In conversation: Micaela Brinsley

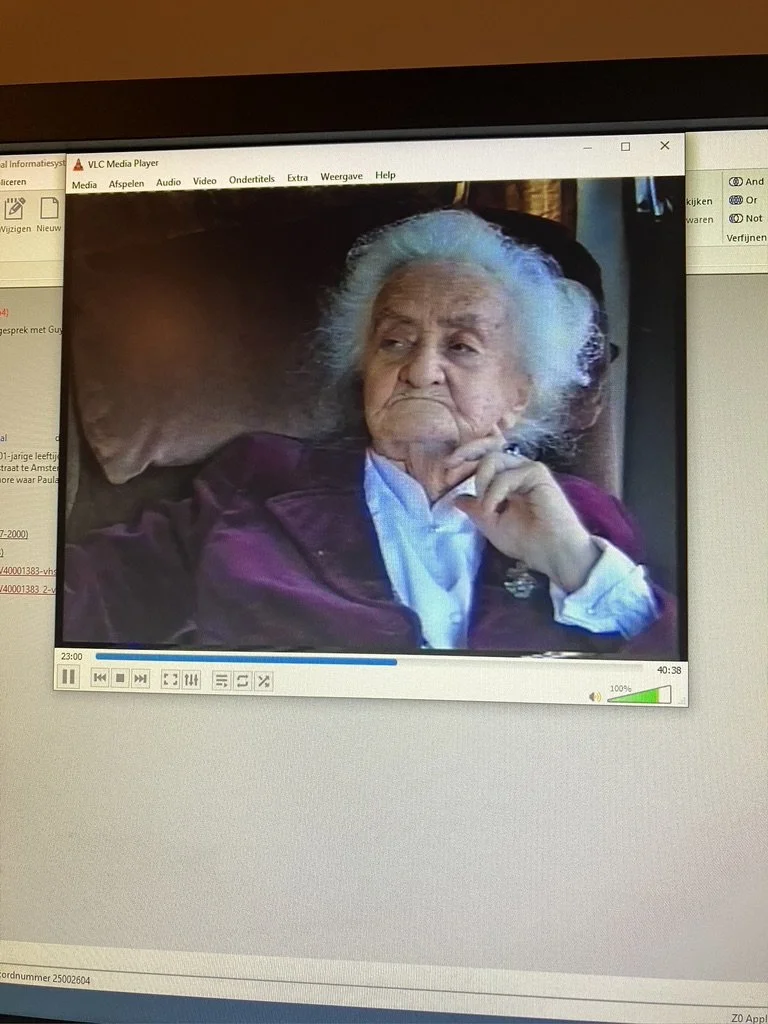

A discussion with Micaela Brinsley in which we touch upon being stained by our separate research projects and why archive fever helped us become… us. Where I remain a little private about a budding project, Micaela reckons with being consumed by a ghost and how memory’s discoloration has continually affected her work.

In addition to her generous and graceful insight, Micaela wrote a piece for Amurmur.

*The following essay contains subjects that may be upsetting or triggering for some readers. Please take care while reading. In Suspension of the Before To After

Micaela Brinsley

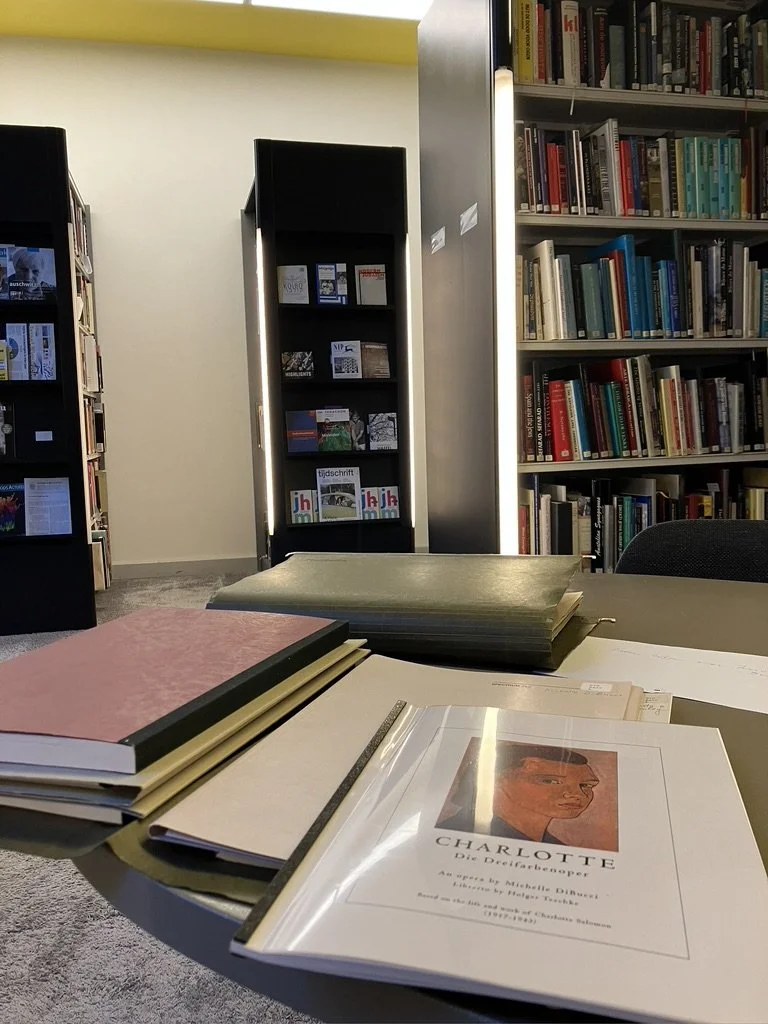

As if a part of me exists within the mitochondria of a dream. I'm somehow suspended in a snow globe, floating. When I look back at my time in Amsterdam, researching Charlotte Salomon’s archive, its moment exists in me as a kind of stillness.

As it was happening, I felt as if I was changing from second to second. Living on the edge of knowing myself, it's the same feeling as licking frosting off of the tip of a sharpened knife. There's a way in which the thrill of entering into a kind of monastic bubble of the self, for me, it surpassed any previous sensation of joy or laughter, or even of pain or suffering. For that moment in 2022, I was entirely and utterly dedicated to the study of something that I will never fully know, that I wanted to get closer to and closer to, despite the impossibility of satisfying my desire. Every piece of information I learned felt as if I found a new way of opening a door, as I became increasingly sensitive to this feeling of being so fully attuned to one thing, to one sensation—the sensation of being autonomous.

Like being in a state of constant ecstasy. The only reason why it could be sustained over the course of some months was because I knew that I had walked in from a specific door on a certain day, at a certain moment, and that I would also be exiting from another door at a different moment, with a date that had been selected ahead of time. That gave me permission to surrender to the time in-between. I had an entry point, I had an exit, so I was able to surrender fully to whatever came my way within the archive. There, I felt myself becoming porous to a world that I was choosing to inhabit.

Not my world, but the world of Charlotte Salomon, opened itself before me in fragments.

For the first time in my life, I felt as if I was someone that I could choose to be. Previously, my upbringing was tinged with a sense of dislocation, as if I had been almost created in the proper shape as a fetus before my birth, but something in me was missing. That the code had been inputted almost, almost correctly. Perhaps I felt like a permanent phantom limb, an extension of a body with a too-long gestational period (I was supposed to be a Leo, but was born a Virgo). Because I had this sense that there was something off about me, I constantly felt as if my existence was contingent on responding “correctly” to whatever came my way, rather than wandering through a sequence of events that I was choosing for myself. The self-imposed surrender into the archival world of another person became the method by which I could entirely run away from my previous life, which, as I spent more and more time in the archives, felt less and less real.

Previously, I invested all of my critical, emotional, and sensorial attention into succeeding in the world of theater. That heightened awareness of every moment and my conviction that without my full attention, opportunities would slip away from me—once I let go of all of it, this temporary moment in time underground taught me of how much attention I was capable of giving to my own life. I was now capable of giving attention to what it felt like to walk, by myself, across a moonlit bridge at night. The taste of apple pie with the lick of coffee, right behind. The touch of a finger against my thigh. The smell of the train when I walked through its doors on my way back to the small room I was renting, slightly outside of the city limits of Amsterdam. Every moment, every action, was now tinged with 360 consciousness, as opposed to the disassociation that had previously marked my days. In other words, before my time in the archives, all of my energy had been directed to succeeding at something in my life, rather than living all of it for myself.

I had never done anything like this.

Every way I rebelled previously, was in secret.

From others, and even in some ways, from myself.

So this time with only Charlotte Salomon’s memory for company felt like an escape, a fantasy, more real than any of my life had felt up until that moment—like freedom. I sliced through all of the layers of myself to reach the heart of me: a nerve. A quivering need whose language I didn’t know. How to describe it? I couldn’t then. I mostly can’t, now. But then, for the first time in my life, I didn’t feel the need to justify my life to anyone else. Or maybe, I just needed to give myself permission to listen to me.

But for those months, I barely spoke a word.

To anyone.

Haunted Amsterdam like a ghost myself.

I knew this state wasn’t sustainable—I’d eventually need community, stability, a sense of continuity. Perhaps because that time was so disconnected from language, I’ve struggled to write about it since. Now that I’m in the fallout of that moment, I have a very tentative relationship with getting close to it again. I think those kinds of moments of catharsis only work when it’s a temporary state of mind, and not thought of in the context of any sort of permanence.

The story of life of Leben? oder Theater? (Life? Or Theater?) goes something like this.

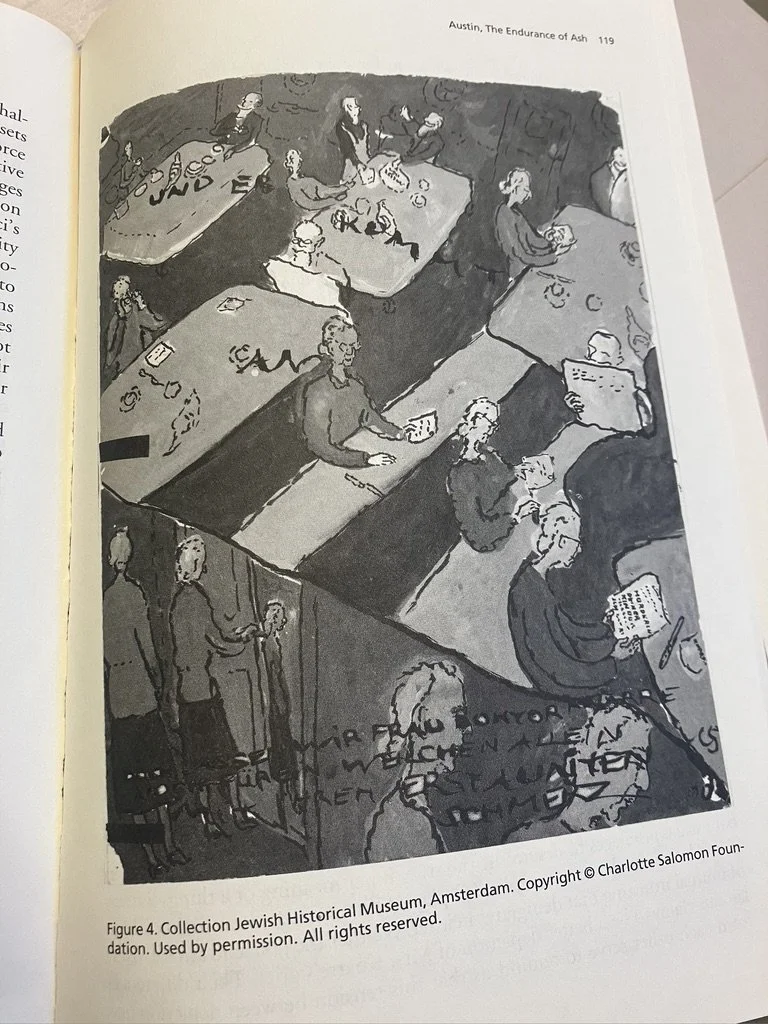

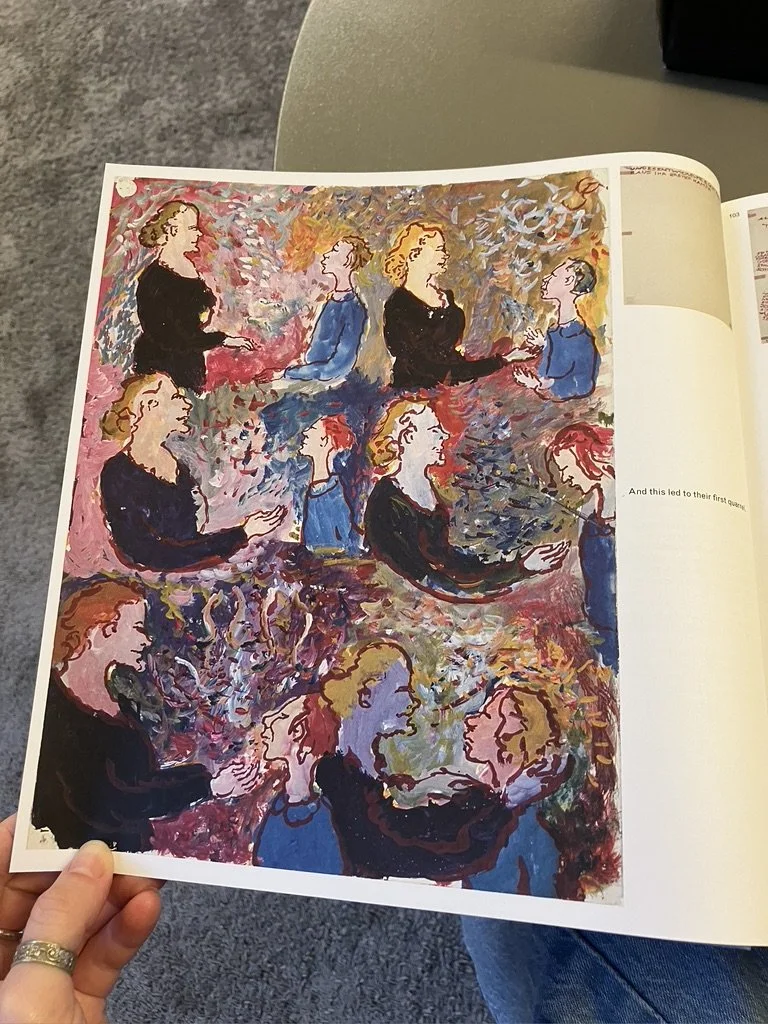

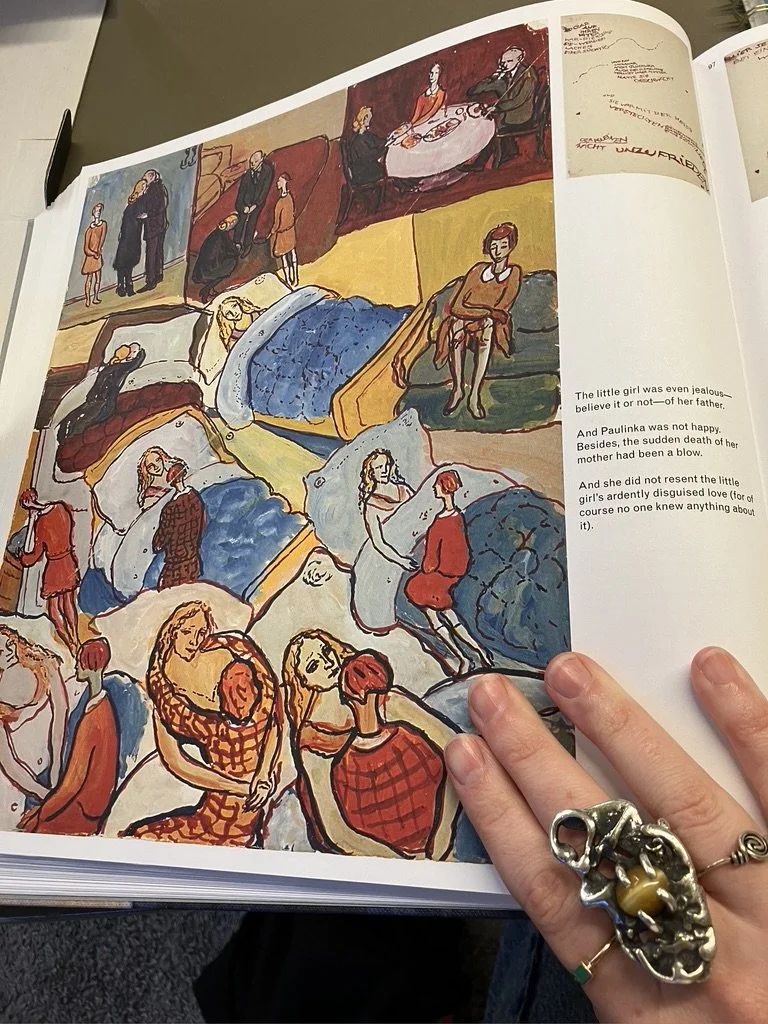

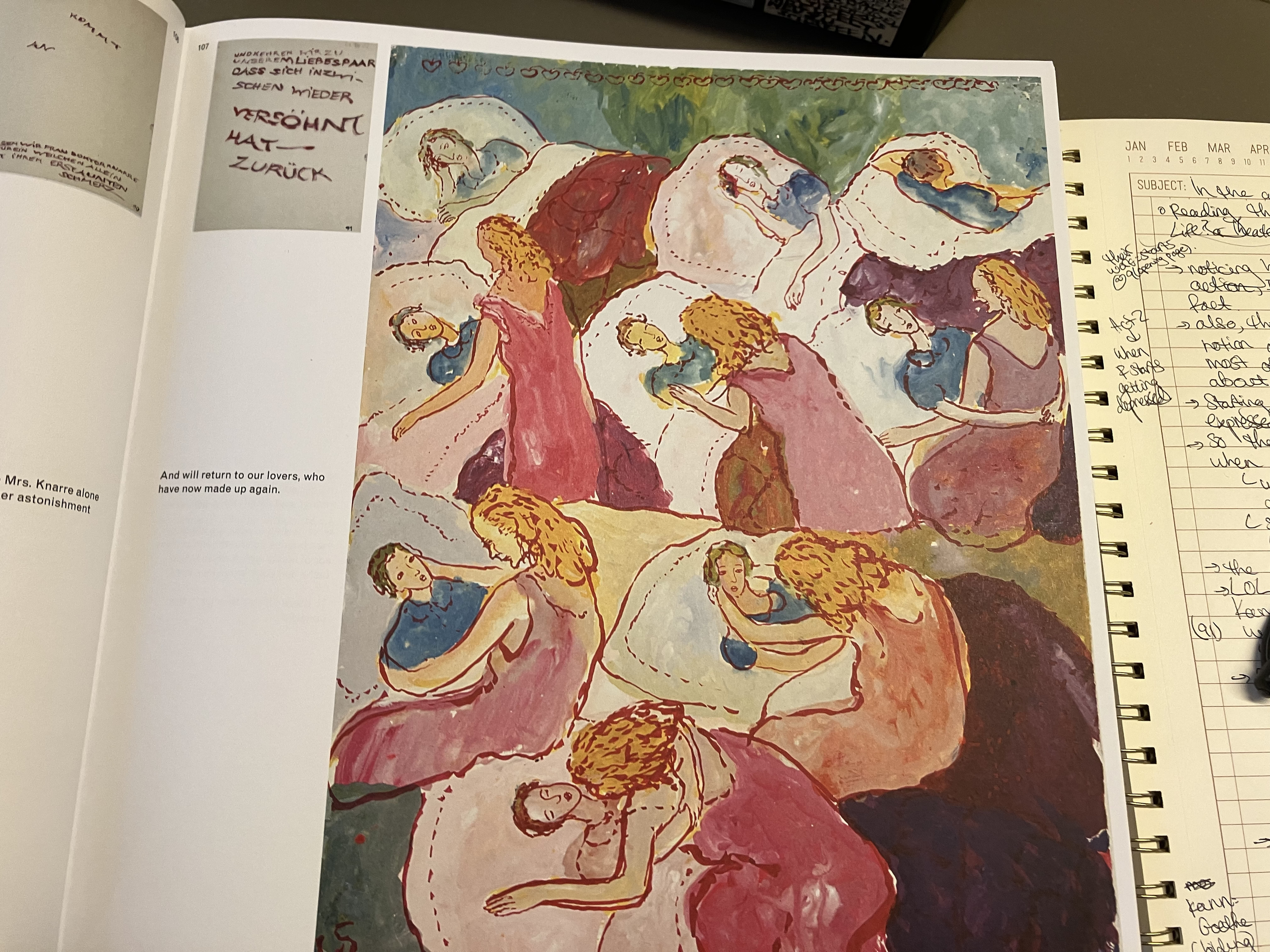

[A girl named Charlotte commits suicide by jumping into a lake. Her body is recovered and her family finds her. Her older sister, Franziska, decides to become a nurse, to help those who might also be struggling. She meets a doctor in a ward. They fall in love. His name is Albert. They get married. She has a baby. They name the baby Charlotte, after her little sister. Franziska is a pianist, but she is bored and depressed. Her mind is at war with herself. She tries to find beauty in her life. She tries to commit suicide by jumping out of a window. She fails. She survives. After some time in bed, everyone thinks she's better. She successfully commits suicide in her second attempt. Her daughter named Charlotte, by this point a young child, is raised without knowing the real reason for her mother’s death. During this period of mourning, Charlotte’s grandmother, Marianne, has flashbacks to her own youth, her family, the raising of her two daughters, to writing. Marianne is a poet. After her daughters are born, her brother commits suicide. There is a suggestion that he might have been gay, though it is not confirmed. Marianne moves forward in time to the mourning of the death of her first daughter, then of her second daughter. We return to the present day when her granddaughter, Charlotte, is a child. Together, they go on trips to different countries across Europe: to Italy, to Switzerland, back to Germany. In the meantime, Charlotte's father has met an opera singer, Paulinka. Now, we go down a flashback of her life, from her childhood, to her love for her father, her attachment to a singing teacher who sees something in her. Her father dies. This teacher decides to mentor her, encouraging her to abandon her Jewish-sounding last name for another. A second father, with whom studies to become an opera singer. She travels from theater to theater, singing for him. When he dies too, she feels as if there’s no one to sing for. She sings in mourning, still traveling from theater to theater. She meets a doctor. He happens to have a child named Charlotte. She marries him because she thinks, why not? Someone to care for, someone who cares for her. We’re now back in the present. Charlotte is enamored with her stepmother. She tracks her eyes, the movement of her mouth, the shape of her arms, the insides of her elbows, the sides of her neck, the way her back moves when she walks, the smoothness of her legs, the sound of her voice, her voice. Over and over again, Charlotte feels as if Paulinka’s sound was in her bloodstream all of her life, and only now is she feeling the movement of her own blood. Just as World War II begins, a man enters their life, a singing teacher, an amateur theorist named Amadeus. The Nazi party comes to power. Paulinka starts taking lessons with Amadeus. Nazis start visiting Albert at work. Charlotte is jealous of Paulinka’s attention on Alfred. The Gestapo visit performances where Paulinka is singing, tracking her movements across the stage. Amadeus believes that in order to access one’s true artistic voice, you must die first, then become reborn. He writes a book about this, we follow him as he writes it. He has no idea what he’s talking about, though he did almost die in World War I. Paulinka is enamored of him. Charlotte is jealous. Of him, of her, of everyone—confused. She is a teenager, the only child in this world. Always off to the side, as if irrelevant to its movement. She’s always made drawings. She applies to an arts academy. She is rejected. She studies drawing with a personal tutor. The next year, she applies to the same arts academy. She is admitted as the only Jewish student enrolled in the school, as she is deemed asexual and harmless by the admissions committee. What they don’t know. Her stepmother, at this point, is on the verge of a full-blown physical affair. Emotionally, she’s already there. Charlotte starts meeting Amadeus in secret. Soon, she is having sex with him, potentially because she knows Paulinka will never follow through with an affair, potentially because Charlotte wants to see what it’s like. Potentially also because she knows Amadeus will want to as a way of feeling closer to Paulinka. In any event, as this is all happening, Charlotte is also in love with her classmate named Barbara. Charlotte, while excited by Amadeus’ attention, does not enjoy sex with him. There’s a darkness underneath those paintings, the same darkness in those when her mother and her aunt were young and they were running away from being assaulted by their father. It becomes clear that the legacy in this family is that men assault women, who then wound themselves. This pattern continues and continues. Once Charlotte’s father can’t practice medicine in the open anymore and her stepmother, as an opera singer, can’t arrange for illegal papers to be made for refugees to leave Germany under the guise of being musicians for an orchestra pit anymore, Charlotte realizes maybe it’s time for her to leave Germany. She leaves Berlin for Nice, for the south of France. She will never see Albert, Paulinka, or Amadeus again. She arrives where her grandparents are living as refugees by the sea. Out of contact with her father. Out of contact with her stepmother. Out of contact with the man who… did she love him? Did she feel compelled by him? Did she want something he had? Did she get it? It’s hard to say, though she misses something about him. Her grandparents are confused by her reticence. Her grandmother starts to become increasingly depressed and sits by the radio every day. As the Nazis advance across Europe, Marianne feels increasingly claustrophobic, thinking about the poetry she wanted to publish during her lifetime. She is full of regret. She tries to hang herself. She fails. Charlotte, completely distressed, tries to remind her of the pleasures of being alive. Reminds her of her poetry. Reminds her that even now, Marianne can write. Charlotte, by Marianne’s bedside, tries to make her want to live again, to talk with her about what life could be. She tries. It seems to work for a while. But her grandmother successfully jumps out of a window and kills herself. Charlotte is distraught. Her grandfather seems relatively unbothered. By this point in the story, it’s clear that something is deeply wrong with him. He also confesses that her mother, like her grandmother and aunt, committed suicide when Charlotte was a child. He tells Charlotte that she is next. Charlotte repeatedly refuses his attempts to sleep with her. They are eventually taken by the Gestapo to a concentration camp. On their way there, her grandfather tries to sleep with her again. She manages to refuse. After some time at the concentration camp, by some miracle, they both escape. They land back in a house in Nice with her grandfather, who continues to try to get her to sleep with him. A letter from Albert and Paulinka arrives, detailing their joy at Charlotte and her grandfather’s survival of the concentration camp. Determined to find some way of surviving the hell she’s living in, Charlotte decides to paint. To isolate herself in her room above the sea and paint the story of her entire life. Images she creates out of her own memories and the shards of stories she’s been told, stories she’s suspected, ones she wants to relive, to reinterpret, to reinvent on paper. She narrates sequences she can’t confirm, with the ghosts of memory by her side, surrounded by fear and pain and depression and confusion, truth and fiction, life and theater. The piece ends at the moment of its creation, as she paints by the sea with the face of her mother lightly sketched in the blue expanse in front of her body.]

*Some time after the creation of Leben? oder Theater? Charlotte Salomon marries a man she meets in France. She registers her marriage in the public record. The Gestapo learn of her existence and arrest her while she’s five months pregnant, along with her husband. They are both taken to Auschwitz. In the records from the concentration camp, she is listed as a draftsperson. She was likely murdered instantly when she arrived.

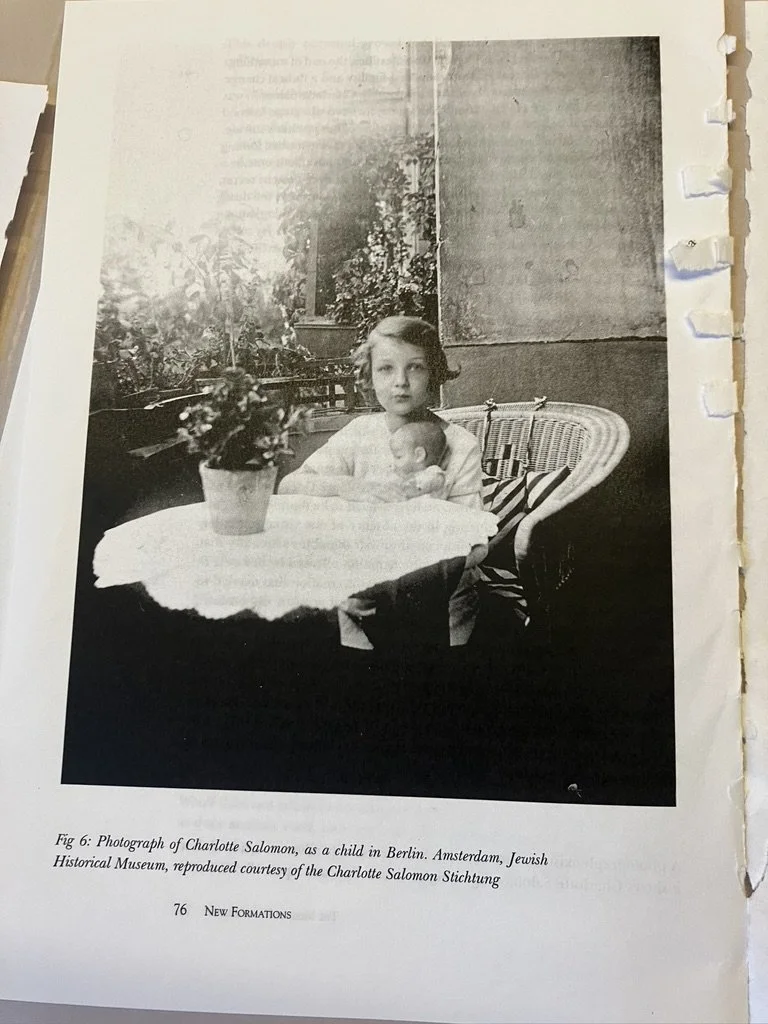

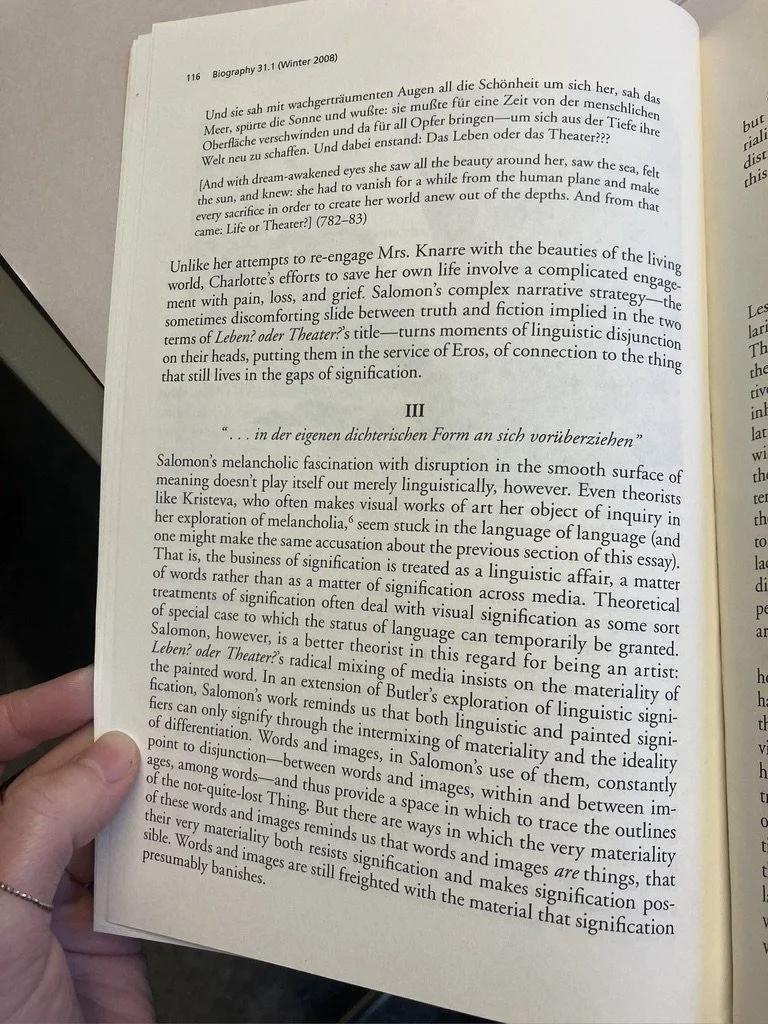

Griselda Pollock The missing photograph: Charlotte Salomon Life? or Theatre? as the encounter with maternal loss (New Formations, Volume 2009 Number 67)

Leben? oder Theater? is the rendering of a life within the context of its feeling. The result of a revelation, the next step following the confirmation of a long-felt sense that something isn’t right about how the world is arranged. It changes everything, everything. The silent exchange of unspoken secrets no longer feels sufficient and some new evidence must be left. Something that refutes the framing of the before.

Only occasionally does the theater surrounding our everyday life crash entirely to the floor and we’re left, alone, looking around an empty space and a brick wall. What is present, when artifice falls? A soul, naked and raw. Paint seems natural as a conversation partner for this fragile thing. A surface upon which to draw new images, new feelings, a location for it to express a new texture of being, of seeing, of being seen. Paint may feel like the only material upon which an experience that can’t be summed in words, be placed. What it means to be alive isn’t taught in school. Rarely is anyone honest, really, when they give advice about how to find it. If no one is around to ask questions and no one is around to answer any either, to make art seems like a practical way to figure out how to move forward.

Many of us are gaslit into our realities by people who mean well, some who don’t—many who read history as a collection of numbers arranged around some gravestones. What came before all of our lives can’t be arranged around a simple plot line with an inciting incident, rising actions, a climax, and a resolution—except the moments we bend an experience within the framework of it. This work, Leben? oder Theater? rejects even that supposition—that art must follow a trajectory familiar with its audience. Its audience, after all, was the mind of a person convincing herself to stay alive. And it worked, it did. She broke the curse of the women in her family before her, by not killing herself. This hybrid work of paint and gouache, Leben? oder Theater? resists simple categorization. It is a testament to the triumph that arrives when life is rendered under the auspices of instinct. When art is made after looking life right in the eyes, a soul is revealed somehow, free in movement to its own rhythm.

The likelihood of any of us being born is so infinitesimal, it’s a miracle that any of us get to be here. It’s all a result of the luck of the draw—a second of a difference could’ve meant that someone else had the chance instead. Works like Leben? oder Theater? insist that who we are is made up of the way we answer the question need asks of us in crucial moments when, at a crossroads, we decide to explore our life on our own terms.

Micaela Brinsley is a Tokyo-born writer, editor, and researcher of art and performance. Her debut pamphlet, Forward, was recently published by Cutt Press. Her prose can be found in Tenement Press, Asymptote, Tique, Horizon Magazine, Minor Literature[s], and other publications. She is a contributing writer for the journal A Women's Thing, where she writes essays about surrealist and abstract artists, as well as the co-editor-in-chief of the arts and literary magazine, La Piccioletta Barca. She is currently based in Buenos Aires. All images courtesy of Micaela Brinsley@mic_brinsley