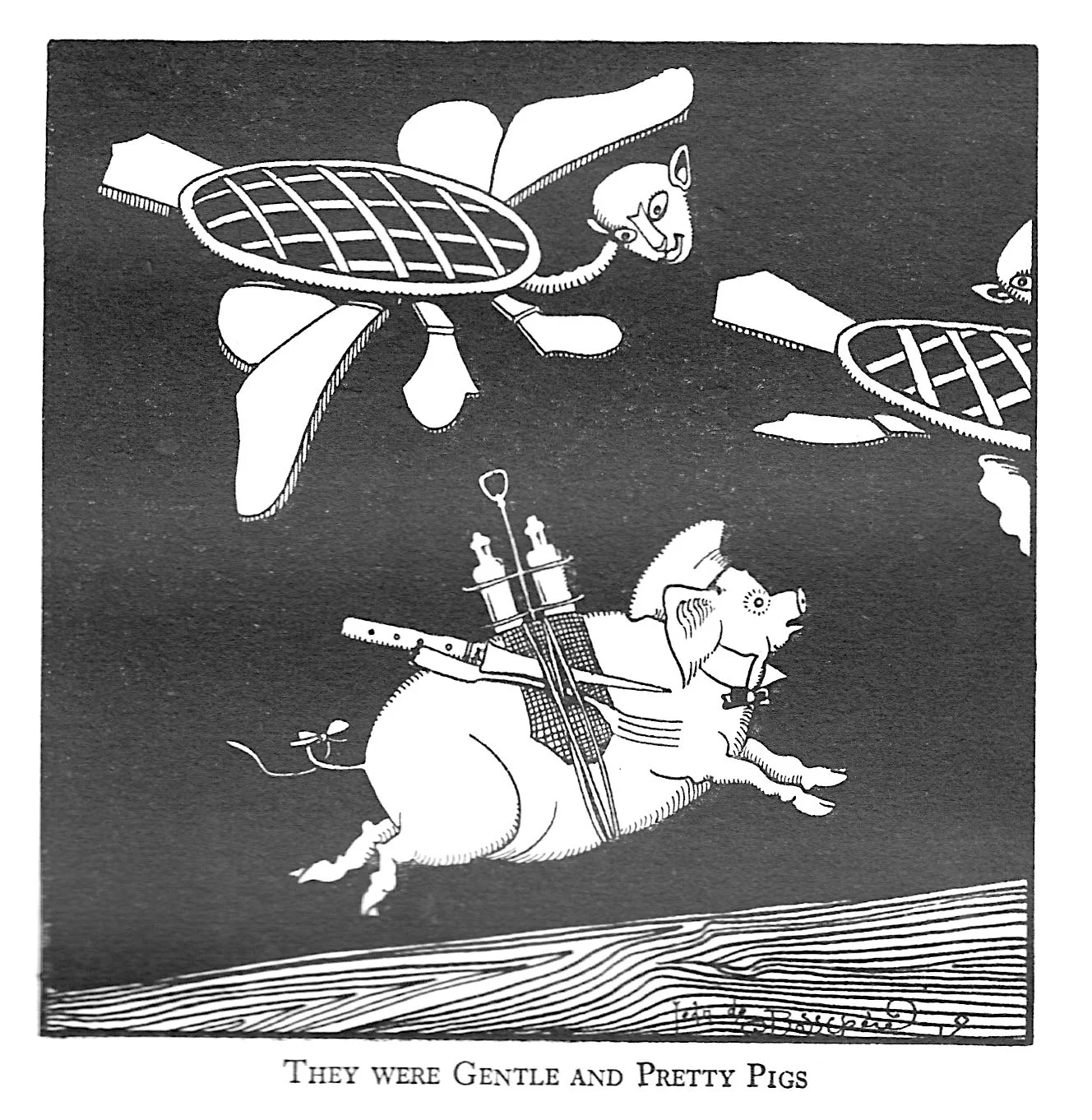

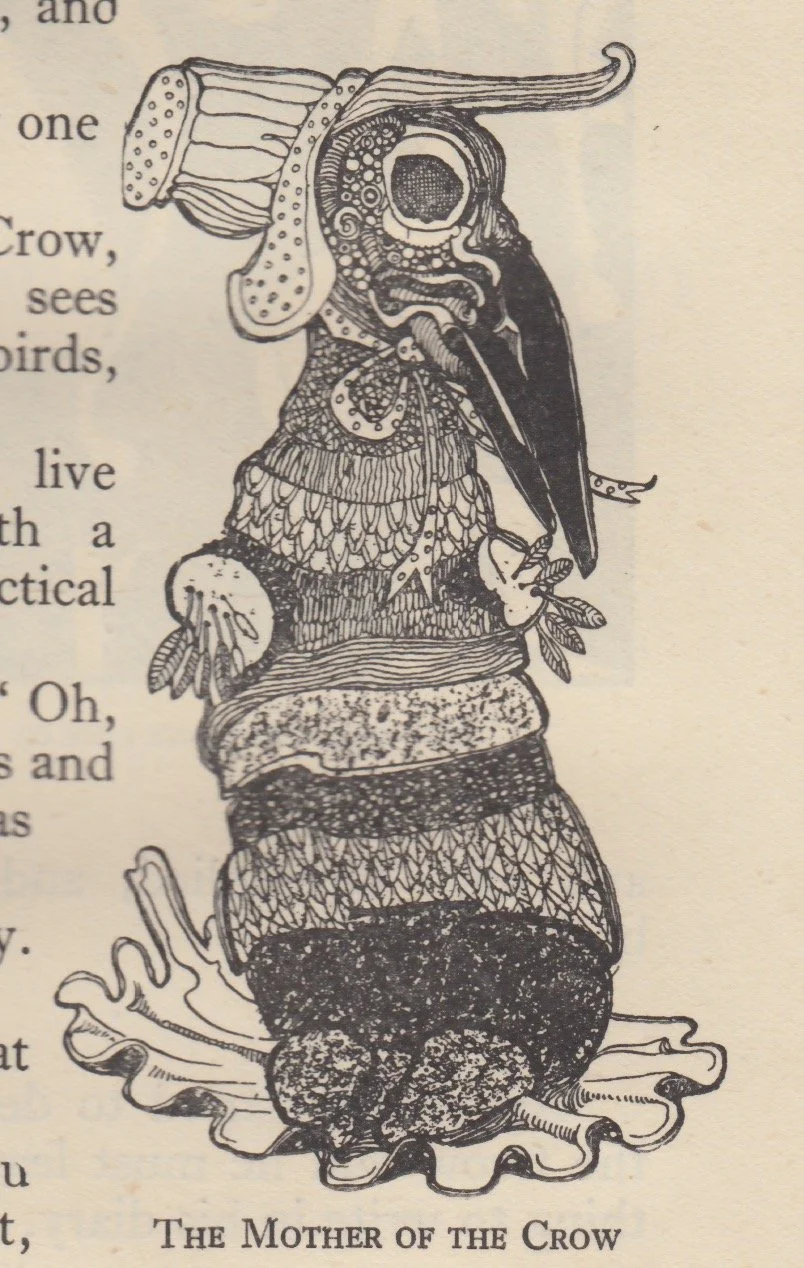

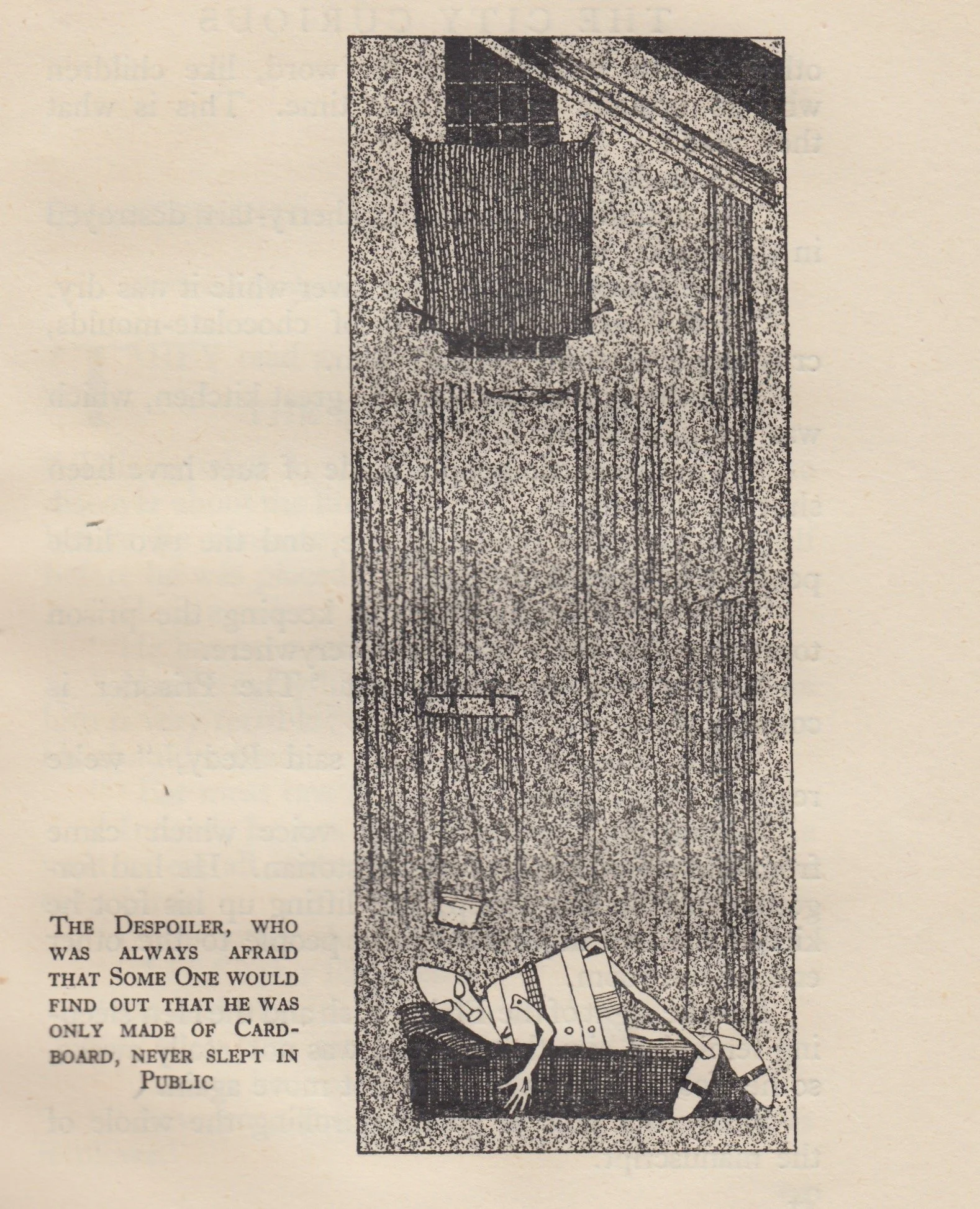

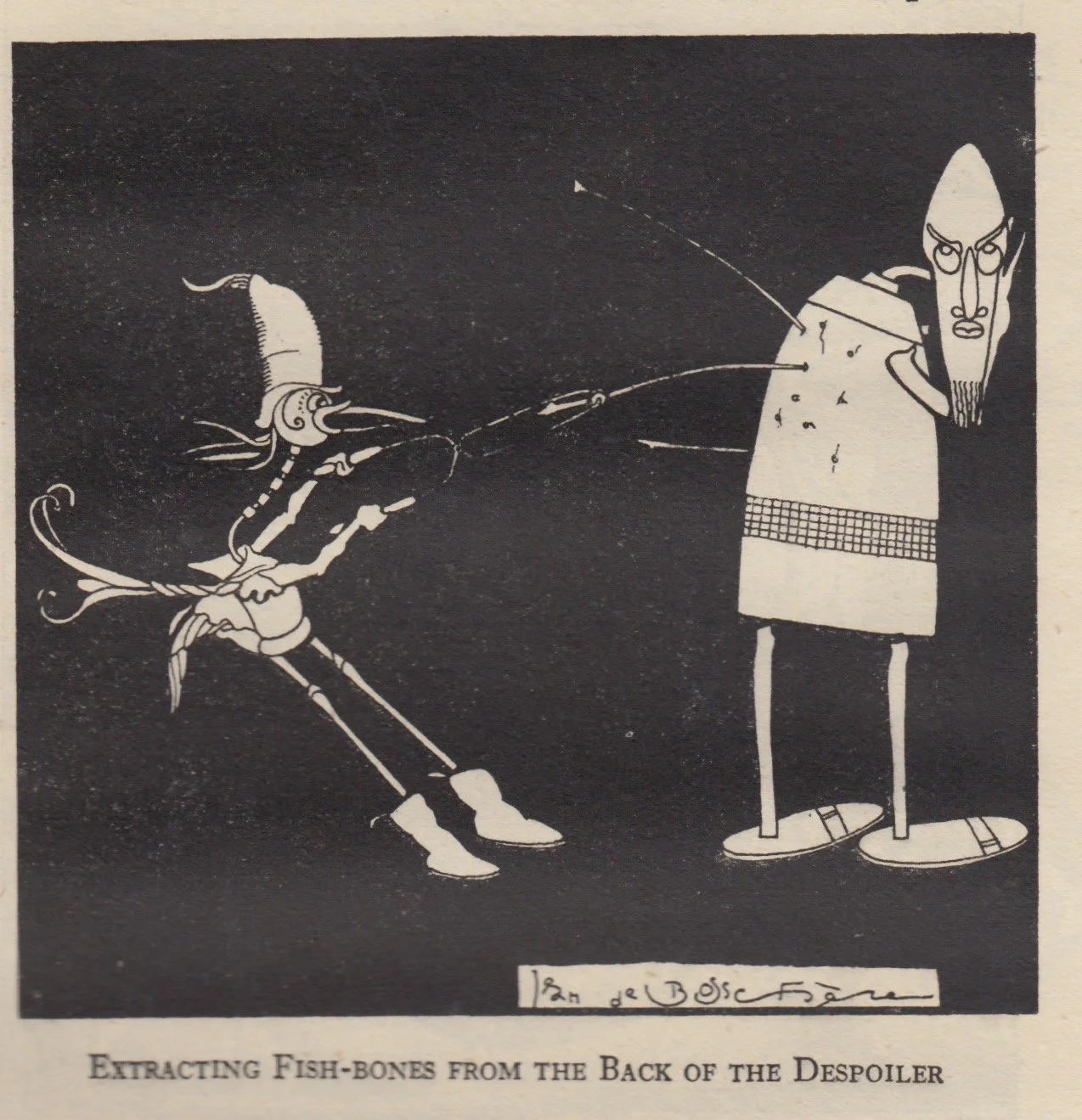

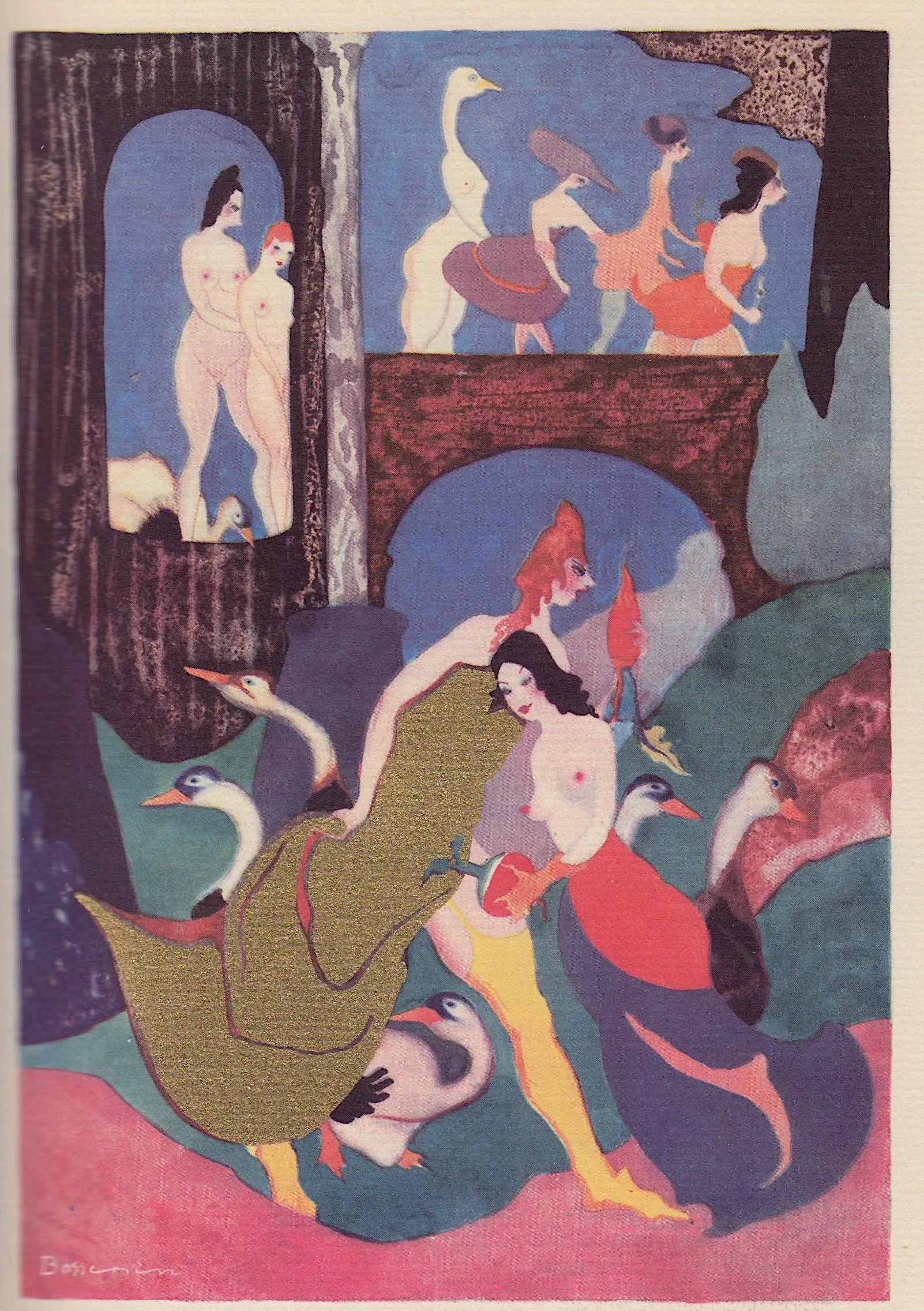

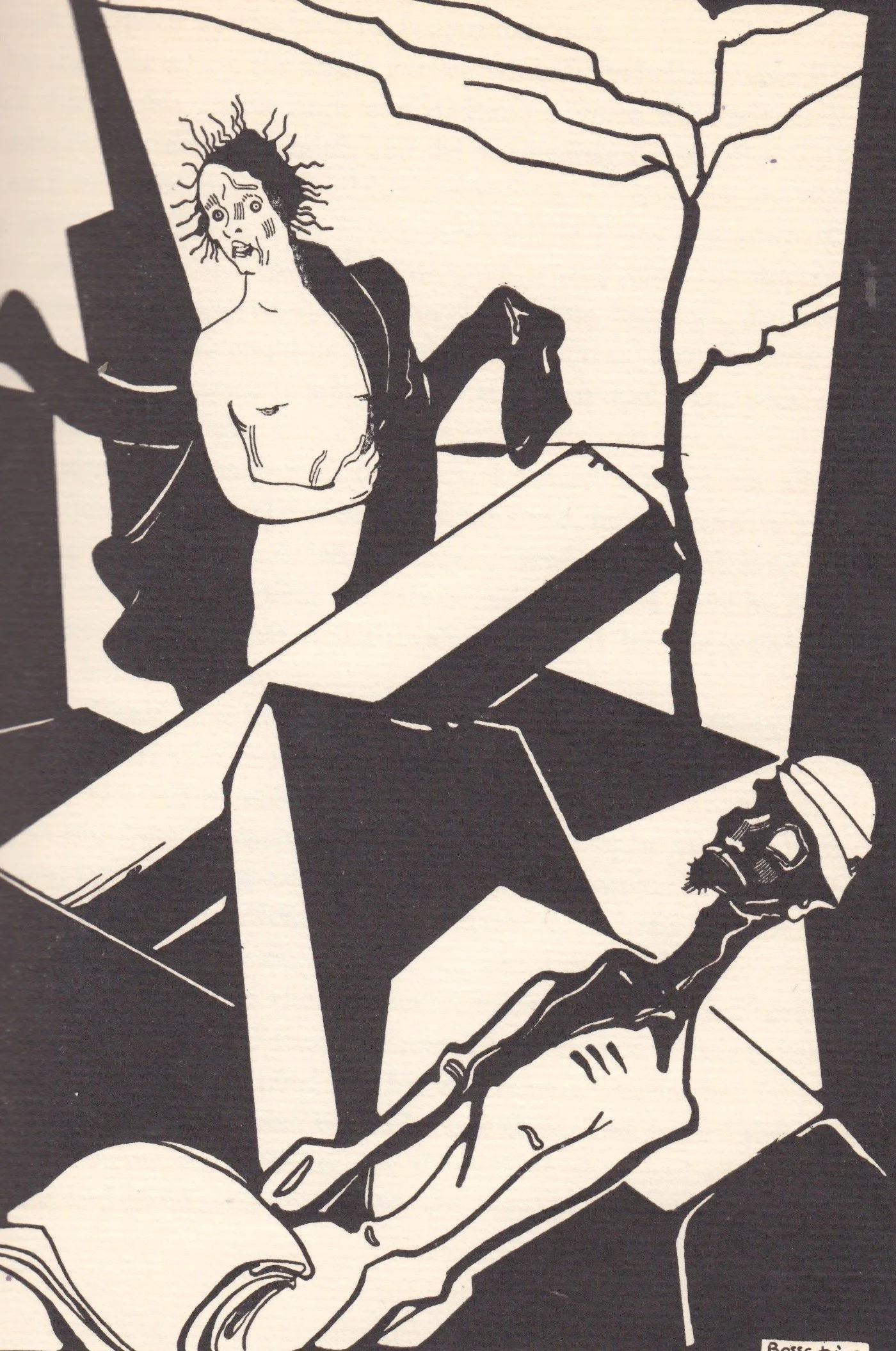

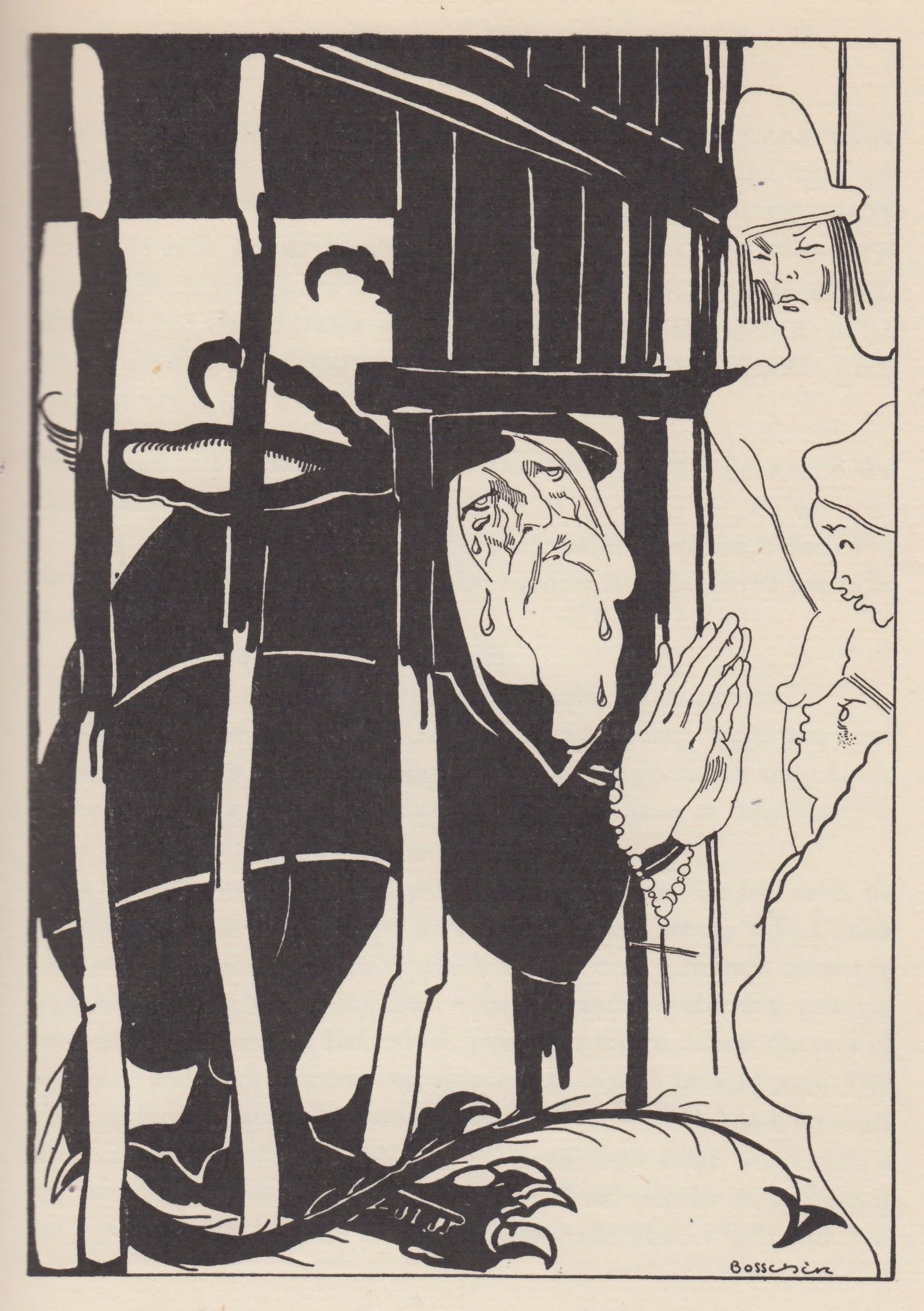

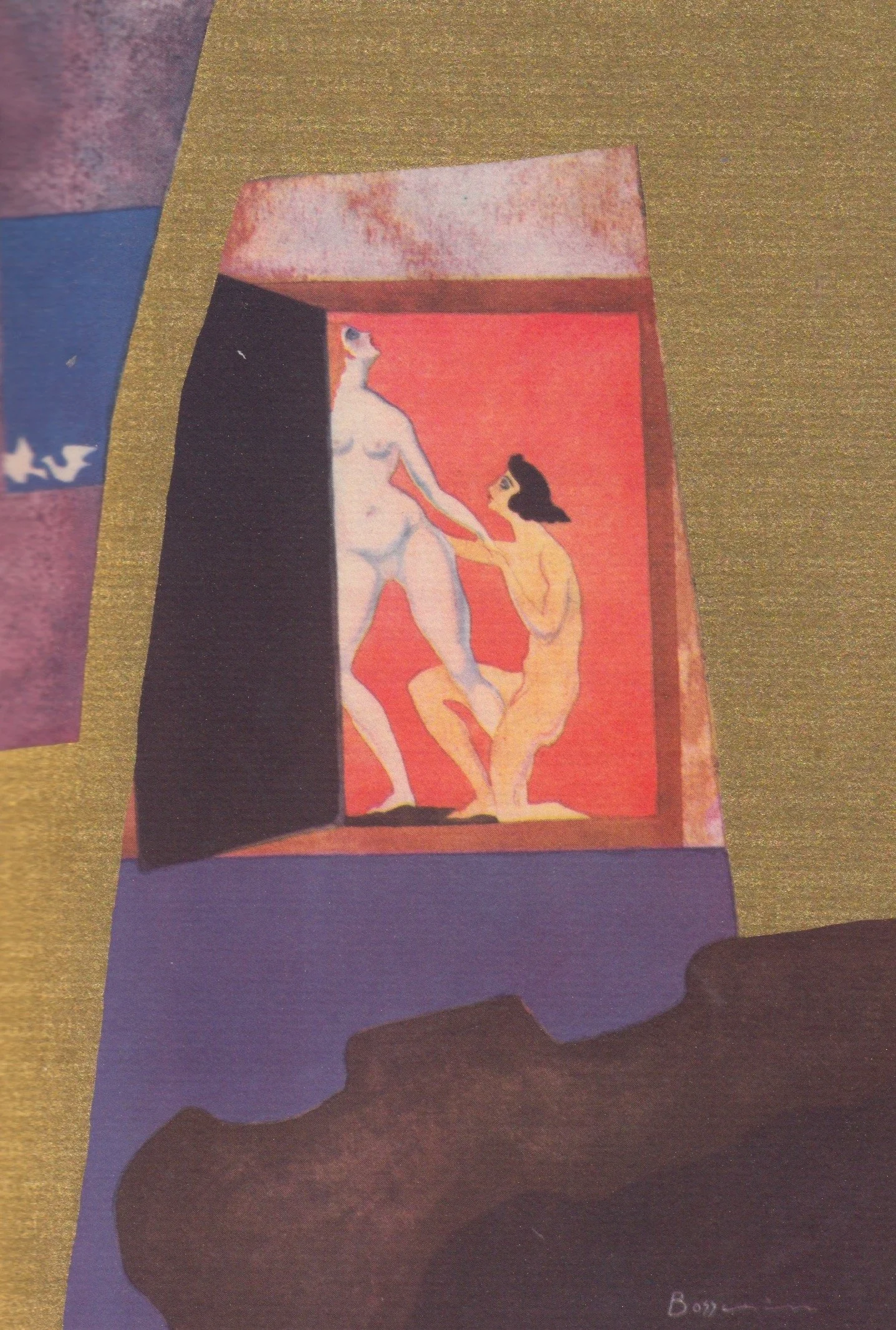

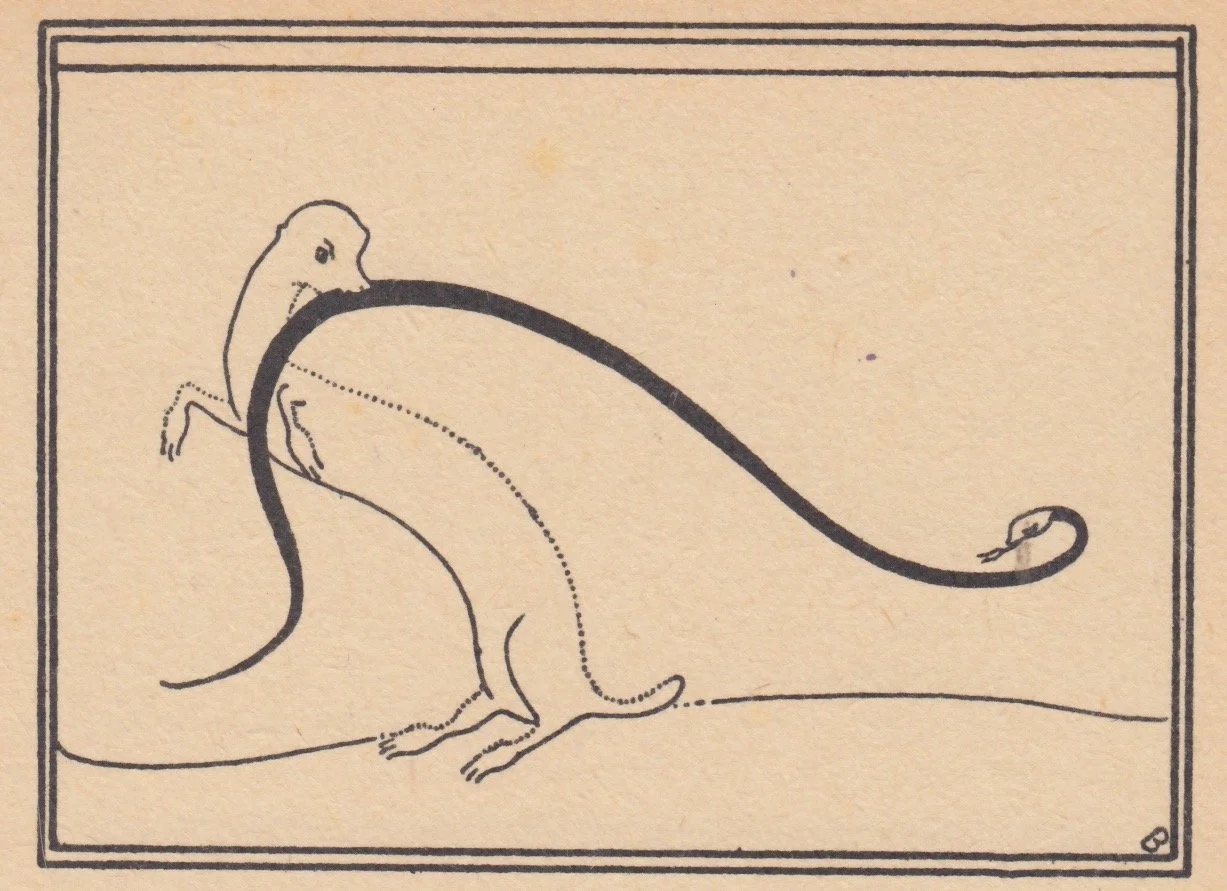

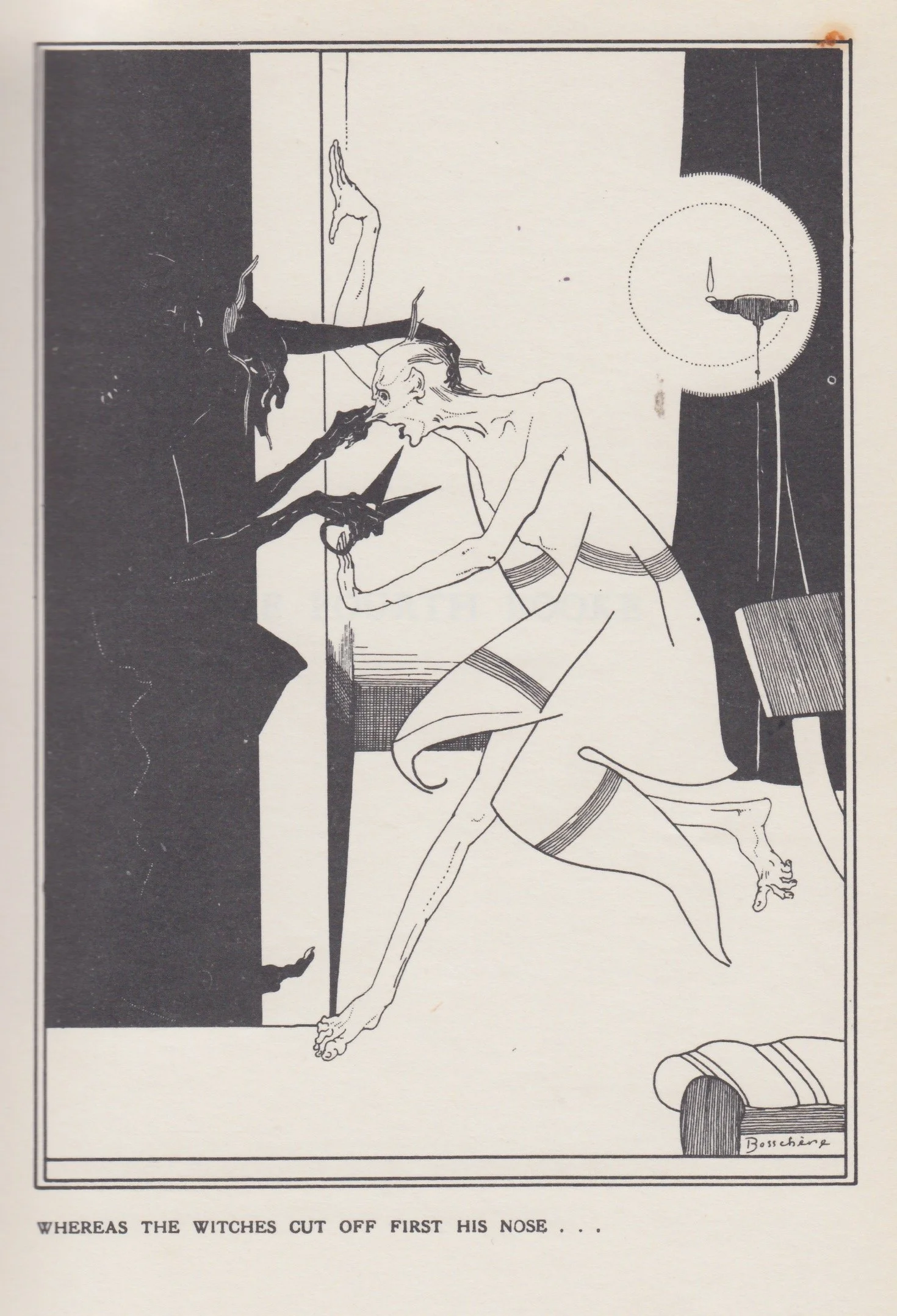

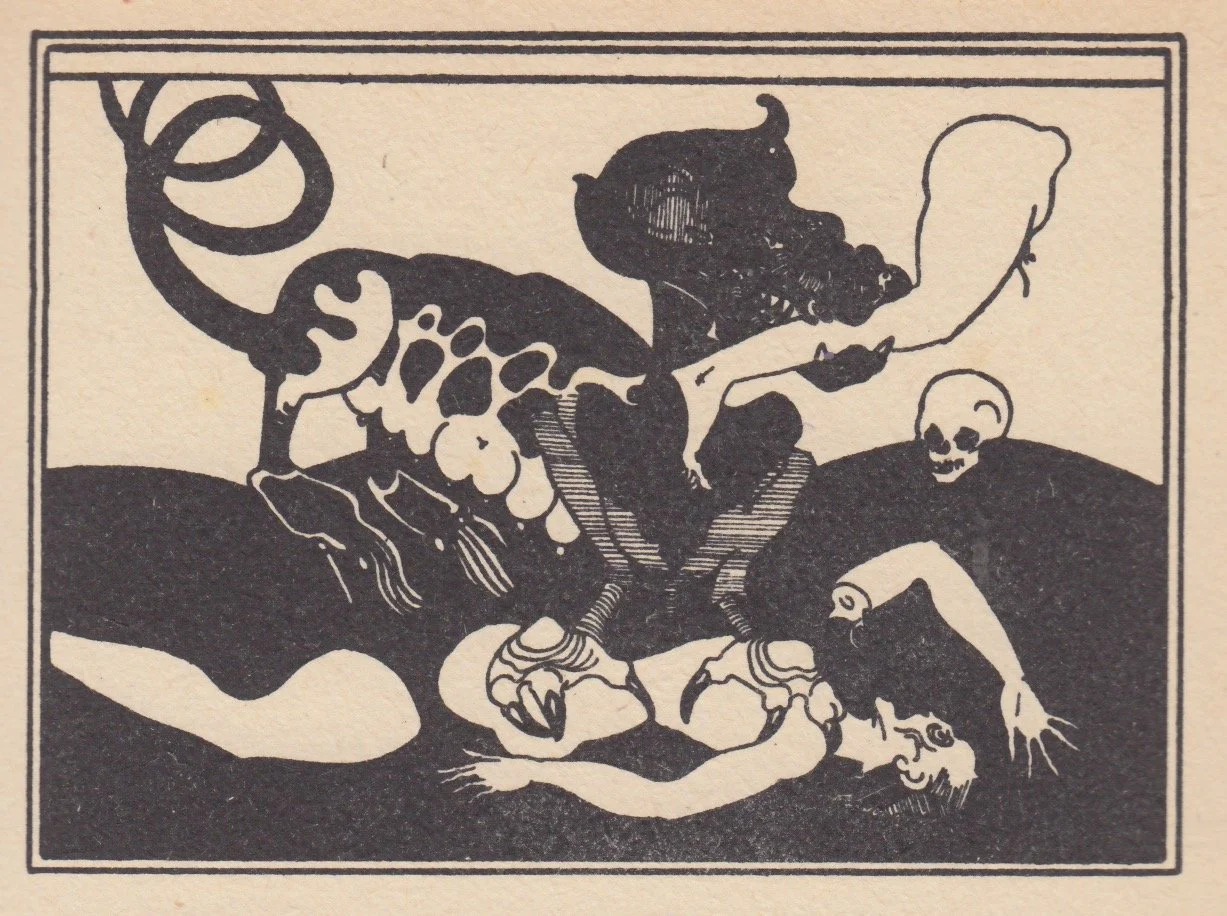

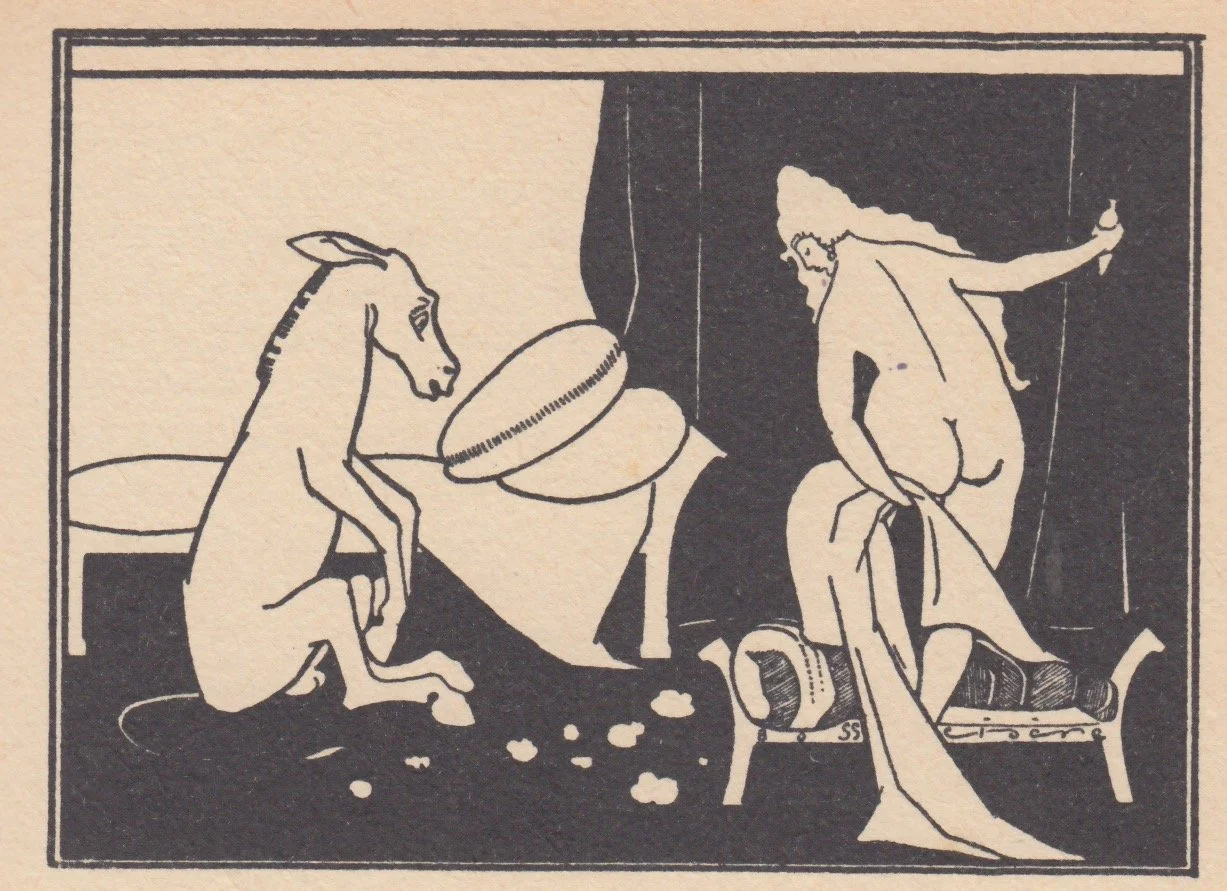

the images accompanying the following text are from "The World of Jean de Bosschère" by Samuel Putnam (The Fortune Press, 1932) / "The City Curious" by Jean de Bosschère, translated by F. Tennyson Jesse (William Heinemann, 1920)For the last few years I’ve been in an impassioned relationship with a ghost. He belongs somewhere far away from me, all the way in Mexico where the memory of him is kept by very few people. These are his last standing archivists. I speak to him regularly, will see him never. I glance at the thought of him through his works, through his paintings. I’m tirelessly working to release him to the world. This is not unusual for me, I fall in love with people I make sure I’ll only meet in the archival world regularly. I have a larger-than-life crush on the untamed Leonor Fini, an even bigger one on Mina Loy. I want a tumultuous affair with the lasting breath of Helen Adam. I can’t get enough of Suzanne Van Damme and so often I wish to carry the children of Minnie Evans and Harue Koga, the ones they paint. This is who I am. I experience love within lives in-between.

I regularly compare my research to a dance: there’s me, in love almost always, opening and closing the gates of time and, hand in hand with my ghosts, escaping the tribunal of reason where archival gloves come off. Only the words I usually hide can explain how it feels to feel all these feels. With this painter, the one in Mexico (a name soon to be revealed, he/we are not quite ready) my dance is impassioned, untamed, confusing and restless. With others it feels like idiot glee, an encounter never not exhilarating. It feels like lightening. I’m attracted to the relentless glow of the artist’s personal galaxies, to the ways they’ve embalmed and encapsulated their mystique into works of art and music. I love you Ken Nordine. I don’t stop until I know it all, and I never really move on. I’ll never feel the skin they were once in but I can touch the hides they’ve concocted. “We’re involved!” says Mandella in 10 Things I Hate About You when she discusses a long gone Shakespeare. I believe her. Being involved with someone’s artistic legacy means, that for those interminable hot minutes, they’re all you can see.

Not just one partner on another plane, I’m constantly sat at a dinner party with many others. There’s a Mexican ghost, yes, and there’s a Jean. A Jean whose surname is regularly spelled and printed in two ways. (How arcane and supernatural my sweetheart!) Jean de Boschère, Jean de Bosschère (1878-1953.) A Jean I am also madly in love with. A Jean whose only dance move I’m privy to is the sudden and wonderful appearance of a book of his going for blindingly cheap on eBay. I don’t think he fancies me quite as much as I fancy him, but he definitely wants me to have a look.

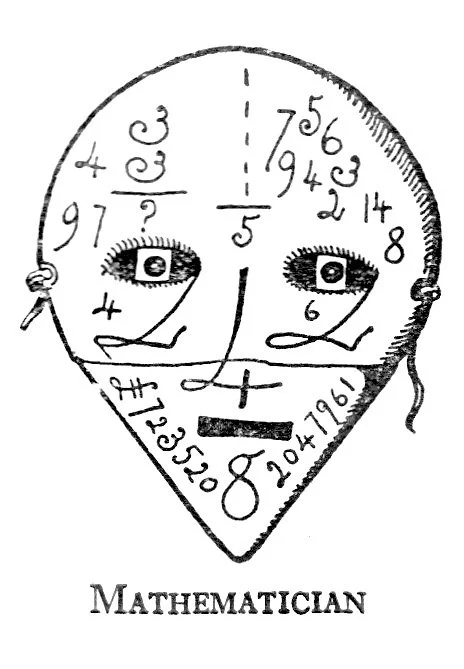

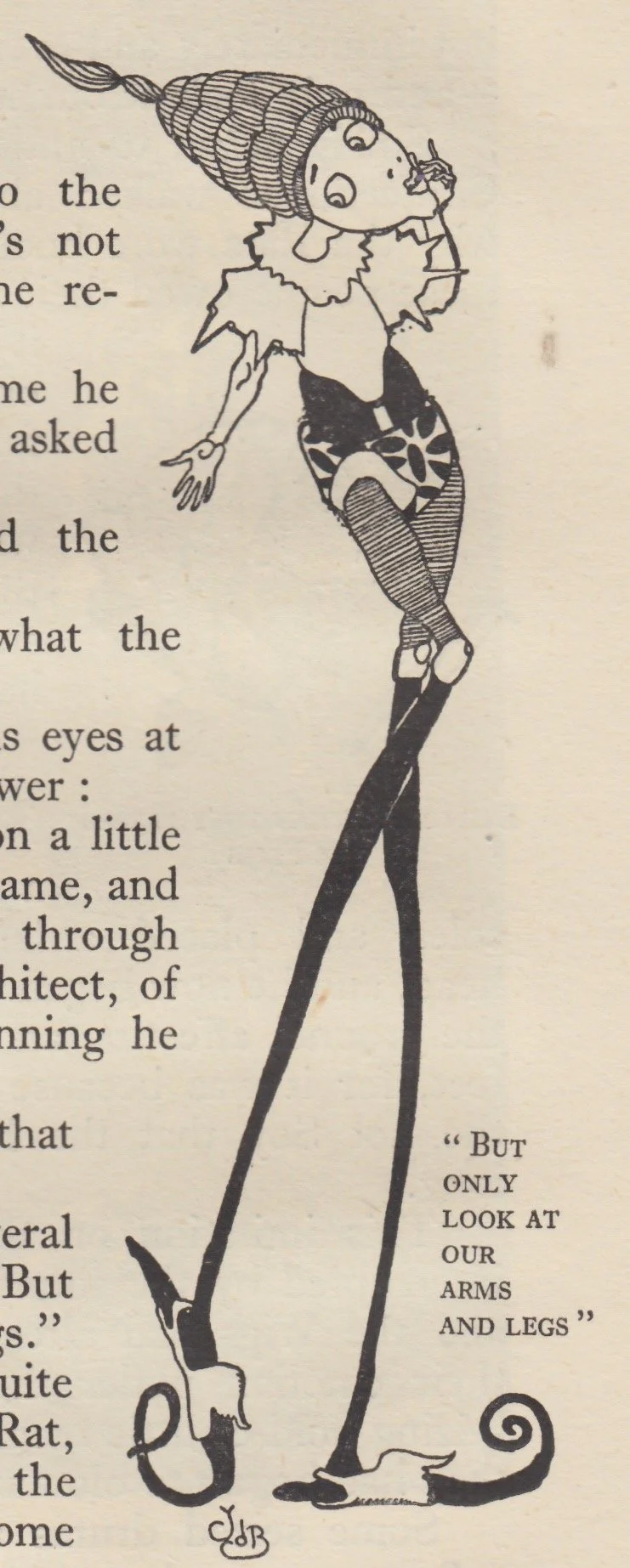

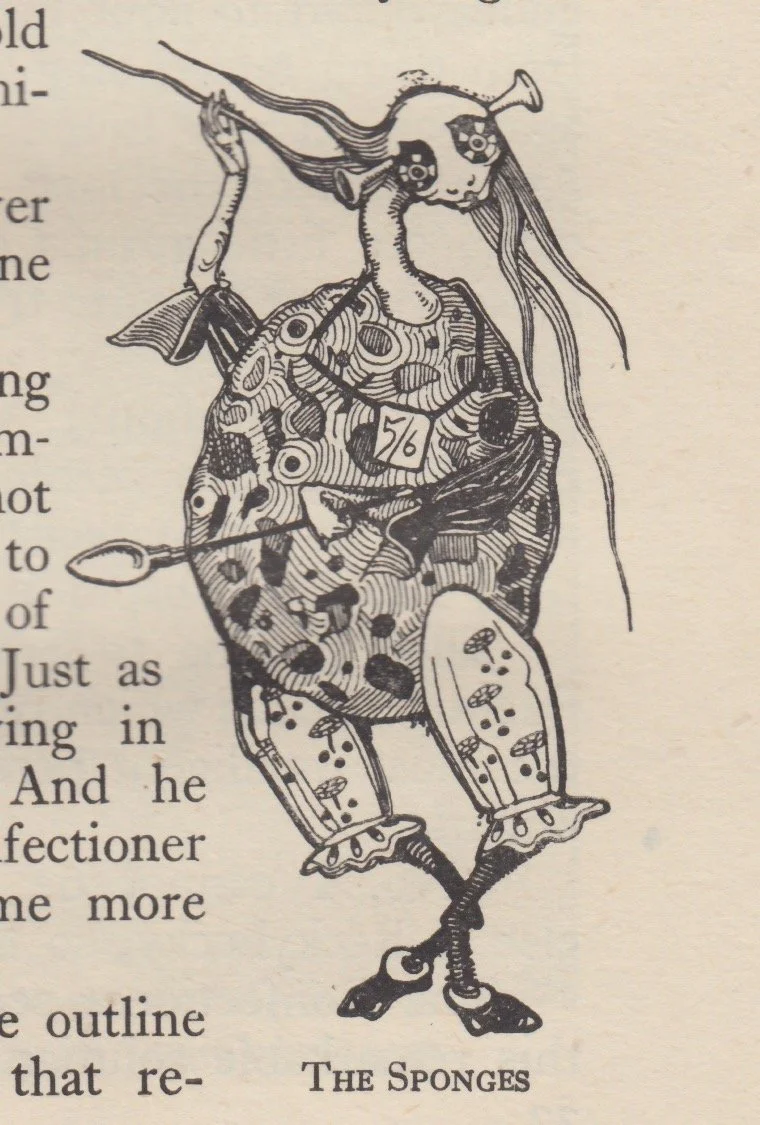

I first laid eyes on Jean de Boschère/Bosschère through the Internet Archive. In their signature generosity the gentle archivists working within this intangible vault had scanned the whole of Weird Islands for us (marvel here). There I was, sweaty hands, heart racing, toes curling. Who the fuck was this Jean, born 1878? I love him. I’d been bitten by Jean, died 1953. Alexia de Boschère/Bosschère was a pretty fantastic addition to the list of names I had inherited (like Alexia Moondog.) After a few years of finding versions of his books on eBay for very cheap (as I said, he liked that I was into him. Star sign: Cancer. Known for their devotion and attention.) I admired the fact that he’d been accused of Satanism after his first book was published. I loved his wild self-portraits. I was mystified by the fact he wrote so brilliantly in English too. I revel in the fact he probably would have found me so mind-numbingly boring. I love that so much of his brain leaks remained unpublished. There are pages and pages of him unturned and I want to be the one to turn them. Exaltation lies in my total inability to do that. Getting close to him through his words and wicked art was enough for a while, so infatuated was I with what bled from his mind.

What’s not to love about biographies, particularly if they showcase the people who unearth the people who the people forgot. Tales of a life are the most exciting kind of story to watch unravel: quilted, digestible voyeurism. Facts and moments bound together for us to walk with, some cumbersome dates sprinkled here and there and the possibility, always, to continue research outside of a book. Biographies and autobiographies are a reverse search into someone’s life, a sometimes biased retelling of experience lived. What I crave, particularly when I’m feeling a bit wild about someone, is a description of that person, in real time, by a friend, by family. By someone who has no idea what context they’ll be placed in, by a quick acquaintance who has yet to know what the subject of their attention will be leaving behind. As I open and close doors of the past, wanting to be with the ghosts, I yearn to know them, exactly as they were.

One Tuesday I stayed up until 2AM to win a very cheap copy of The World of Jean de Bosschère by Samuel Putnam. I won it because my Jean wanted me to understand a less fictionalised version of him (I am not deluded.) He wanted me to see past his colour palette in The Decameron. Look past the way he convinced me to holiday on his Weird Islands. Venture past the fact that he said delicious things like “but my mind stank of Juniper” or “love clothes the world in lace.” He was asking me to please stop idealising him just because he’d perfectly described what it felt and looked like to be a perverted historian in The Thin Long Arm of the Historian. In this newly acquired book, people were telling me who he was, how he was, to them. Friends were explaining, through dinners and conversation experienced, where Jean fit in a world he didn’t create while he lay in the ones he orchestrated, simultaneously. Jean de Boschère/Bosschère, my elusive Cancerian crush, had finally materialised. I idealise him, still.

Below are some passages from The World of Jean de Bosschère, edited by Samuel Putnam and written by the people with whom he shared his existing life. Jean, our Jean, finally untwines and you can join the cult as you fall in love with who he was.

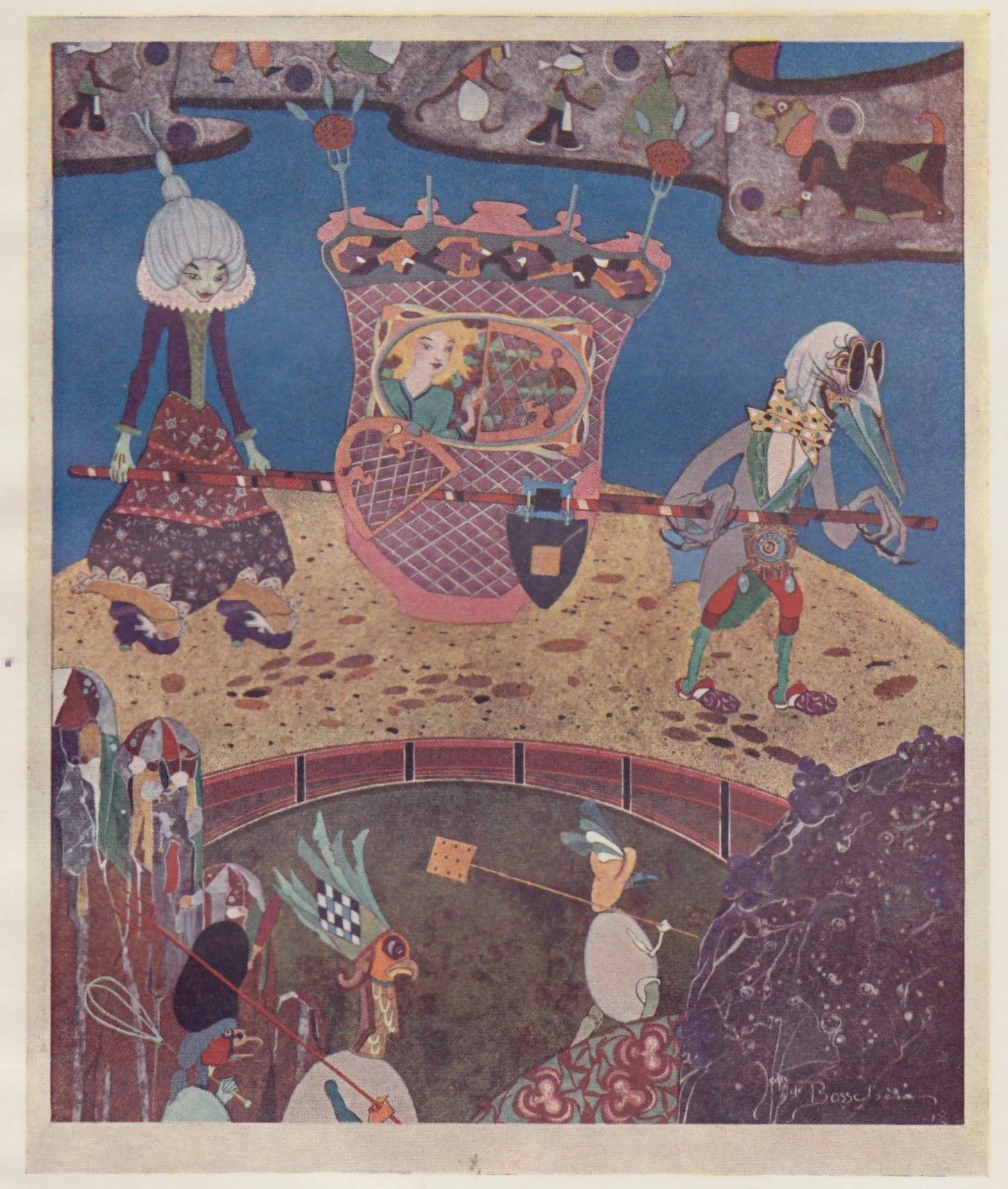

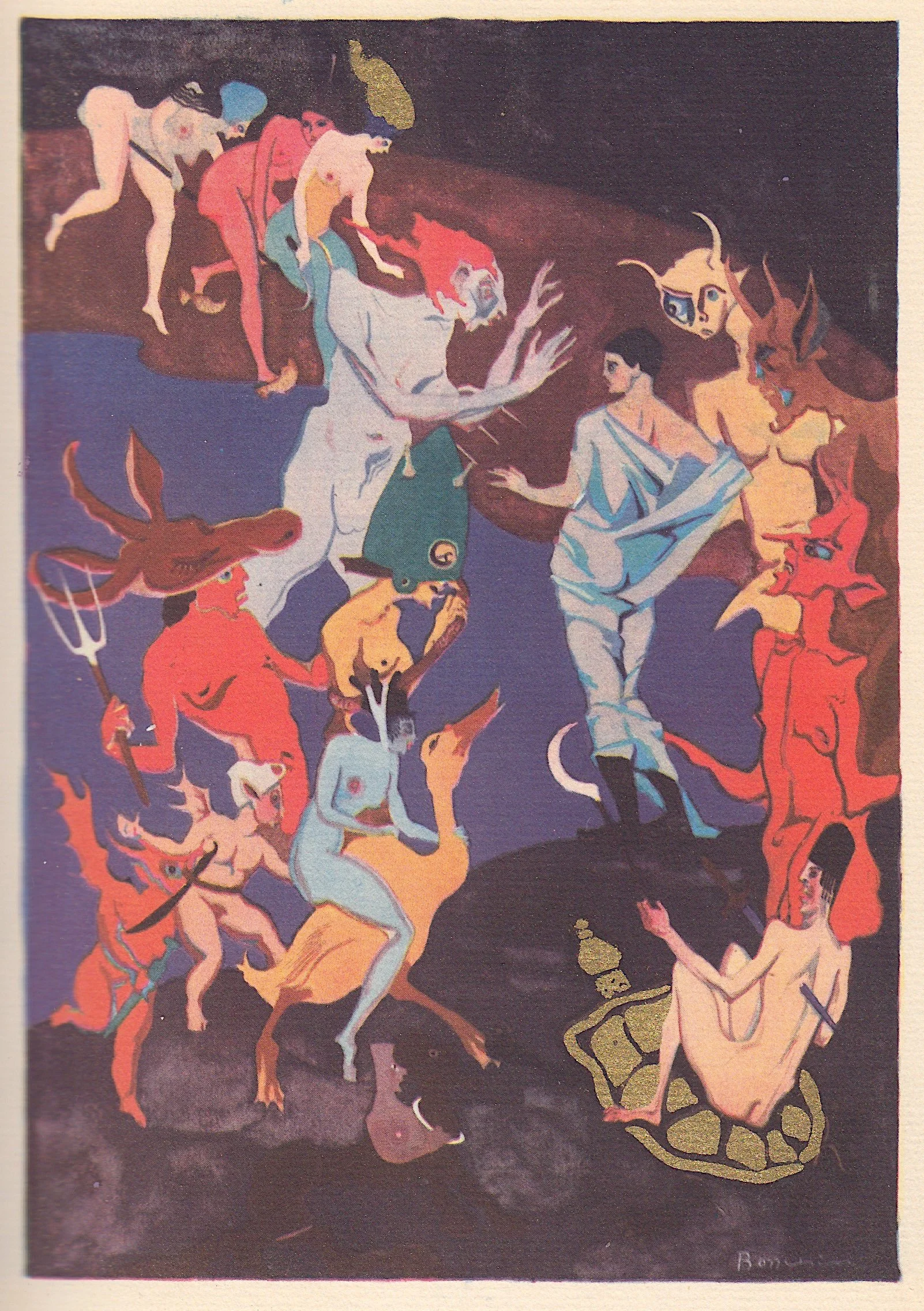

He is, it may be seen, a little intoxicated with colour. And his colours are seldom subdued; they are the lordly, the regal ones, the masters of the soul for good or ill. His are the primary and impinging hues: scarlet, green, black, purple, mauve and violet. And yet, into what a delicate world he transforms them, builds them up; a world of rose and grey, of “grey cloud and dew,” a world “white and yellow as honey,” a world of bronze dust and amber breezes, violet shadows and blue vases, a world of birds and flower-petals, of bees and serpents and perfumes, amid which femininely slender ephebi stalk their dog-drawn chariots and lead, or flee from, a “vie morose et lasse,” the gold of their robes serving as an “abracadabra against a pallid monotony,” their faces a “masque d’ange rose et pâle,” and their souls of polished crystal.

“But besides knowing what he wants, M. de Bosschère knows exactly how to do what he wants. He has the secrets of all the tricks of his art, a memory richly stored with visual images, and an inexhaustible inventiveness. You had only to run through the pages of one of his illustrated books to be convinced of this. There is never any flagging in the invention, never any tiredness; and the drawings are always more than a mere rendering in another medium of the suggestion of the text; they are in the real sense of the world and illustration, an illumination of the text by the light of another personality.”

“At school, I was so free with my wit that my mates used to called me: the diabolical soldier.”

“[...] The native of this undaily cosmos is the man of feeling, l’homme ardent, and he is ‘without past or future.’ The moment, the divine moment, suffices:

‘He possesses a whole instant above the abysses Like a juggler upright upon a knife.’

This is, essentially, Jean de Bosschère; the juggler above the abyss, a tight-rope-walker over the Niagara of infinity and eternity.”

“He comes bearing gifts, the gift of Magic: his is a magical world. No thesis, no sermon, no philosophy, no photography. He knows that “realism” is not reality, and that “reality” is not a matter of the optic nerve. He knows - how much does he know? The creator’s task is creation, the creation of a world. And creation, I submit, is essentially a magic process.”

“The pictorial Jean de Bosschère, who gets so much out of birds and flowers, likes birds and flowers around him in life, also. I do not think I have ever seen so many birds, in cages or without, congregating in one place before, as may be found in his tiny “self-contained” apartment. [...] Do not think that canaries and love-birds are his only furnishings. There are rare books and rare bijoux, paintings and easels and etching-presses, a reading corner, dining-table, and a divan. Here, again, Bosschère the man and Bosschère the artist are inseparable: he makes, he recognises with no division. You see the real Bosschère, perhaps, when he begins taking down his books, one by one and starts caressing their bindings.”

“Within the cool shade of his house is another world, the demiurge’s expansive workshop; for the whole house is that. Downstairs and up, the walls are covered with Bosschère, Bosschère the painter, rather than the illustrator; they are fairly crawling with that weird submarine cosmos. Bosschère recently presented me with an etching. It bears the title: “L’Écrevisse Pense à l’Homme et à la Femme” ("The Crayfish Thinks of Man and Womankind.) Bosschère’s world might, not inaptly, be defined as a world of thinking crayfishes, and the walls about us groan with those “thoughts.” [...] It would be insincere to pretend that he prefers any other world than that of his own creation.”

“Some four years ago he acquired an estate of proportions at Vulaines-sur-Seine. [...] Unexpectedly, through the tall and timeless trees that line the road, we catch sight of a high iron grating, and behind it, embedded in a sea of colour, a symphony in yellow and black that is Jean de Bosschère’s house. That ‘sea of colour’ is, literally, that. It is so blinding, in the season of bloom, that one does not make out at first the individual beds and clusters of bright-hued flowers, red predominating - red and black and yellow - once more, those lordly ones, the masters of the soul. It is all out of a Bosschère picture. It is a Bosschère picture. [...] The neighbours threw up their hands in horror when that colour-scheme for the house was proposed: they could not visualise it, save as an undertaker’s dwelling. They now peep, through the grating, at the strutting, resplendent-winged peacocks, the pheasants and the rest of the ornithological collection. This collection is already quite a large one, and Bosschère plans to make it larger yet, by screening in the whole of the small valley behind the house and making of it one huge flying cage.’

“The short of it is, Bosschère, wherever he may happen to be, must create a picture, a world that is a picture, a picture that is a world. He must impress himself upon any universe that he, conceivably, could inhabit, must mould that universe to his own likeness; his is the spirit of the true demiurge.”

below are additional pages of "The City Curious" by Jean de Bosschère, 'retold by F. Tennyson Jesse' (William Heinemann, 1920) // "The Decameron on Giovanni Boccaccio Vol.I,II" Translated by Richard Aldington, illustrations by Jean de Bosschère ( G.P Putnam's Sons, 1930) // "The Golden Asse of Lucius Apuleius" translated out of latin by William Adlington and illustrated by Jean de Bosschère (Murray's Book Sales, 1932)

words: Alexia Marmara